Creating a Local Materia Medica With Motherwort

Motherwort is the gift that keeps on giving in my garden. A member of the tenacious mint family (Lamiaceae), she self-seeds herself prodigiously. Her tenacity is nothing a little weeding can’t take care of, and in turn, I have set aside a designated patch where she can reseed to her heart’s content.

Let’s learn how to identify and use this backyard medicine for your local materia medica!

Creating a Local Materia Medica With Motherwort

Identifying Motherwort

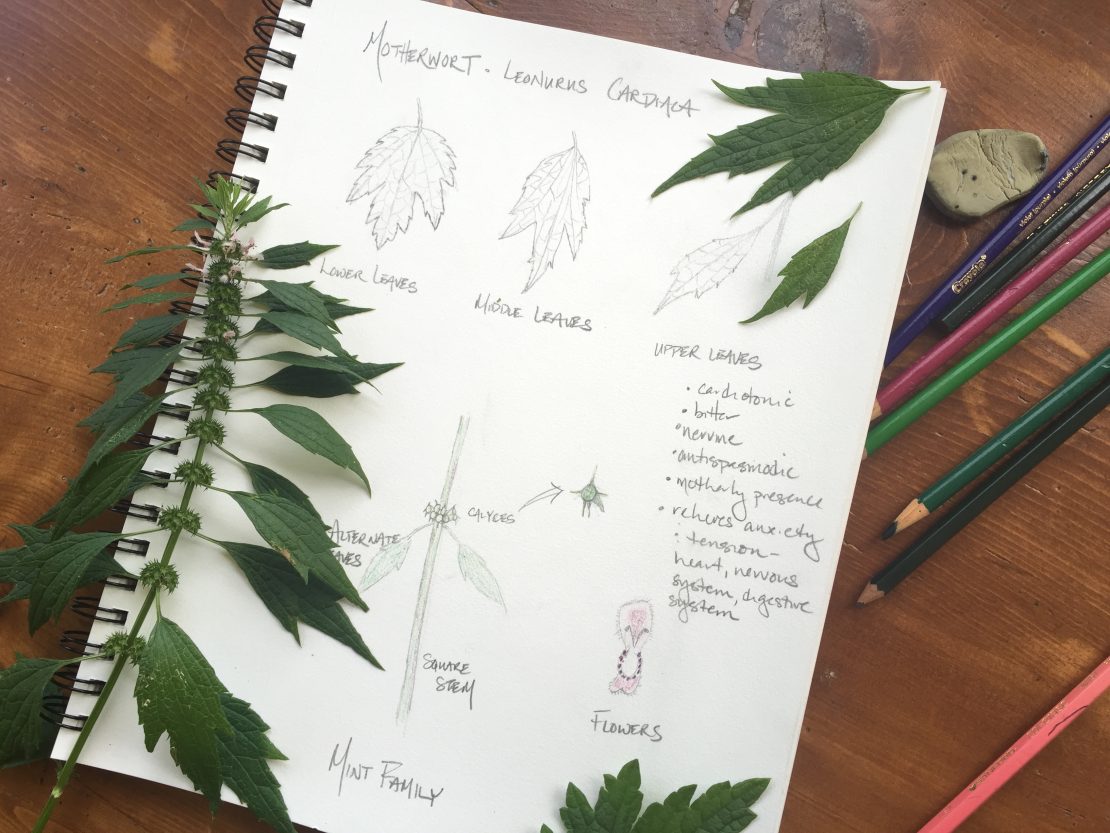

As with all mints, motherwort has some distinctive botanical features: a square stem, opposite leaves, and irregular flowers with bilateral symmetry.

It grows from two to ten feet tall on a smooth, pronouncedly square and sturdy main stem with many branching stems. The stem becomes redder as the plant matures each season.

The opposite leaves are dark green above and pale green below with deep veins. They become progressively smaller and change shape as they ascend the stem. The lower leaves have three to seven unequal, toothed palmate lobes (typically five cleft lobes and several coarse teeth) while the middle leaves are three-lobed with a few teeth and the upper leaves lanceolate to ovate with two teeth.

The small, fuzzy white or pink tubular flowers have two lips, often with purple dots on the lower lip. The flowers are arranged in whorls around the leaf axils, “six to fifteen in a whorl” (Grieve, 1931). The calyces surrounding the flowers and seeded fruits are rather prickly to the touch and can elicit a surprised “Ouch!” during harvest. The stalks, flowers, and leaves of motherwort are typically harvested during full bloom in mid to late summer (Foster, 1993; Grieve, 1931).

Motherwort Medicine

Motherwort’s Latin botanical name is Leonurus cardiaca: lion hearted. This is a bold name, bestowed in part due to the plant’s resemblance to a lion’s tail.

One of my favorite Latin botanical names is Nymphaea caerulea, the Egyptian Lotus. It is soft, beautiful, and rolls off my tongue, eliciting visions of water nymphs floating on lily pads. Yet if I’m caught in a dark, dangerous alley and I get to choose one botanical name as my protector, I’m going with Leonurus cardiaca. Motherwort is a tough plant, fiercely protective (think of those prickly calyces), who will have my back in challenging situations.

Cardiotonic

As a lion-hearted herb should, motherwort is used to strengthen the heart and is considered a cardiotonic. Its diuretic action can reduce blood pressure while it also stimulates circulation, bringing more oxygen to the blood (Herbal Academy, n.d.).

Its antispasmodic and nervine actions also relieve the spasm, tension, and anxiety that accompany heart palpitations and irregular heartbeat (Bennett, 2014; Hoffmann, 2003). It has long been used for the heart in this manner—in The English Physician (1652), herbalist and physician Nicholas Culpeper writes, “Motherwort, is held to be of much use for the trembling of the Heart, and in faintings and swoonings from whence it took the name Cardiaca.”

Nervine

It is the softer side of motherwort, as a supportive nervine, with which I am most familiar. Again, as Nicholas Culpeper (1652) describes,

“There is no better herb to take melancholy vapours from the heart, to strengthen it, and make a merry, cheerful, blithe soul than this herb.”

It helps one release the anxiety and tension that accompany stress and overwhelm—not just on a physical level, as in the case of heart palpitations, but also on the emotional level that may be at their root. In some very difficult and stressful situations in which I have felt anxious and vulnerable with a racing heart, I have turned to motherwort for acute emotional support. Within several minutes of taking a tincture, I was able to breathe more deeply and gain the perspective I needed to see the forest for the trees and formulate a more measured, calm, and rational response. While motherwort’s motherly presence calmed me, her strong, no-nonsense nature bolstered me—restoring my backbone, so-to-speak.

Reproductive

Of course with a name like “motherwort,” which means “mother’s herb,” there is more to her story: she is a mother plant supportive to women’s health and wellness.

Culpeper (1652) describes, “it makes Women joyful Mothers of Children, and settles their Wombs as they should be, therefore we call it Motherwort.” The first part of this quote again refers to motherwort’s nervine action, which can alleviate the anxiety and overwhelm a new mother may feel after childbirth, enabling her to enjoy her new role. It also eases cramps and is used to restore the uterus following childbirth.

As a digestive bitter, motherwort stimulates the liver to break down hormones, helping to regulate menstrual cycles and balance symptoms of PMS and menopause (Sage Maurer, personal communication, 2013).

It’s also an emmenagogue so is not for use by pregnant women.

Energetics of Motherwort

Energetically, motherwort is a cooling, bitter herb. Really bitter! The tea is not for the faint of heart, so I typically opt for motherwort tincture—in fact, it is the first tincture I ever made as a fledgling herbalist (and the next tincture I made, too, since the motherwort in my garden was in full bloom).

Due to its bitter action, motherwort is helpful for stimulating the digestive system and liver to improve sluggish digestion. Its nervine action soothes anxiety or nervousness that may be at the root of digestive difficulties. For both reasons, motherwort can be an effective addition to bitters blends to support healthy digestion.

You likely noticed a recurring theme here—motherwort eases the anxiety and tension that are at the root of imbalance, be it in the physical heart, the emotional heart, or the digestive system. While she may be large, tough, and prickly in appearance, motherwort is above all defined by her ability to mother and soothe, firmly guiding us back to balance.

Start Building your Materia Medica with these free pages!

Interested in learning more? Check out our motherwort monograph (and many more plant monographs) in The Herbarium!

REFERENCES

Bennett, R.R. (2014). The gift of the healing herbs. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.

Culpeper, N. (1652). The English physician. Retrieved on 6/15/2016 from http://doc.med.yale.edu/historical-old/culpeper/m.htm

Foster, S. (1993). Herbal renaissance. Layton, UT: Peregrine Smith Books.

Grieve, M. (1931). A modern herbal. Retrieved on 6/15/2016 from http://www.botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/m/mother55.html

Herbal Academy. (n.d.). Motherwort monograph. Retrieved on 6/15/2016 from http://herbarium.herbalacademyofne.com

Hoffmann, D. (2003). Medical herbalism. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.