A Foraged Feast: Nutritional Value of Edible Wild Food

Since we launched our foraging course, we’ve been fascinated by the nutritional density of edible wild food varieties compared to their cultivated counterparts. As a sneak peek into The Foraging Course, we’re diving into this topic with an excerpt pulled directly from Lesson 2.

Wild edibles tend to contain more beneficial nutrients like vitamins and minerals on a per-weight basis than cultivated foods (Milburn, 2004). This is attributed to a variety of causes. First, cultivated foods like vegetables have been selected for many generations for their size and hardiness rather than their nutritional value. All cultivated foods originated as wild plants, and over the long history of agriculture, likely starting around 12,000 years ago (Uekoetter, 2010), humans have saved seeds and hybridized plants to genetically select larger, easy-to-grow varieties. Such plants make for greater crop yields, but tend to contain fewer nutrients than their wild counterparts (Davis et al., 2004).

With the advent of agriculture, humans began to focus on select cultivated food staples rather than the wide diversity of foods available in the wild, leading to a significant reduction in overall dietary diversity (Grivetti & Ogle, 2000). Additionally, cultivated foods are often grown via monocropping in conventional agricultural systems that lead to nutrient depletion in the soil, and as a result the food grown in it.

Wild edible foods tend to grow within biodiverse communities, enabling them to garner nutrients from the richer soil conditions supported by this biodiversity (Blair, 2014). Additionally, fresh wild foods can be eaten on the day of harvest, whereas cultivated foods often lose nutrients during transportation and storage (Blair, 2014).

Traditional Versus Modern Diets

So, what’s the big deal about nutrient-dense foods? Why are they so vital in supporting our wellbeing? To answer these questions, we can first look at what happens when we don’t eat nutritious foods. Many chronic and degenerative diseases, including coronary heart disease, hypertension, type 2 diabetes, and autoimmune diseases, have become common causes of mortality in the industrialized world, but are rare in remaining hunter-gatherer cultures and other non-Westernized populations (Carrera-Bastos et al., 2011). This has led researchers to cite “a mismatch between our ancient physiology and the Western diet and lifestyle” as a possible cause for the high prevalence of these so-called “diseases of civilization” (Carrera-Bastos et al., 2011, Abstract).

Our Neolithic ancestors consumed diets that tended to be lower in calories and higher in nutrients (Milburn, 2004), whereas modern diets are often higher in carbohydrates and processed “junk” foods that provide empty calories and little nutrition (Carrera-Bastos et al., 2011; Masé, 2013). For example, refined sugars and vegetable oils are devoid of most nutrients, but represent 36% of calories consumed in a typical diet in the United States (Carrera-Bastos et al., 2011). In the words of foragers “Wildman” Steve Brill and Evelyn Dean (1994), “Most Americans are overfed and malnourished” (p. 5). Of course, this trend extends well beyond the boundaries of the United States.

Thus, modern food choices, conventional agricultural methods, and the transport and storage of food have all contributed to a lack of nutrients in the modern diet. Even a moderate level of nutrient deficiency is considered a risk factor for a broad range of chronic degenerative diseases (Carrera-Bastos et al., 2011). This nutritional lack in modern foods has led to the enrichment of staples such as cereals and grains with vitamins and minerals, and many individuals seek out supplements to compensate for nutrient deficiencies. However, these isolated and/or synthesized vitamins and minerals often come in a different form than those found in foods and are not as readily absorbed by the body (Scrinis, 2013). They also do not benefit from the combination with other elements naturally found in foods, and thus lack the synergistic interactions that are present in whole foods and traditional food combinations (Scrinis, 2013).

To address issues related to the standard modern diet and its associated deficiencies, many herbalists, nutritionists, and researchers are calling for a return to a more traditional diet, characterized by a greater diversity of whole, nutrient-dense foods. The inclusion of wild foods certainly fits the bill for both diversity and nutrient density. As Brill and Dean (1994) put it, “Although wild foods won’t make you live forever, their extra nutrients often help forestall or prevent degenerative disease” (p. 6). A well-nourished body is a healthy body; below we’ll examine how specific vitamins and minerals contribute to overall wellbeing.

Nutritional Benefits of Wild Edible Foods

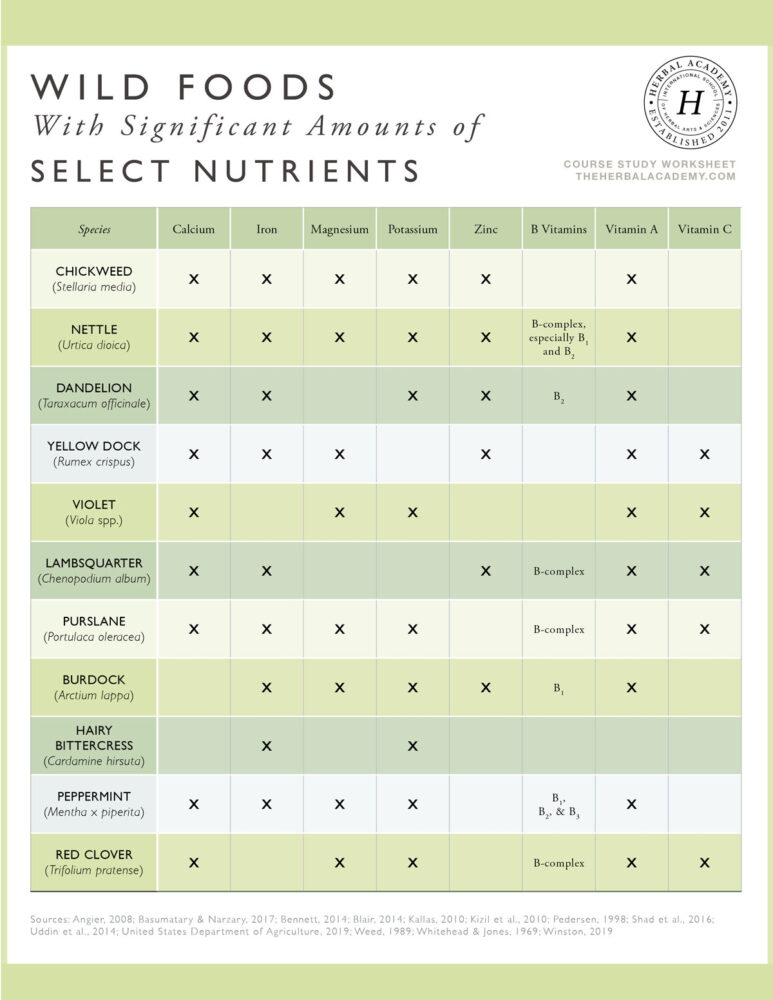

Some of the nutrients that are most commonly available in wild plants include minerals, such as calcium, magnesium, zinc, potassium, and iron, as well as vitamins A, B, and C (Blair, 2014; Milburn, 2004; Weed, 1989). This is by no means an exhaustive list, but as we will see, these nutrients are essential to our overall health.

Calcium, best known for its importance in maintaining healthy bones and teeth, has many other functions in the body including supporting immune health and regulating muscular relaxation and contraction, blood pressure and clotting, and nerve function (University of Michigan [UM], 2018a). Adequate calcium consumption is also associated with improved symptoms of premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and a reduced risk of colon cancer (Ryan-Harshman & Aldoori, 2005).

As the chart below shows, many wild edible foods are rich in calcium. Dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) leaves, for example, have more calcium per weight than spinach (Brill & Dean, 1994)!

Magnesium is a mineral that complements calcium in the body, meaning the absorption of these two minerals is related, and some functions of these minerals balance each other. Magnesium is also important for building bones and teeth, and it supports nerve transmission, healthy muscle contraction and relaxation, and immune system health (UM, 2018a). Getting enough magnesium is thought to help prevent hypertension, cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis (UM, 2018a), type 2 diabetes, Alzheimer’s disease, and migraine headaches (Ware, 2020). Magnesium is also used to help ease feelings of stress and anxiety (Ware, 2020). Magnesium helps skeletal muscles and the smooth involuntary muscles of the cardiovascular system, digestive system, and uterine muscle relax.

Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) aerial parts and red clover (Trifolium pratense) aerial parts both include particularly high levels of magnesium. In general, increasing wild plants and green vegetables in your diet will boost your magnesium consumption.

Zinc helps to make proteins and genetic material, and thus is required for fetal development and growth (UM, 2018a). It also supports the immune system and helps with the body’s wound-healing and blood-clotting abilities (Harvard Medical School [HMS], 2018).

Chickweed (Stellaria media) aboveground parts and hairy bittercress (Cardamine hirsuta) aboveground parts both contain notable levels of zinc.

Potassium is necessary for regulating muscle contractions, including the heartbeat, and maintaining proper fluid balance within the body (HMS, 2018); it is also an important factor in nerve transmission (UM, 2018a). Purslane (Portulaca oleracea) aboveground parts and nettle (Urtica dioica) leaf, young stalk, and seed are two wild edible foods that contain notable levels of potassium.

Iron is essential for the creation of hemoglobin, which carries oxygen to red blood cells, as well as amino acids, hormones, neurotransmitters, and collagen (HMS, 2018). A lack of iron can lead to symptoms of anemia, including fatigue, dizziness, brain fog, and chest pain (National Institutes of Health, n.d.).

Yellow dock (Rumex crispus) root has been used for anemia due to its iron content as well as its ability to promote the absorption of iron. It’s helpful to combine dock with other iron-rich herbs such as nettle (Urtica dioica) leaf, chickweed (Stellaria media) aboveground parts, and seaweed for the most benefit (Katz, 2016).

While we are on the subject of taproots, you’ve probably heard that carrots, not very different from some wild plants we love, are high in vitamin A. It is a bit of a misnomer to say that plants contain vitamin A; what they contain is beta-carotene, a precursor that is converted into vitamin A by the body (UM, 2018b). Vitamin A is essential to maintaining the integrity and health of all surface tissues, from the skin to the mucosal lining of the gut, bladder, respiratory tract, and eyes (Gilbert, 2013). It supports eye health and good vision, the growth of bones and teeth, and the health of the immune system (UM, 2018b). Interestingly, dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) leaves contain more vitamin A than carrots (Brill & Dean, 1994)!

B-vitamins are important, right? But can you get vitamin-B from plants? There are eight types of vitamin B: thiamine (B1), riboflavin (B2), niacin (B3), pantothenic acid (B5), pyridoxine (B6), biotin (B7), folate (B9), and cobalamin (B12). B-complex vitamins have a broad range of functions in the body, such as aiding in metabolism to help convert food into energy (Kubala, 2018). They are essential for the health of the skin as well as the digestive and nervous systems (UM, 2018b). Many wild edible foods contain B-complex vitamins, including lambsquarter (Chenopodium album) leaf and young stalk and nettle (Urtica dioica) leaf, stem, and seeds.

Vitamin C is needed for protein metabolism; it also provides support to the immune system, aids in the absorption of iron (UM, 2018b), and helps produce collagen, which aids in wound healing (Nordqvist, 2017). As an antioxidant, vitamin C protects the body from oxidative stress and can help to reduce damage from inflammation, among many other benefits (Nordqvist, 2017). Lambsquarter (Chenopodium album) raw leaves are super high in vitamin C, and just 3.5 ounces contain 96% of the daily recommended amount (Blair, 2014)!

Here is a table that lists the plants discussed in this lesson and which of the above nutrients their edible portions contain:

If you’re interested in learning how to harvest and use wild edible plants, including those mentioned in this article, then check out The Foraging Course. This 5-lesson road map is a fast track to foraging, including safe tips and practices, 24 in-depth plant monographs, and delicious recipes for whipping up meals from wild edible food. Recipes include:

- Burdock Seaweed Soup

- Chickweed Smoothie

- Dead Nettle and Chickweed Fritters

- Hairy Bittercress and Wild Onion Risotto

- Lambsquarter Energy Bars

- Nettle Pesto

- Purslane Peach Pie

- Red Clover Blossom Biscuits

- And so much more!

Enroll in The Foraging Course Today!

REFERENCES

Blair, K. (2014). The wild wisdom of weeds: 13 essential plants for human survival. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing.

Brill, S., & Dean, E. (1994). Identifying and harvesting edible and medicinal plants in wild (and not so wild) places. New York, NY: Hearst Books.

Carrera-Bastos, P., Fontes-Villalba, M., O’Keefe, J., Lindeberg, S., & Cordain, L. (2011). The western diet and lifestyle and diseases of civilization. Research Reports in Clinical Cardiology, 2, 15-35. https://doi.org/10.2147/RRCC.S16919

Davis, D., Epp, M., & Riordan, H. (2004). Changes in USDA food composition data for 43 garden plants, 1950-1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition, 23(6), 669-682. https://doi.org/10.1080/07315724.2004.10719409

Grivetti, L., & Ogle, B. (2000). Value of traditional foods in meeting macro- and micronutrient needs: The wild plant connection. Nutrition Research Reviews, 13, 31-46. https://doi.org/10.1079/095442200108728990

Harvard Medical School. (2018). Precious metals and other important minerals for health. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/precious-metals-and-other-important-minerals-for-health

Katz, N.J. (2016). Yellow dock herbal monograph. Natural Herbal Living, March 2016, 4-9.

Milburn, M. (2004). Indigenous nutrition: Using traditional food knowledge to solve contemporary health problems. American Indian Quarterly, 28(3-4), 411-434. https://doi.org/10.1353/aiq.2004.0104

National Institutes of Health. (n.d.). Iron-deficiency anemia. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Retrieved from https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/iron-deficiency-anemia

Ryan-Harshman, M., & Aldoori, W. (2005). Health benefits of selected minerals. Canadian Family Physician, 51(5), 673-675.

Scrinis, G. (2013). Nutritionism: The science and politics of dietary advice. New York, NY: Columbia University Press.

Uddin, K., Juraimi, A., Hossain, S., Nahar, A., Ali, E., & Rahman, M. (2014). Purslane weed (Portulaca oleracea): A prospective plant source of nutrition, omega-3 fatty acid, and antioxidant attributes. The Scientific World Journal, 2014, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/951019

Uekoetter, F. (Ed.) (2010). The turning points of environmental history. Pittsburgh, PA: University of PIttsburgh Press.

University of Michigan. (2018a). Minerals: Their functions and sources. Retrieved from https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/ta3912

University of Michigan. (2018b). Vitamins: Their functions and sources. Retrieved from https://www.uofmhealth.org/health-library/ta3868#ta3868-sec

Ware, M. (2020). Why do we need magnesium? Medical News Today. Retrieved from https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/286839

Weed, S. (1989). Wise woman herbal: Healing wise. Woodstock, NY: Ash Tree Publishing.