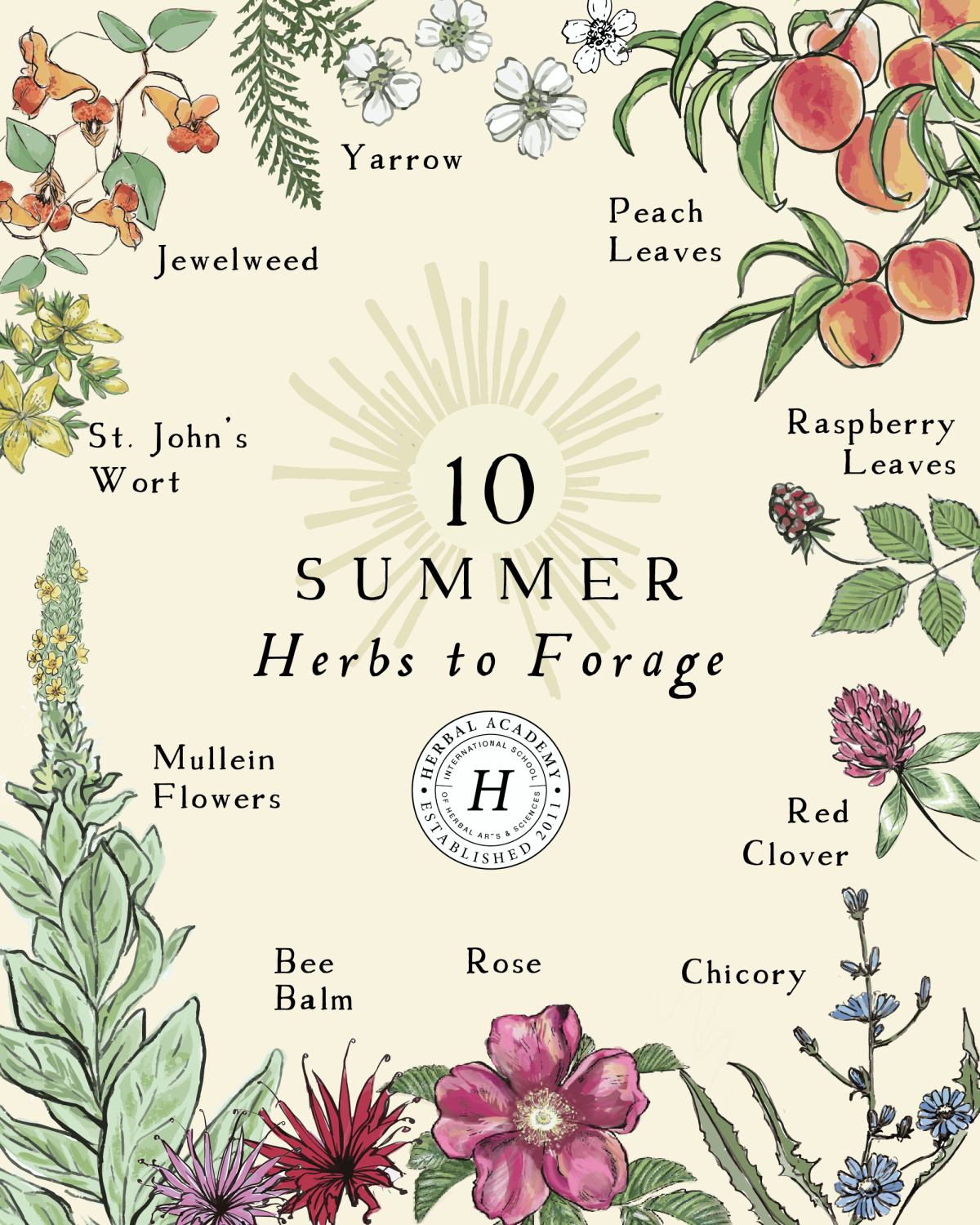

10 Summer Herbs to Forage This Year

The “Dog Days” of summer are upon us in the South. The dogs and cats are lazy, the snakes are more prone to bite, the gnats, flies, and mosquitoes are more bothersome than normal, and the poison ivy is thriving. Thankfully, it isn’t all bad. These slow, hot days bring more time for family gatherings, playing in the creek, sitting on the porch swing watching the sun go down behind the mountains, and an abundance of summer herbs to forage.

Today, I’d like to share with you 9 of my favorite summer herbs to forage. These herbs are abundant here in the South this time of the year, and depending on where you live, they may be blooming in your backyard, too!

Foraging Tips To Get You Started

Before I share some of my favorite summer herbs to forage with you, let me quickly cover some basic foraging (wildcrafting) tips to keep in mind.

First, always properly identify your plants. There are some great foraging field guides out there that can help you identify plants as well as some Facebook groups to help you with identification (I’ve include a couple suggestions here), but if you have a friend who can help you positively identify the plants you’ve found in person, that would be best.

Next, be sure to know if the herb you’re planning to harvest is at risk of becoming endangered. The United Plant Savers is an organization that works to protect at-risk plants so we can have them around for future generations. Let’s be responsible with the gifts we’re given! If the plant is on the to-watch or at-risk list, try to find a cultivated source to use instead of harvesting it from the wild.

Be sure to harvest plants growing in clean soil. That means to stay away from roadsides, places where chemicals or animal feces run off or are dumped, and areas close to city buildings and businesses. These places can be contaminated with chemicals and other toxins you don’t want on your plants. Also, be sure you have permission to harvest if you are on private property.

Lastly, don’t harvest all of the plant in one given area. The forager’s rule of thumb is to only harvest ⅓ of the plant growing in any given area. This is to ensure that there’s more for other foragers, for animals that survive on plants, and for the plant’s life cycle to continue.

10 Herbs to Forage in Summer

Rose Buds & Petals (Rose spp.)

Rose is a common herb to forage during summer, and where I live, bright pink roses can be seen growing freely on the sloped banks of the back roads as well as in gardens and flower beds near homes. And if you’re lucky, you might even stumble across a wild rose bush in the mountains somewhere!

Rose varieties consist of one or more layers of 5 separate petals and a minimum of 5 sepals. All varieties of rose have multiple stamens, and the leaves are often oval shaped and serrated around the edges. Rose leaves are alternate and vary from simple to trifoliate, palmate, or pinnate among varieties (Elpel, 2013).

Many varieties of rose are edible and can be used in herbal products. Just make sure the buds and petals you’re harvesting haven’t been sprayed with chemicals before collecting them.

Rose buds can be harvested while they are still closed but the petals are slightly loose. To harvest rose buds, use sharp shears or scissors to snip the buds from the plant. Rose petals can be harvested anytime they’re in full-bloom. To harvest the petals, gently pull to remove them, but be sure to watch for bees! Rose buds and petals are typically dried, but they can be used fresh if you wish.

Herbalist Matthew Wood suggests using rose during acute inflammatory conditions of the respiratory tract or to bring cooling relief to hot conditions of the digestive tract (Wood, 2008). According to herbalist Kiva Rose Hardin (2007), rose can also be used to calm and cool the skin, lift the mood, and soothe fragile emotions. It can also help bring balance to an overactive immune systems and “purify” the blood (Hardin, 2007). Roses have astringent properties and are suitable for most all skin issues (“Rose,” n.d.).

Red Raspberry Leaves (Rubus spp.)

Berries aside, the leaves of the red raspberry plant is another common herb to forage during summer.

Red raspberry plants have white flowers—each with 5 separate petals and 5 sepals, as well as ovate shaped leaves with serrated margins. Leaves are typically pinnate compound leaves arranged in an alternate pattern. Leaves are commonly green on top with a white/grey coloring on the bottom (“Red Raspberry,” n.d.).

Red raspberry leaves are to be harvested after fruiting has begun. To harvest red raspberry leaves, simply snip leaves with sharp shears or scissors on a dry day. The leaves can be a little sticky or prickly feeling so feel free to wear gloves if you wish. The leaves can be used fresh, but are more commonly dried in teas, syrups, and tinctures.

Red raspberry leaf is an astringent herb and is often used to tighten and tone relaxed tissues, specifically those in the digestive and reproductive organs (Wood, 2009). Speaking of the reproductive organs, David Hoffmann, in his book Medical Herbalism, states that red raspberry leaves’s astringent, tonic, and nutritive properties aid in strengthening the uterus and pelvic muscles, helping to discourage miscarriage, shorten labor, ease labor pains, and speed postpartum recovery (Hoffmann, 2003).

Mullein Flower (Verbascum thapsus)

Mullein flowers are one thing I’m sure to forage for each year. As summer progresses, I keep an eye on the tall green stalks of mullein for those first bright yellow flowers to start popping out. A week or so after the first flowers appear, mullein flowers are ready to harvest.

Mullein plants can reach anywhere from 6-8 feet tall and have a rosette of oblong, hairy leaves arranged in a spiral around the base of the plant. Leaves can measure up to 12 inches long and branch out from the stalk in an alternating pattern ending with the flower spike at the top. Flower spikes are typically a foot long, and produce small, yellow flowers in mid- to late summer (Grieve, 1971). Flowers have 5 petals that unite at the base to form a short tube, 5 united sepals, and 4-5 stamens of equal length (Elpel, 2013).

Mullein flowers are typically harvested as they begin to bud and open. To harvest, gently pull the mullein stalk down to your level, being careful not to break it, and pull individual buds and flowers from the flower spike. Watch out for bees, and don’t be surprised if you have sticky fingers after harvesting the flowers due to the resin content!

Mullein flowers are typically used to soothe and calm painful inflammation in and out of the body (“Mullein,” n.d.). They are also used for both mild and strong relaxant effects that vary from individual to individual when taken in tincture form, according to herbalist jim mcdonald (mcdonald, n.d.). Mullein flowers are usually infused into oil after a brief period of wilting and must be made fresh yearly. Herbalist Maud Grieve states that fresh mullein oil can be used to discourage bacterial growth, and a 2003 study published in Pediatrics journal supports this finding as well (Sarrell et al., 2003). Mullein flowers can be dried and added to teas or used fresh in tinctures as well.

Peach Leaves (Prunus persica, Amygdalis persica (Linn.). Persica vulgaris Null.)

Peach is an herb I’m new to using, but it’s another herb that is commonly foraged for during the summer months—the leaves in particular

There are several varieties of peach, but most all are medium sized trees with 4 inch long, lance shaped, finely serrated leaves. Blossoms grow in groups of 2 or more at the end of last year’s branches and are pink in color with 5 petals, 5 sepals, and many stamen (as it’s a member of the rose family). Blossoms turn into fruit with thin skin, juicy flesh, and seed encased in a wrinkled pit (“Peach,” n.d.).

Peach leaves are harvested after the fruit has ripened on the tree. Heavily harvest peach leaves by clipping those free of blemishes with a pair of sharp scissors. Peach leaves can be used fresh or dried in poultices, teas, syrups, and tinctures.

Matthew Wood suggests using peach leaves to cool and moisten hot, dry conditions like those that can present themselves during allergies or autoimmune issues. He also recommends it for skin eruptions, hot digestive and respiratory conditions, and to help cool the body during menopause. It’s also an excellent herb for children and sensitive individuals (Wood, 2008). Kiva Rose suggests using peach for to aid an upset stomach and nausea anytime there are signs of excess heat, to help with adrenal health, to relieve hot, swollen bug bites, and to soothe the nervous system as it has an almost sedative-like effect that varies from person to person (Hardin, 2009).

Chicory Flowers & Root (Cichorium intybus)

Chicory and its beautiful blue flowers can be seen growing all along the roadsides here in the South during the summer months, and it’s another great summer herb to forage for at this time of the year.

Chicory, like its cousin dandelion, grows from a long taproot anywhere from 2-3 feet in height with lateral stems that branch out from the main stem at sharp angles. Lower leaves at the base of the plant are larger in size, covered with hairs, coarsely toothed, and branch off at right angles where the leaves on the upper portion of the plant are smaller, less divided, and their base is connected to the stem (Grieve, 1971). Chicory stems contain white milky juice, and the delicate blue flowers of the chicory plant branch out where stem and leaf meet. The distinguishing factor of this Aster family subgroup is that the ray flowers have mostly parallel edges, like a strap, as opposed to tapered edges like other flower petals. Individual petals overlap to the center of the flower (Elpel, 2013). You might be interested to know that chicory flowers open in the morning and close by mid-afternoon.

To harvest chicory root, use a root digging tool (a shovel will work, too) to loosen the soil around the root. Gently lift the plant, root and all, to remove it. To harvest the top of the plant, simply cut the plant close to the base using sharp scissors. Chicory can be used in fresh or dried form as a tea or tincture.

Matthew Wood says that traditional herbalists and physicians indicated the use of chicory to improve digestive and metabolic process, stating that chicory not only enhances these functions, but then helps the body absorb the material into the blood. This is due to its bitter properties and effect on the liver (Wood, 2008).

Yarrow (Achillea millefolium)

One of the first plants I learned to identify and harvest, yarrow holds a special place in my heart. It’s one of my personal herbal allies and a plant that I use often in my home.

Yarrow can grow anywhere from 1-5 feet tall, and has many rough, hairy stems sprouting from a rhizomatous root. Bipinnate leaves branch off the stem in a spiral pattern with larger leaves at the base of the plant and smaller leaves at the top (“Yarrow,” n.d.). The leaves are finely segmented giving them a feathery look, and the creamy white, daisy-like flowers grow in flattened, terminal, loose heads, or cymes (Grieve, 1971).

Yarrow can be harvested as soon as the flowers have bloomed. It’s recommended to harvest mid-morning, after the dew has dried and before the sun’s heat evaporates lighter volatile oils. If using the whole plant, grab at the base of the stem and gently pull upward to pull the plant out of the soil, roots and all. If only harvesting the tops of the plant, using sharp scissors or shears, cut 6 inches above the base of the plant. Yarrow can be used in fresh or dried form in teas, tinctures, oils, salves, and syrups.

Rosemary Gladstar suggests using yarrow to increase circulation in order to open the pores and induce sweating as a way to gently lower body temperature. She also suggests it as a first-aid herb to slow internal and external bleeding, to relax cramping of the digestive and reproductive organs, and as an antiseptic wash for wounds (Gladstar, 2008). Hoffmann adds that yarrow has an affinity for the urinary system when used fresh, that it’s toning to the vascular system, and that it stimulates digestion (Hoffmann, 2003).

Bee Balm (Monarda spp.)

The bright red color of bee balm excites me every time I see it growing along the road side because I know it’s time to find a secluded little spot so I can harvest some of it.

Bee balm is a member of the mint family (Lamiaceae), and characteristic of plants in the mint family, it grows anywhere from 3-5 feet tall on a square, hairy stem with ovate shaped leaves with crenate edges that grow opposite one another. Flowers are made up of 20-50 narrow, tubular, bilabiate flowers that vary in color depending on the species.

Bee balm is ready to harvest when the flowers are in full bloom. To harvest, cut the whole plant, 6 inches above ground level, with sharp shears. Bee balm can be used fresh or dried in all types of herbal preparations.

Herbalist Rosalee de la Forêt suggests using bee balm for oral infections of the mouth and digestive tract, to discourage fungal growth in and on the body, to diffuse the heat of fevers from viral infections, to bring on delayed menses, and is great for people who are uptight, nervous, or anxious (Forêt, n.d.). Matthew Wood expounds on bee balm’s action as a nervine, categorizing even further by saying that it’s a stimulating nervine based on its hot, pungent taste and its warming, diffusive energetics (Wood, 2009).

Jewelweed (Impatiens capensis, I. noli-tangere, I. pallida)

Due to the trouble that poison ivy causes, I had to learn how to identify and harvest jewelweed before I ever considered myself an herbalist.

Jewelweed is a member of the touch-me-not family (Balsaminaceae) and can grow to 4-5 feet tall. It has translucent-like, watery stems with swollen joints, and it branches out in different directions. Leaves are ovate, thin, smooth (almost wax-like), serrated, and light green-grey in color, and they have a silvery shimmer to them when placed in water. Jewelweed has a distinct irregular blossom (usually yellow or orange in color) with 5 petals (2 of which are united), 3 sepals, and 5 stamens. Seed capsules, when mature and full of seeds, explode, throwing seeds near and far, when touched giving this plant its common name—touch-me-not (Elpel, 2013; Grieve, 1971).

To harvest jewelweed, clip the smaller branches with a pair of sharp scissors. This plant is mostly used in fresh form, but it can also be juiced or gently boiled in water and frozen into ice cubes to preserve it. It’s most commonly used as a poultice or infused in water, witch hazel, or vinegar, but some people do use it dried in infused oils, salves, and soaps.

Jewelweed is a well-known astringent herb and is commonly used for external skin conditions. It has cooling, moistening energetics (Grieve, 1971).

Red Clover Blossoms (Trifolium pratense)

Red clover can be found in fields, yards, along fence rows, and many other places where plants are left to grow freely making the blossoms one of many flowering herbs to forage in late summer.

Red clover blossoms are pink to purple in color and sit atop a long, slender, hairy stem complete with distinctive trifoliate leaves with smooth edges and rounded bases and tips that have a white V-shape on them (“Red Clover,” n.d.).

To harvest red clover blossoms, simply pinch the blossoms off between your thumb and forefinger. Like many plants, harvesting flowers encourages new growth which means you can get multiple red clover blossom harvests in one year!

Red clover is a great herb for supporting the liver, giving it a reputation as an herbal ally for skin conditions. Not only that, but it’s useful for respiratory conditions where spasms and mucous are present (Hoffmann, 2003). Botanist Dr. James Duke says that red clover is often used for balancing hormones and aiding women through menopause due to its strong concentration of natural estrogens (Duke, 2000).

Learn more about red clover and how to use it in these posts: Red Clover Blossoms, Red Clover, Red Clover, Bring Healing On Over, and Is Red Clover Safe During Pregnancy & Breastfeeding.

St. John’s Wort

St. John’s wort is a perennial that grows around 3 feet tall. It can often be found near meadow drainages, creeks, and foothills. It likes plenty of sun and dry soil. Finding St. John’s wort in cities, in parking lots, and in places where you wouldn’t think much would grow is a testament to the fortitude of this plant and its ability to come through adversity to be of service.

When foraging for St John’s wort, look for its opposite-patterned leaves and branches. The leaves and sepals are oblong in shape and three times longer than they are wide. The leaves are stalkless, and if held to the sky, light will shine through the small dots. There are many long stamen that come together in three bunches and pop out of the center of the flower. St. John’s wort has a reddish, woody stem base. Numerous lengthy stamens emerge from the center of the flower and gather in three groups. The stem base of St. John’s wort is woody and reddish.

And because we love seeing what you’re up to, don’t forget to share your summer foraging finds with us on social media by tagging #myherbalstudies. We’d love to check it out!

REFERENCES

Bee Balm Monograph. (n.d.). Retrieved on July 22, 2017 from https://herbarium.theherbalacademy.com/monographs/#/monograph/5109

de la Forêt, R. (n.d.). Bee Balm, our Native Spice. Retrieved July 25, 2017, from http://www.herbalremediesadvice.org/bee-balm.html

Duke, J. A. (2000). The green pharmacy herbal handbook: your comprehensive reference to the best herbs for healing. New York: St. Martins Paperbacks.

Elpel, T. J. (2013). Botany in a day: the patterns method of plant identification. Pony, MT: HOPS Press.

Gladstar, R. (2008). Rosemary Gladstar’s herbal recipes for vibrant health: 175 teas, tonics, oils, salves, tinctures, and other natural remedies for the entire family. North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing.

Grieve, M. (1971). A modern herbal. New York: Dover Publications.

Hardin, K. (2009). A Much Needed Renewal: Peach Bliss. Retrieved July 22, 2017, from http://kivasenchantments.com/a-much-needed-renewal-peach-bliss.html

Hardin, K. (2007). Sweet Medicine: Healing with the Wild Heart of Rose. Retrieved July 22, 2017, from http://bearmedicineherbals.com/sweet-medicine-healing-with-the-wild-heart-of-rose.html

Hoffmann, D. (2003). Medical herbalism: the science and practice of herbal medicine. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

mcdonald, j. (n.d.). Mullein. Retrieved July 22, 2017, from http://www.herbcraft.org/mullein.html

Mullein Monograph. (n.d.). Retrieved on July 22, 2017 from https://herbarium.theherbalacademy.com/monographs/#/monograph/2031

Peach Monograph. (n.d.). Retrieved on July 22, 2017 from https://herbarium.theherbalacademy.com/monographs/#/monograph/5110

Red Clover Monograph. (n.d.). Retrieved on July 22, 2017 from https://herbarium.theherbalacademy.com/monographs/#/monograph/1018

Red Raspberry Monograph. (n.d.). Retrieved on July 22, 2017 from https://herbarium.theherbalacademy.com/monographs/#/monograph/1017

Rose Monograph. (n.d.). Retrieved on July 22, 2017 from https://herbarium.theherbalacademy.com/monographs/#/monograph/1027

Sarrell, E. M., Cohen, H. A., & Kahan, E. (2003). Naturopathic Treatment for Ear Pain in Children. Retrieved July 22, 2017, from http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/111/5/e574.long

Wood, M. (2008). The earthwise herbal: a complete guide to Old World medicinal plants. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Wood, M. (2009). The earthwise herbal: a complete guide to New World medicinal plants. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Yarrow Monograph. (n.d.). Retrieved on July 25, 2017 from https://herbarium.theherbalacademy.com/monographs/#/monograph/1022