Botany Beginnings: Who was Theophrastus?

Approximately 2,300 years ago, a time which we can somewhat imagine through the marble monuments still standing and the relatively few parchments that have survived, a person named Theophrastus (c. 370 BCE – c. 287 BCE) reportedly wrote 227 books about animals, trees, shrubs, fruits, and flowers. Although he wasn’t the only scientific writer at the time, nor the first to study plants, he would become known as the “father of botany” because his descriptive writings, specifically his surviving book, Enquiry into Plants (Historia Plantarum), helped create a new frontier in scientific botanical terminology.

According to Dictionary.com, botany is “the scientific study of plants, including their classification, structure, physiology, ecology, and economic importance.” For anyone who has studied plants, it quickly becomes obvious how complex and complicated the science of nature truly is. Theophrastus’ lifetime of work helped separate botany from the philosophical, mythic, and culinary realms and introduced it into the forefront of scientific inquiry. His achievements continue to help us in our own study of plants—examining, understanding, and appreciating the flora of both then and now.

Theophrastus, depicted as a medieval scholar in the Nuremberg Chronicle (Wiki commons).

Who was Theophrastus?

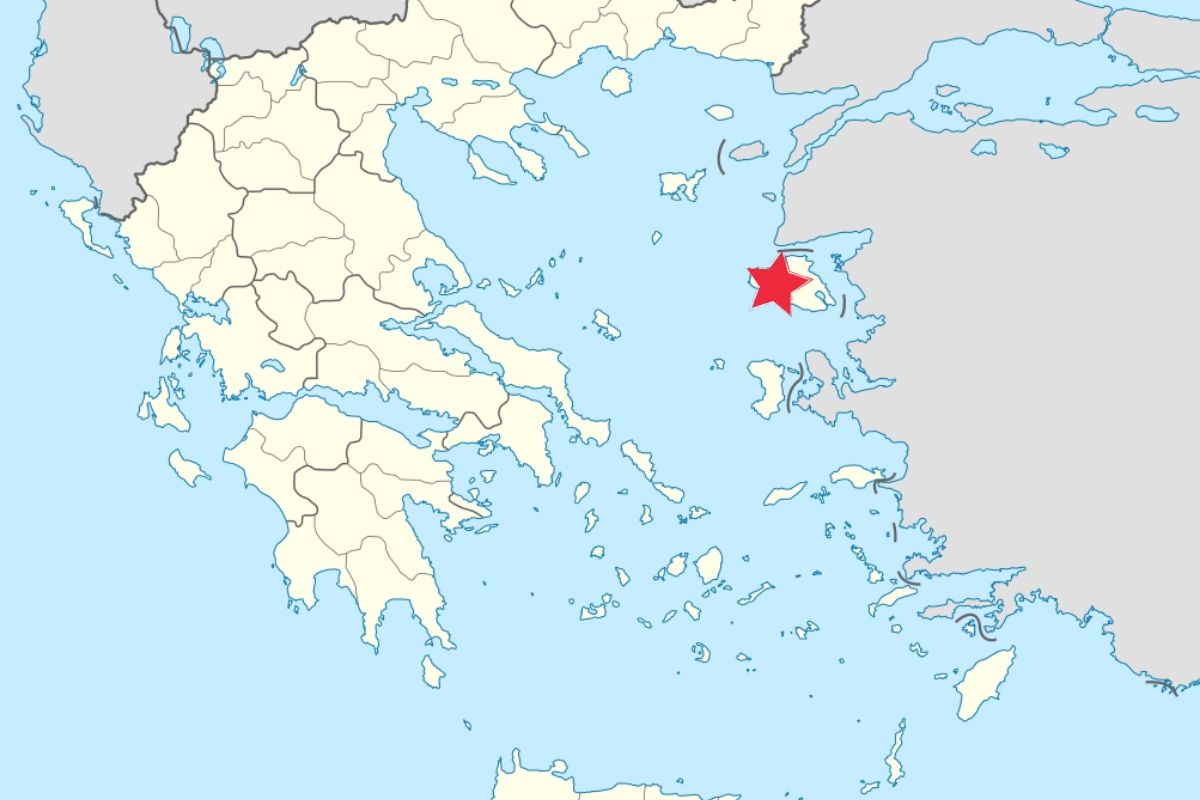

Theophrastus was born in Eresus, Lesvos, an island in the Aegean Sea, where the lyric poet Sappho was born 250 years earlier. During his lifetime, there were countless battles between Greek city states and with foreign lands, including the conquests by Alexander the Great and his vast army. Despite the common sound of battle cries across the Mediterranean, Persia, and Asia, there were also advances in education, with a philosophical thread of ancient thought folded into everyday life. With public lectures available to the male public in Athens’ main square, or agora, and renowned philosophers examining the meaning of life, Theophrastus lived during a pivotal point in ancient Greek history during which he could tap into his vast curiosity on many thriving subject matters (Hughes, 2012).

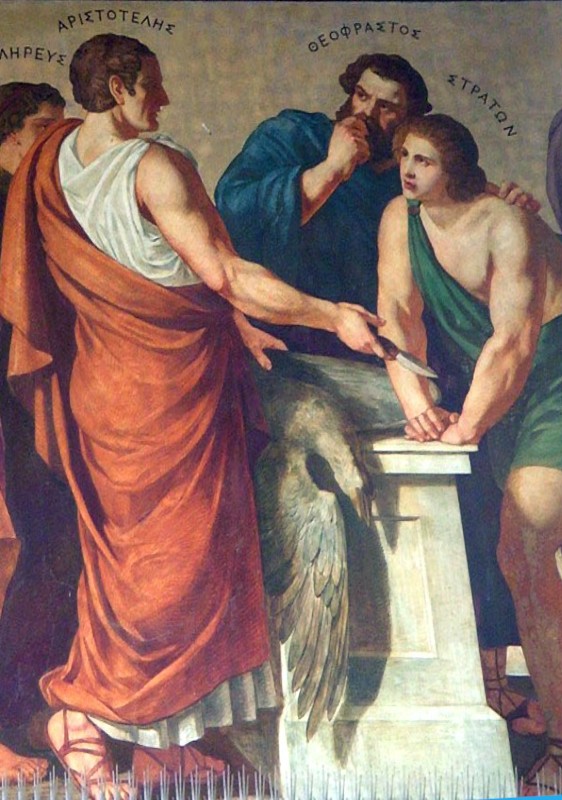

As a boy, Theophrastus attended The Academy, a philosophical school founded by Plato (c. 428 BCE – c. 348 BCE) in Athens. He studied with Aristotle (384 BCE – 322 BCE), the renowned philosopher who would later change Theophrastus’ name from his original Tyrtamus, to indicate the grace of his conversation, meaning “divine expression” from the ancient Greek Θεός “god” and φράζειν “to phrase” (Laërtius, 1925).

In his twenties, Theophrastus returned to Lesvos for several years and studied with Aristotle on various topics related to the natural sciences on both plants and animals. Specifically, this sojourn allowed him to carry out extensive botanical studies of the area (Witztum, 1991). Scholars today recognize that the work Theophrastus and Aristotle accomplished together “cannot be exaggerated: [for example] the descriptions of marine zoology… were so excellent in detail and accuracy that this branch of Peripatetic ichthyology and physiology retained a peerless status” well until the 1500s (Scarborough, 2006, p. 6). Their work together amassed countless scientific understandings of plants and animals.

Theophrastus, however, did occasionally have opposing views from Aristotle, specifically his separation of science from teleology, which offers explanation by reference to some purpose, end, goal, or function (Britannica.com, n.d.). Aristotle, according to his writings, viewed the natural world as being in existence for the sake of human beings. Theophrastus disagreed. Unlike his teacher, he sought to learn not only about the plants and animals in a certain environment, but about the relationships between people and nature. “The forests, fields, seas and farms were the cockpit of all ‘facts’ and the experts were the fishermen, gatherers of wild plants and their parts, and farmers, whose full knowledge of animals and their habits and lives were the ultimate source of the first ‘handbooks’ of comparative anatomy and botany” (Scarborough, 2006, p. 11). Theophrastus eagerly sought to understand plant folklore, which provided him a wider range of information than the philosophical leanings that his teacher was more inclined toward. Fortunately, his writings capture some of the traditions and rituals of these early herbalists.

Despite their differences, Theophrastus and Aristotle’s relationship thrived. When Aristotle died, he bequeathed to him his Peripatetic School in Athens, and according to writers at the time, Theophrastus wrote his books on subjects that he learned from studying with his teacher. His descriptive and detailed scientific writing style helped him stand out among his peers, and as a result, “botany became more restricted to the practical fields of pharmacology, agriculture, astrology, and magic,” rather than being kept constrained in the philosophical fold (Pease, 1952, p. 47).

Aristotle, Theophrastus, and Strato of Lampsacus. Part of a fresco in the portico of the University of Athens painted by Carl Rahl, c. 1888. (Wiki commons)

For thirty-five years, Theophrastus was head of the Peripatetic School, which at the height of its operations accommodated nearly 2,000 students. During this time, he impressively wrote 227 treatises, with titles such as Meteorological Phenomena, Warm and the Cold, On the Senses, and On Stones, and on topics ranging from religion, politics, ethics, physics, mathematics, astronomy, logic, psychology, zoology, and of course, botany (Coonen, 1957). Unfortunately, less than ten of these books have survived. From what we do have, we are able to understand the depth and breadth of his research, as well as more clearly understand the civilization that bequeathed their knowledge to us.

Through his work, Theophratus became known as a gifted teacher and was “liked and deservedly famous for his colourful, vividly illustrated lectures which [also] attracted the generally uninterested…” (Scarborough, 2006, p. 4). His accomplishments as a teacher, scientist, and writer would later inspire Carl Linneaus in the 1700s to name his predecessor the “father of botany.”

Enquiry into Plants

As a pioneer ecologist and naturalist, Theophrastus compiled some of his botanical research into his book, Enquiry into Plants, a combination of nine surviving books. These books were first translated from ancient Greek in the Middle Ages into Latin and eventually into modern English. Each book focuses on a specific plant or environment, with his final book on the medicinal properties of herbs:

- Book I: The Parts of a Plant and their Composition of Classification

- Book II: Propagation, Especially of Trees

- Book III: Wild Trees

- Book IV: The Trees and Plants Special to Particular Districts and Positions

- Book V: The Timber of Various Trees and Its Uses

- Book VI: Under-Shrubs

- Book VII: Herbaceous Plants, Other Than Coronary Plants: Pot-Herbs and Similar Wild Herbs

- Book VIII: Herbaceous Plants: Cereals, Pulses, and ‘Summer Crops’

- Book IX: The Juices of Plants and of the Medicinal Properties of Herbs

Theophrastus’ classification and exacting descriptions of trees, shrubs, under-shrubs, and herbs became a manual that pioneered science, providing insight into how plants were cultivated, their reproduction and botanical structures, their ecological settings and habitats, and their uses in contemporary society. Additionally, his book offered a wide range of advice compiled from an array of sources that were applicable to many areas of life. His book reportedly helped not only current and future scientists, but also his fellow average citizen interested in plants, tradesmen needing better techniques, and medical practitioners seeking remedies. For example, in Book IV, Theophrastus explains how the willow tree grows well in either moist or dry settings, whereas silver firs grow tallest in low-lying settings sheltered from the wind. The wood from this tree was common for ship masts and beams (Coonen, 1957). In Book V, he notes that the timber from maple trees was commonly used for making beds and the yokes of beasts of burden, while elm wood was used for making doors (Coonen, 1957). Not only do we gain a sense of the ecology of the trees and their common practical uses, but we can also gain an understanding of an ancient lifestyle and how they used different natural materials to enhance their civilizations.

In Book IX, his book on medicinal herbs, Theophrastus describes approximately sixty herbs, remedies, and practices, including on aromatic plants, how to collect certain resins, when to harvest roots, plants with magical powers, plant superstitions, the relationship between certain animals and plants, and herbs local only to specific areas, among other intriguing topics. He describes the properties of hellebore (Helleborus cyclophyllus), poppy (Papaver somniferum), wolfsbane (Aconitum anthor), meadow saffron (Colchicum parnassicum), chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus), gum Arabic (Acantha arabica), and marshmallow (Althaea officinalis), to name a few, as well as fertility and anti-fertility drugs used at the time. Mandrake (Mandragora officinarum), for example, “its leaf combined with wheat-meal is beneficial for wounds, the root peeled then soaked in vinegar is good for treating erysipelas, as is [this] for treating gouty conditions, and for inducing sleep, and for the making of aphrodisiacs. It is given in wine or vinegar. [The rootcutters] cut slices of the root into pastilles just as they do with radishes, and string them up to hang out smoky must” (Scarborough, 2006, p. 18).

With the help of his students attending his school, some of whom hailed from outside Athens, as well as possible deliveries from Alexander the Great on his war campaigns in India, Theophrastus was also able to document a variety of native and non-native plants, including cinnamon (Cinnamomum cassia), pepper (Piper nigrum), and frankincense (Boswellia carteri) (Coonen, 1957).

Unlike other scientists of his time, Theophrastus’ descriptions of beneficial plants also included rituals and superstitions that were compiled directly from herbal drug vendors and root diggers. These herbalists, however, were not often respected during this time because of some of their seemingly bizarre or irrational practices (Coonen, 1957). Theophrastus, however, considered them experts on medicinal substances and relied on them as a primary source, especially since they would often share with him their bundles of roots, leaves, and berries, and their expertise with how they cultivated the plants and how they prepared them into herbal preparations (Scarborough, 2006).

One such ritual which Theophrastus documents explains how traditional “customs linked aphrodisiacs with anodynes, since rootcutters say that when one harvests mandrake apples, one is supposed to draw three circles around the apples and the plant with a sword, and to be sure one cuts it while facing westward, and in cutting the second piece, one then does a dance around the plant uttering as much as one can remember about lust, sex, and the full mysteries of erotic passion” (Scarborough, 2006, pp. 13-14). Other rituals required a root harvest only at a specific time of day or facing a certain direction, or which bird must not be watching—if a vulture saw you harvesting centaury (Centaurea salonitana), it could signify great harm. Another superstition advised gatherers to apply oil generously on their bodies before harvesting certain plants, which could have been, perhaps, a precaution against sunburn by using olive oil, which does have elements of sunblock (Scarborough, 2006).

While even today, some of these practices might seem a bit bizarre, Theophrastus did not seek to understand these rituals; he wanted to capture them in order to illustrate the complexity of the relationships between humans and plants, which, to early herbalists, often included an element of divine intervention and sacred intention.

As was his intention during his lifetime, the combination of Theophrastus’ ingenuity and aptitude with a fortunate grace of time has allowed many people to enjoy and learn from his writing far later in the future than he could ever have imagined. These herbal traditions, although not completely applicable any longer, serve as a reminder that plants have a magical power to outlast the brutal elements of time, and help us remember our ever-changing relationship with nature.

Conclusion

Learning about how early botanists and herbalists studied and invoked the beneficial properties of plants awakens our imagination to more than just ancient marble stone and crumbling parchment. In reading ancient texts, we bring back to life traditions, practices, and ideas that were once crucial to society. Fortunately, most of the plants that existed then continue to grow, heal, and inspire us today.

Additionally, understanding how ancient scientists understood the natural world and their relationship to it can help us better understand current-day botany and herbalism and provide a window into how life once was with the same plants that we still cherish. So who was Theophrastus? An ancient human who understood the importance of meticulously studying and documenting the role of plants in sustaining human life, to leave a legacy that we can still appreciate thousands of years later.

REFERENCES

Botany. (n.d.) Retrieved from https://www.dictionary.com/browse/botany

Coonen, L. (1957). Theophrastus revisited. The Centennial Review of Arts & Science, 1(4), 404-418.

Encyclopedia Britannica. (n.d.) Teleology. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/teleology

Hughes, B. (2012). The hemlock cup: Socrates, Athens, and the search for the good life. New York: Vintage Books.

Laërtius, D. (1925). “Theophrastus”. Lives of the Eminent Philosophers (Vol. I, book 5). (Hicks, R. D., Trans.). Loeb Classical Library. 36-50. (Original work published n.d.).

Pease, A. (1952). A sketch of the development of ancient botany. Phoenix, 6(2), 44-51.

Scarborough, J. (2006). Drugs and drug lore in the time of theophrastus: Folklore, magic, botany, philosophy and the rootcutters. Acta Classica, 49, 1-29.

Theophrastus (1916). Enquiry into plants (Vol. I, books 1-5). (Hort, A.F., Trans.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. (Original work published n.d.).

Witztum, A., & Negbi, M. (1991). Primary xylem of scilla hyacinthoides (liliaceae): The wool-bearing bulb of Theophrastus. Economic Botany, 45(1), 97-102.