Sheltering with Valerian

In January, I wrote about medicinal herbs in England use during World War II, and this month I would like to follow-up up with a bit more information about one of the most important plants that were collected and used, valerian. England needed effective medicines to supply the home front, so the Vegetable Drugs Committee at the Royal Botanic Gardens (Kew) organized a collection scheme in which hedgerows and other natural sites were for combed for useful plants.

Plants Used for Physical Ailments in World War II

Plants were categorized by priority of need; the most essential plants included diuretics (broom, Cytisus scopiarius, and foxglove, Digitalis purpurea—now fallen out of favor because of concerns about toxicity), vermifuges (male fern, Dryopteris felix-mas), and treatments for gout (autumn crocus, Colchicum autumnale) and influenza (elder, Sambucus nigra).

These plants certainly provided relief for common physical ailments, but what about the psychological aspects of war? Women carried the major responsibility for war work, child care, cookery, rationing, and household tasks. Moreover, England experienced intense nocturnal bombing raids, when the only option was to collect family members, seek shelter, and hope against a direct attack.

British physicians predicted that with the onset of aerial bombing millions would suffer from psychological trauma, and there were certainly frayed nerves and fear during these trying times. Given the sustained attacks against England that began in September 1940, it is not surprising that the Vegetable Drug Committee included valerian (Valeriana officinalis), long valued for its sedative properties, on the list of most essential plants for collection and use.

Valerian for Psychological Support

With bombing a reality, newspapers and women’s magazines suggested coping strategies for comfort and safety. Shops advertised siren suits for both children and adults; these were one piece jumpsuits that could be zipped up quickly over pajamas, popularized by Winston Churchill who wore his own pin-striped siren suit to meet with heads of state.

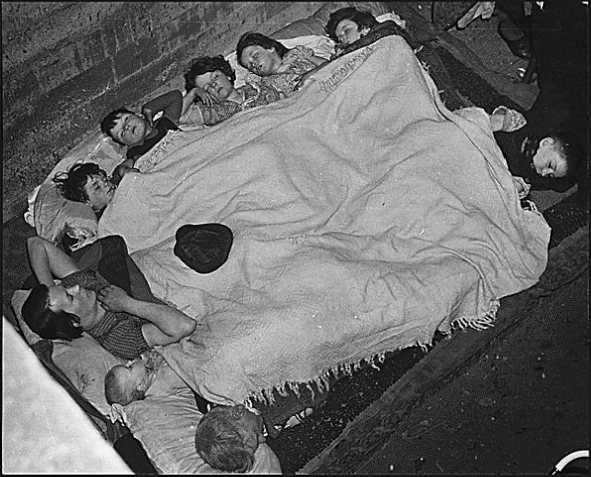

Because excavated shelters were often damp and cold, women were advised to pack blankets, eiderdowns, hot water bottles, warm drinks, and sandwiches for nights spent keeping safe from bombs. Columnists such as Mary Rose, who penned “Making the best of a ‘Sheltered’ Life” in the Manchester Daily Sketch, recommended personal items to improve spirits and counter fear. Small luxuries included face creams and powders, cologne, smelling salts, and “nerve tablets”—which most likely contained valerian.

Public domain photograph, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

The use of valerian in war time was nothing new. In A Modern Herbal (1931), Maud Grieve described valerian as a “powerful nervine, stimulant, carminative, and anti-spasmodic.” She noted the use of valerian during World War I:

“The drug allays pain and promotes sleep. It is of especial use and benefit to those suffering from nervous overstrain…During the recent War, when air-raids were a serious strain on the nerves of civilian men and women, valerian…proved wonderfully efficacious, preventing or minimizing serious results.”

Valerian was also used to treat soldiers who suffered psychological effects after fighting on the front lines; it was administered as a tincture to shell-shocked infantrymen during both world wars.

Ancient Greeks and Romans understood the medicinal properties of valerian, using it to calm stomachs and improve digestion. Dioscorides recommended the herb for heart palpitations, Galen mentioned it for insomnia, and Arabs deployed it to control aggression. In fact, the generic name Valerian is likely derived from the Latin verb valere, which commands us to be strong, while the specific epithet officinalis refers to the medical properties of the species.

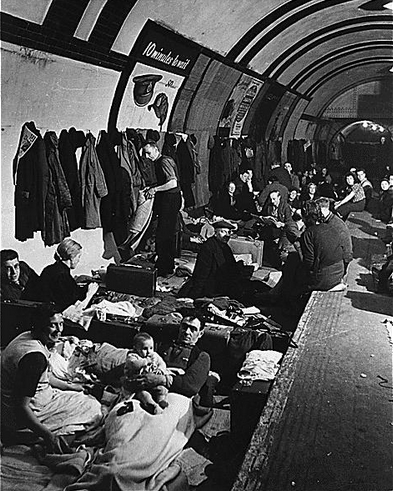

Public domain photograph, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

Valerian appeared in editions of the U.S. Pharmacopoeia between 1820 and 1930, becoming a popular remedy for “vapors,” cramps, anxiety, headaches, high blood pressure, nervous complaints, and even naughty behavior in children.

Valerian Use Today

Active principles are concentrated in the aromatic rhizomes, robust underground stems that often colonize old garden sites. Despite its long history of use, the mode of action of valerian is poorly understood, but it is based on a complex chemistry; active principles include various valepotriates, sesquiterpenes, and several aromatic oils. The National Institutes of Health (NIH) valerian fact sheet speculates that its efficacy may result from synergy among its chemical components. It also summarizes the positive outcomes of various studies on valerian as an herb for insomnia.

In the U.S., valerian is currently sold as a dietary supplement that “promotes rest and relaxation,” “promotes relaxation in individuals leading a hectic lifestyle,” “helps support restful sleep”—without specific medical claims. As with all herbs, valerian should be treated with respect; alcoholic tinctures may be more powerful than aqueous preparations, and side effects including headaches, dizziness, and gastro-intestinal upset may occur—regardless of whether valerian is used as capsules, tablets, extracts, or teas.

Valerian During Trying Times

Can we imagine today dealing with nightly bombing raids? In fact, the English coped for years—beginning in the fall of 1940 and continuing through the early spring of 1945. In cities, there were communal shelters such as the underground tube stations that were deep below street level; many flocked to these sites at night to catch a few hours of sleep before another day of war work, ration queues, and making do.

Fortunate people returned to their homes to find them undamaged, or at least still standing. Those with gardens often installed their own simple Anderson shelters several feet from the house. These were named for Sir John Anderson; at the time, he served the government as Lord Privy Seal, with special responsibility for sorting out air-raid precautions before the declaration of war in September 1939.

A shelter for a family of six comprised fourteen corrugated sheets of galvanized steel, with end pieces and gas-proof curtains, (these were hung in the event of a mustard gas attack, which fortunately never occurred). Correct installation required excavation to a depth of four feet, with 15 inches of displaced garden soil covering the arched roof.

There was early concern that German airplanes would strafe sites with freshly overturned soil, so seeds were sown in haste to provide camouflage. In particular, marrows (various squashes) seemed to flourish in the warmth and good drainage provided by garden soil mounded over corrugated metal. But I also wonder if some Anderson shelters might have been banked by valerian; Anglo-Saxons ate the leaves as a “sallet” plant, and the species is well known for colonizing a garden corner. Either way, many who descended into shelters at night carried their valerian with them.

As I continue to discover and document the botany of World War II, I often contemplate English endurance: courage and defiance in the face of fear and destruction. Valerian served them well, as an herb that eased frayed nerves during trying times.

Judith Sumner is a botanist and author of The Natural History of Medicinal Plants and American Household Botany: A History of Useful Plants, 1620-1900. Learn more about Judith on her website.