Starting Herbs From Seed

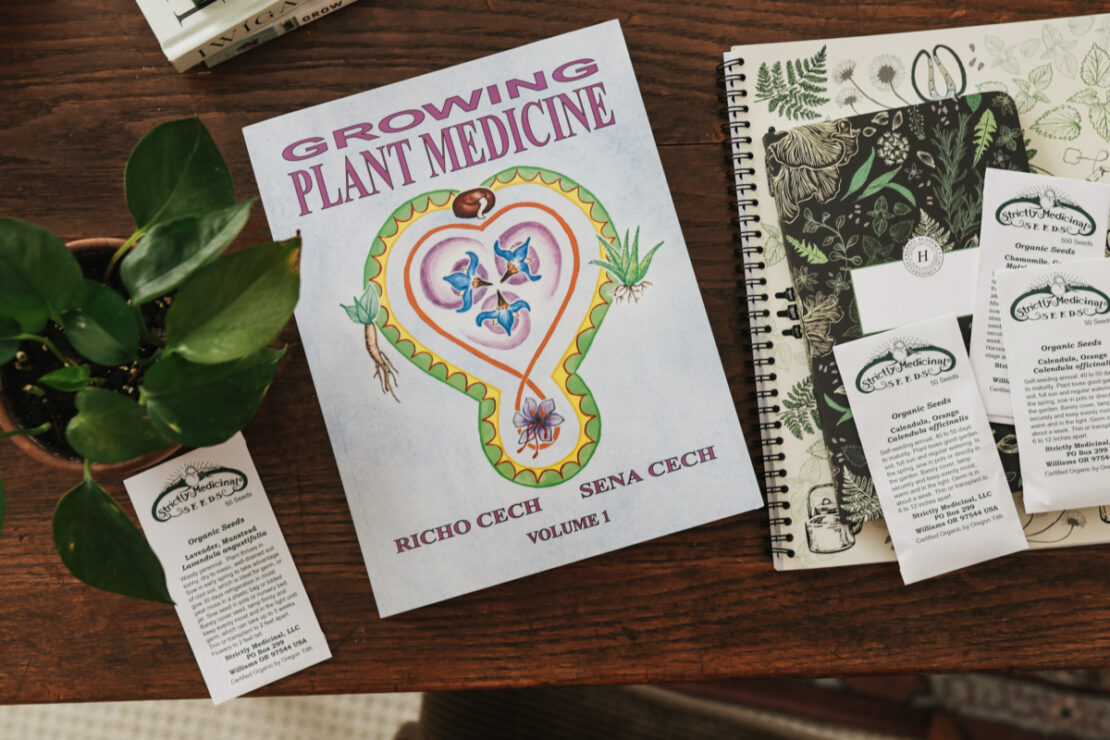

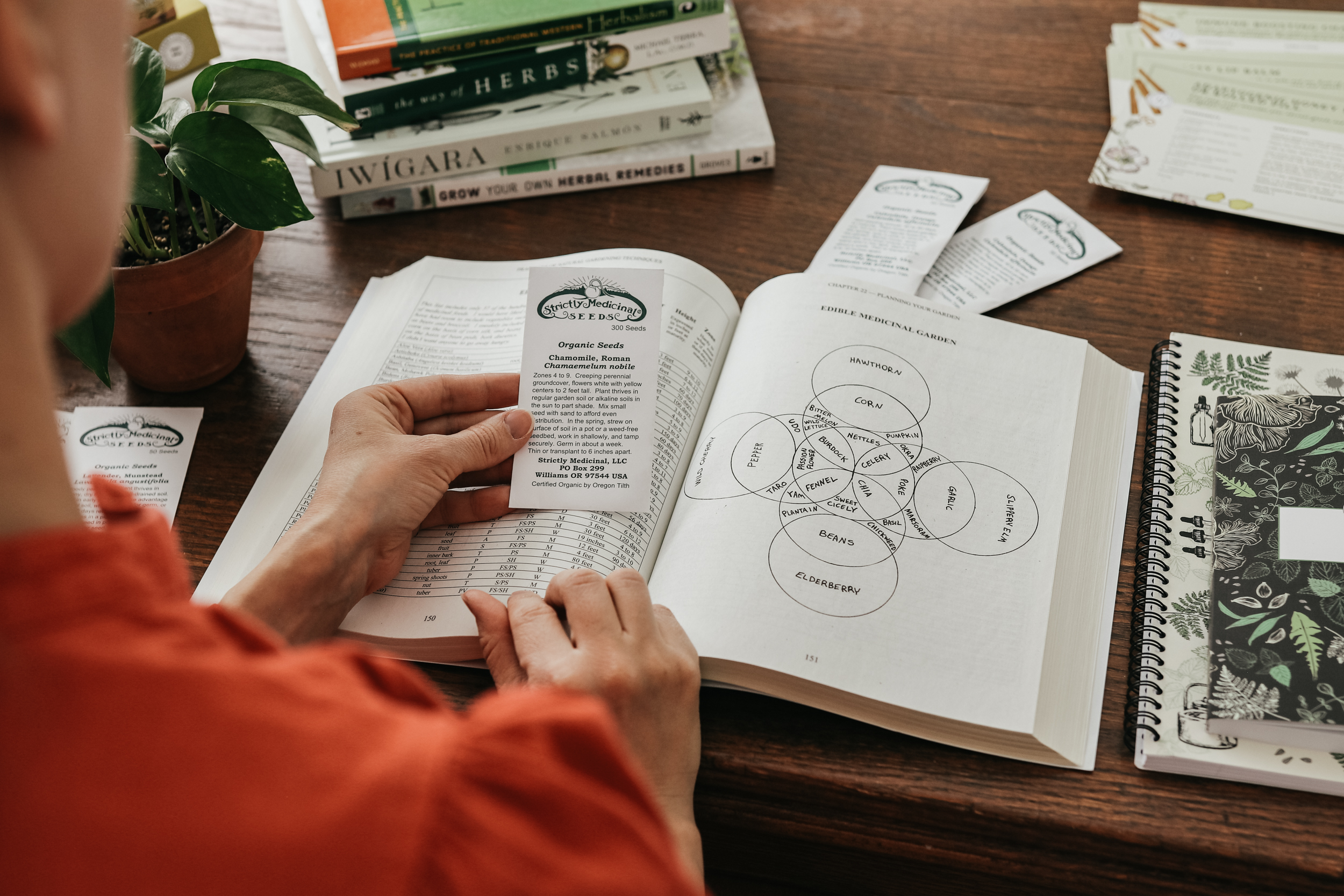

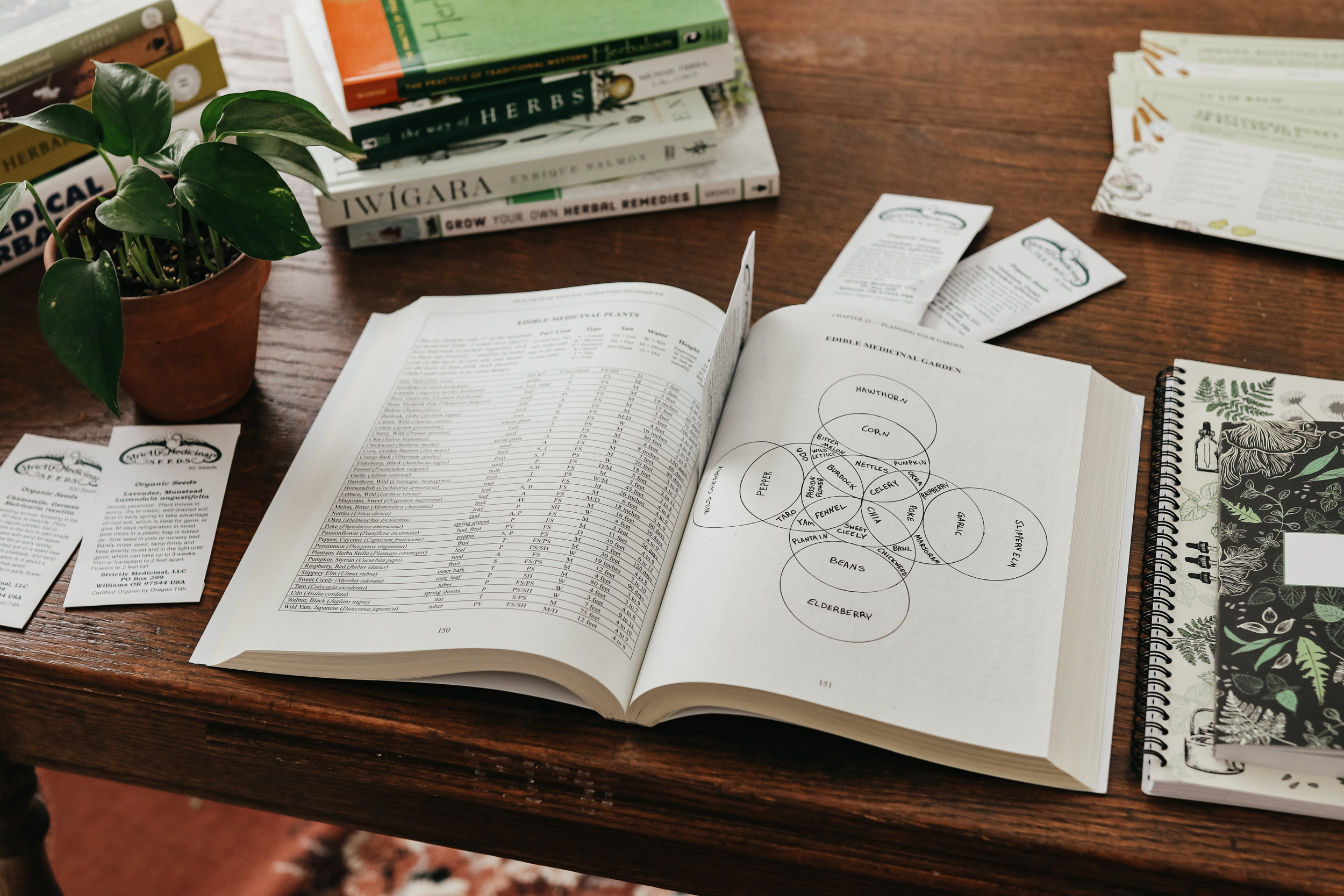

Have you ever wanted to start growing herbs from seed? We are delighted to share our friend Richo Cech’s new book, Growing Plant Medicine: The Medicinal Herb Grower, Volume 1, with you today to give you some base knowledge for starting herbs from seed for your herbal garden. In this book, you’ll discover theory and practice of natural garden techniques, newly augmented with bioregional medicinal plant recommendations, garden plans, and a wonderful herbal materia medica. Filled with ruminations on gardening and herbalism coming from a lifetime of observing, growing, and advocating for medicinal herbs, you’ll delight in this informative and personal read!

The following is an excerpt from Chapter 7 of Growing Plant Medicine: The Medicinal Herb Grower, Volume 1 Expanded by Richo Cech and Sena Cech, and is shared with permission.

SEEDS

Have faith in seeds story. The sagging milk carton, with its precious cargo of dirt and seeds, clutched in both hands and held protectively to my chest, barely survived intact the six-block journey from Lincoln grade school to our stucco house at 406 Magowan Avenue in Iowa City. Surely, it is a sign of great love when our mothers allow us to place such travel-worn, leaky vessels on the windowsill, where light washes in over the porcelain of a kitchen sink, otherwise scrupulously scrubbed clean of anything resembling soil.

Miss McLaughlin, my plump and matronly kindergarten teacher, had wisely chosen the lowly (although to most kindergarteners inedible) radish as a fast and infallible germinator, in order to introduce her noisy, elbowing, poking, whispering, and giggling charges to the quiet miracle of germination. I tamped the disrupted surface of the soil in my waxy milk carton, watered again, and watched in awe a few days later as the fat cotyledons rose up quickly from the dark dirt. My radishes grew; I watered and watched over them and had no requirements of them. I wished to be friends with them. They soon tumbled over the sides of the container in etiolated glory. I never ate them.

This early success gave way to other trials—I prepared another milk carton and planted one of the brown, teardrop-shaped seeds extracted from an apple core and, by its side, one of the slick, tough-membraned seeds of an orange. “Those seeds won’t grow,” said my older and wiser brother, his arms folded across his chest. He knew that proper seeds came from a seed packet, not from fruits in a kitchen. My big sister, with a shake of her blonde pigtails, asserted, “Oranges don’t grow in Iowa.”

Always the optimist, I watered and waited (a long time, as I recall), daily climbing up on the counter and craning my neck toward the back of the sink. Eventually, my attention wavered and the container dried somewhat, but evidently this was just what was needed. One Sunday morning, I again checked the crumbling milk carton, and my squeal of delight brought both brother and sister (all sageness and dignity forgotten) tripping over each other, running from the next room. I can still see the way their jaws dropped when I pointed out the unlikely spectacle—the two seedlings emerging in cadence, side by side. The identity of the seedlings was clearly defined by their seed coats borne up like shining helmets, soon thrown off as the leaves unfolded to the light.

This experience engendered in my inner being an undying faith in seeds. I learned that if I created the right conditions of sun, soil, and water and planted the seeds carefully, just beneath the surface, tamped them in firmly, and kept them evenly moist, then eventually I would surely be rewarded. I never forgot these early successes, and never lost the excitement felt when seedlings push through the dark earth.

Of course, my brother and sister were right, in a way. Oranges and apples are not usually grown from seed, and my little seedlings never amounted to much. For all of us, experiments like this yield information, and this is one way that we progress in our knowledge. Besides, planting seeds was so much fun that I could not stop.

Advantages of cultivating from seed. After a lifetime of propagating plants, I have found that cultivating from seed is the most useful and effective method. Plants grown from seed produce a robust root structure. In general, seed-grown plants are better than those produced by cuttings, because plants grown from seed produce more entire and deeply seated roots and are thus more resistant to crown rot. Seed-grown plants demonstrate improved vigor, stature, yield, and longevity. Growing from seed also improves genetic diversity, as each individual is genetically distinct, unlike plants grown from cuttings, which are clones. Therefore, plants grown from seed will give a diverse population, demonstrating resilience in the face of environmental challenges and more likely to accommodate (sometimes over the course of several generations) to conditions in the domestic garden.

Variations in seed sowing strategies. The ideal technique for successfully sowing seeds varies according to the species being planted. Some large seeds, such as nasturtiums, are best sown very deeply. However, peas are large, too, and they do best when sown very shallowly. Plants in the Lobelia family produce very tiny seeds that are best strewn on the surface of the soil. Artemisia species prefer to germinate in the light, while celandine germinates best in the shade. Some seeds, such as pagoda tree, have a very hard seed coat (testa) and must absolutely be nicked with a knife or rubbed on sandpaper before planting. Others, such as curry leaf tree, have no testa at all. In this case, the challenge is to keep the seed from dehydrating, and therefore the seed does not withstand dry storage and must be sown immediately when ripe.

Rates of germination response. Some seeds, such as carob tree, germinate quickly in warm soil; others, such as ginseng, germinate slowly in cool soil. Some seeds, such as many in the lily family, require the passage of several seasons before germination is possible. They demonstrate double-dormancy, germinating usually in the spring of the second year. Two-phase germinators are plants that make a root in the first year and aerial parts in the second year. Trillium seeds exhibit both double-dormancy and two-phase germination, so it is not unusual for them to show their first leaf in the spring of the third year.

Longevity of seeds. Some seeds germinate best when they are very recent, such as coltsfoot and valerian, which have short-lived seed. Others give their highest germination after being aged for a year or more, such as cucumber and Hopi tobacco.

Many seeds are capable of remaining viable for extended periods of time. Experiments at the Michigan Agricultural College that began in the fall of 1885 have demonstrated that dry-stored seeds of evening primrose and yellow dock can remain viable for up to 80 years. Seeds of mullein can lie dormant in the ground for decades and germinate joyfully as soon as the soil is tilled and the sunlight awakens them. Seeds of the lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) have been shown to give 100% germination after 237 years of storage in moist peat.

The importance of rhizobia and mycorrhizae. Seeds of plants with nodulated roots, such as: astragalus, peas, beans, clovers, and indigos, germinate and grow most vigorously in soils where the nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria known as rhizobia are active. Soils that have been previously cover-cropped are sure to be already teeming with rhizobia. However, if seeds of this sort are to be sown in new potting soil or in a garden where legumes have not previously been grown, then it makes sense to pre-inoculate the seed. Rhizobium inoculant is commonly available through nursery supply outlets. Inoculating the seed before planting will create the proper conditions for desirable rhizobial symbiosis.

Furthermore, it is becoming increasingly clear that most plants develop symbiotic relationships with arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. The fungi enhance photosynthesis and water and nutrient uptake for the plants in exchange for plant-derived carbon and sugars. It doesn’t matter how rich the soil is, if the right endomycorrhizae are not present, the plant will not prosper. Plants sequester the types of mycorrhizae that are most relevant to them. The symbiosis develops as both plants and fungi mature. Get the process started by inoculating the soil around seedlings with soil taken from the root zone of healthy, mature plants of the same species. If this is not possible, then use live organic compost and mulch with straw. The plants will do the rest.

Gibberellic acid dependency. Seeds of certain plants will germinate and grow best in a medium where high concentrations of the plant hormone gibberellic acid are present. This growth hormone is formed by the breakdown of fungi in the soil. Therefore, it is very important to use decomposed leaves or woody debris in the potting soil when planting these seeds. Ephedra, bloodroot, datura, pulsatilla, and butcher’s broom are examples of plants that require an extra helping of gibberellic acid to enhance germination.

Unlocking the secrets of germination is one of the most challenging, yet rewarding, tasks that a seedsperson can engage. Gaining an understanding of the personal needs of each plant is usually knowledge bought with years of hard work—mainly “tions,” like cogitation, experimentation, and observation. Then again, as the following two stories illustrate, the best methodology is sometimes discovered through serendipitous circumstances.

Stories of serendipity. More than once, I tried growing skunk cabbage by planting the newly harvested seeds in moist flats in the shadehouse. I never got very good results—a sprout or two after a year or two was the best I could expect. Then, I stashed some skunk cabbage seed in a plastic bag of moist coir in the fridge and left it (then forgot it) on a low shelf for a good two years. This reveals how often I clean the refrigerator! Eventually, I rediscovered the bag, now a plasticized lump of mold, and thinking that I would compost it later, tossed it into an open box in the seed room. There it sat, at 60°F in the dark, for a couple more weeks. One morning, as the light from the one northern window filtered into the seed room and illuminated the box, an out-of-place greenness caught my eye. It was the developing leaves of the skunk cabbage seeds, transformed into pointy-leaved seedlings, trying to pierce their way out of the bag! I could only conclude that the long period of anaerobic curing, despite the presence of mold, was just what was needed to develop the embryo to the point where full germination was possible!

Another time I was experimenting with planting cilantro (Coriandrum sativum) in trays in the greenhouse at different times of year, trying to discover when best to sow it for optimal germination. One of these attempts was made in the late summer, and the seeds simply refused to germinate. After awhile I concluded that the seed was dead, and with disgust threw all the soil from the barren tray out onto the compost pile. A few cool nights and bright days went by, and one morning, in passing the compost pile, I noticed a green fuzz. On closer inspection, I discovered that this was composed of hundreds of beautiful cilantro seedlings germinating in unison, their pointy leaves lifted jauntily to the sun. “Well,” I mused. “Next time I’ll direct-seed the cilantro!”

The story really has no end. It is like navigating an endless cave of ignorance, illuminated at intervals by candles of realization. Eventually I learned that cilantro, like all members of the carrot family, is a 2-seeded syncarp. If you gently rub the globular seeds between two boards, then each globe will break apart into two half-moon-shaped seeds. Once this is done, then the seeds can readily imbibe water, and germination is much enhanced. So I was focused on time and temperature when the real issue was seed preparation. Light another candle, take another step, enjoy the process, and watch out for hidden pitfalls!

SEE THE VIDEO IN THE HERBARIUM!

Members of The Herbarium can join Richo Cech of Strictly Medicinal Seeds in his greenhouse for a lively discussion on seed starting topics from potting soil, seed scarification, and cold conditioning to gibberellic acid, mycorrhizal symbiosis, and potting up! You’ll find this engaging and instructive Starting Herbs from Seed video in The Herbarium.

Interested but not yet a member of The Herbarium? Get access today with a 3 day trial for only $3!

The Herbarium is our ever-expanding, illuminating virtual collection of over 200 (and counting!) searchable monographs, unique intensive short courses on focused topics, and numerous articles, videos, ebooks, podcasts, and helpful downloadable resources. The Herbarium is crafted to help you learn and grow in your herbal journey!

Learn more and sign up for The Herbarium here.

Get a copy of Richo’s book, Growing Plant Medicine, via his website here.