Adding Yarrow To Your Materia Medica

Yarrow grows freely in my gardens and I encourage it to do so, as much for its beauty as its beneficial uses. While the blooms have just gone by in my garden, the harvest is drying on the herb rack and macerating into a potent tincture in the herb cupboard. And while yarrow has long been a favored herb for me, I feel that there is more I have yet to understand about it—so I return to my materia medica and add a few more notes and observations from the harvest and spend some time browsing my herb books for more insights.

Getting Started with Yarrow

One of the first things I do when researching an herb is to dig into historical texts and learn how the plant has been used traditionally. A Modern Herbal by Margaret Grieve was first published in 1931 and details the plant description, parts used, actions, uses, and preparations (keep in mind this was written almost a century ago and cross-referencing with updated safety info is important). The information in this book has been uploaded here as an alphabetized plant list.

And while there are many good herbal books I consider go-to references, I often start with Matthew Wood’s books because he gives such a good picture of the herbs from an energetic perspective. This allows me to get my head around an herb in a way that feels more intuitive and relatable.

Two Important Uses for Yarrow

When preparing for a recent plant walk, I tried to narrow down the information on each herb’s uses in a way that would inform my students without overwhelming them. I wanted them to walk away with one or two nuggets of information on yarrow that would really help inform their use of the plant. And while yarrow is certainly helpful as a digestive bitter, as an antimicrobial and diuretic for the urinary tract, and as an antispasmodic for painful menstrual cramping, it is yarrow’s multi-varied use during colds and fever and its long history of use for wounds that rose to the top of my list.

1. Yarrow for Wounds

Many of us have heard that yarrow takes its name Achillea from the Greek hero Achilles, who used yarrow for the wounds of his friends on the battlefield (Berger, 1998). Judging by its common names—soldiers’ woundwort, staunch weed, nosebleed, woundwort, and carpenter’s weed—Achilles isn’t the only one who has used yarrow for wounds throughout history. Additionally, in the Native American pharmacopeia, the Bella Coola have traditionally used it for boils, the Cherokee for piles, the Cheyenne as a hemostatic, the Crow as a burn dressing, the Kutenai and Lakota for wounds and sores, the Menominee for swellings, sores, and rashes, and the Paiute for swellings, sores, and cuts (Moerman, 1998).

As a hemostatic or styptic, yarrow aids clotting to arrest the flow of blood from wounds, while its antibacterial and anti-inflammatory actions help decrease the chance of infection and support wound healing (Hoffmann, 2003; Wood, 2009; Mohammadhosseini et al., 2017). As Matthew Wood (2009) describes, yarrow’s effectiveness for wounds, bruising, blood clotting, and hemorrhage is related to its ability to regulate the flow of blood to and from the skin’s surface through a variety of mechanisms. Yarrow can be used as a poultice of fresh leaves, a soak of yarrow infusion or a compress, a pinch of dried powder, or a squirt of yarrow extract, ideally after thoroughly cleansing any open wounds.

2. Yarrow for Colds and Fever

Its ability to regulate blood flow coupled with its diaphoretic action leads herbalist Matthew Wood to call yarrow a “master of fever” due to its ability to move blood toward the skin or the core of the body as needed, thus regulating heat (Wood, 2009). In this way, yarrow can be either warming or cooling and is a prime example of an herb with dual energetics that, at first glance, might seem contradictory. As a diaphoretic, yarrow stimulates circulation toward the periphery of the body, opens pores, and stimulates sweating to allow cooling—hot tea is ideal for this. Additionally, yarrow’s volatile oils help promote the healthy flow and elimination of mucus (anti-catarrhal), especially from the sinuses, and its anti-inflammatory and astringent nature soothes sinus tissue by reducing swelling.

Yarrow Safety

As an Asteraceae family plant, sensitive individuals may experience an allergic reaction to yarrow. Herbalists generally caution against the use of yarrow during pregnancy (Hoffmann, 2003; Wood, 2009; Mills & Bone, 2005).

Identifying Yarrow Correctly

One of the most important aspects of working with yarrow is correct identification, particularly if you are wild-harvesting as there are several white-flowered plants that bloom at the same time.

Yarrow is often confused with wild carrot (Daucus carota), an edible and medicinal plant also known as Queen Anne’s lace. More concerning is confusing yarrow or Queen Anne’s lace with poison hemlock, which causes central nervous system depression and respiratory failure that can lead to death (Konca et al., 2014). Once you get to know yarrow, though, it is pretty recognizable in comparison to these two plants, which actually resemble one another more than they resemble yarrow.

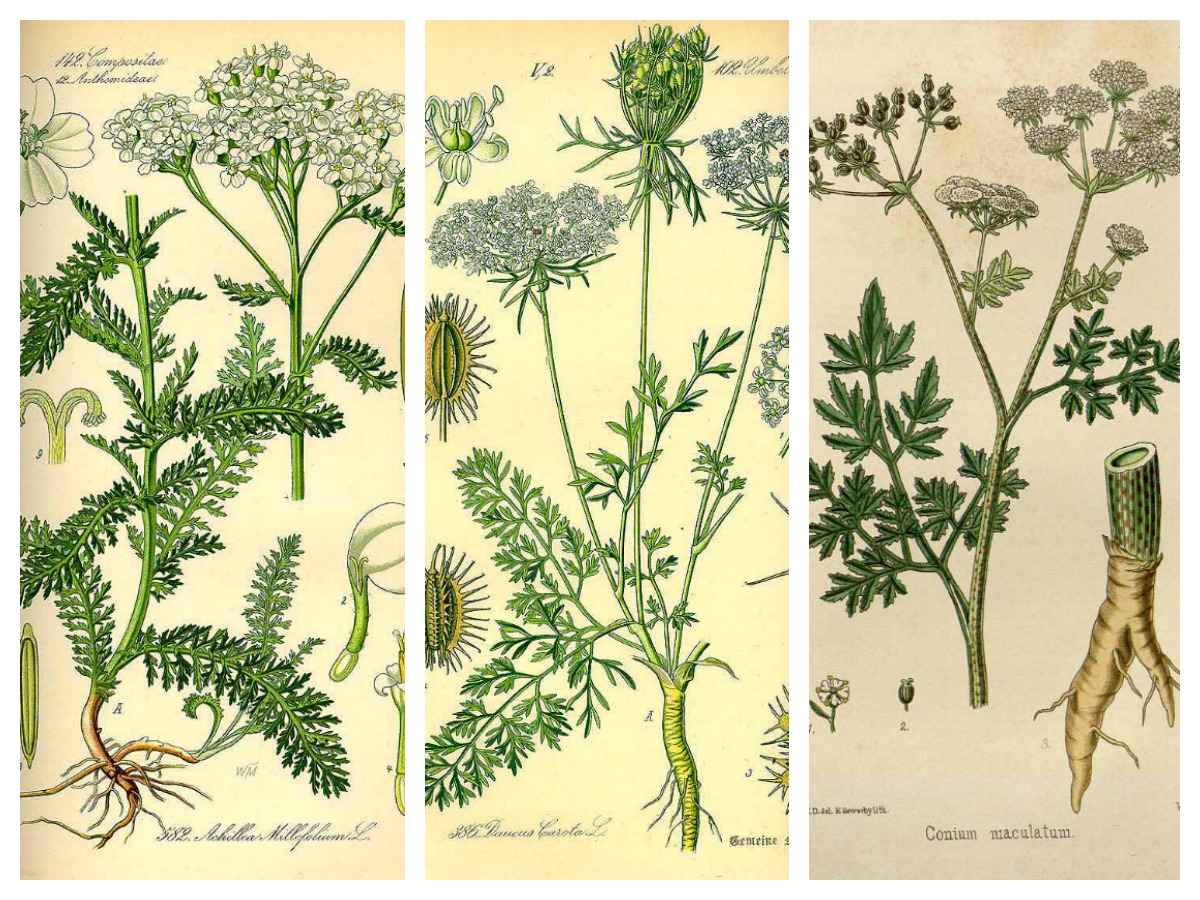

| Botanical Characteristics of Yarrow and Two Other White-Flowered Plants | |||

| Yarrow | Queen Anne’s Lace | Poison Hemlock | |

| Family | Asteraceae | Apiaceae | Apiaceae |

| Botanical Name | Achillea millefolium | Daucus carota | Conium maculatum |

| Plant | 1-3 feet tall | 2-4 feet tall | 6-10 feet tall |

| Leaves | Finely divided, attached directly to stem | Finely divided (less so than yarrow), feathery, covered with short hairs. Look like carrot tops. | Divided and fern-like, shiny, no hairs. Arranged alternately on the stem. Musty, disagreeable smell. |

| Stalk | Slightly hairy, solid, stout, branching. | Hairy, solid, stout, branching. | Smooth (hairless), hollow, purple splotches, branching. White “bloom” on the stalk (like white powder) leaves a residue. |

| Flower | Flat-topped clusters of flowers on branching stems. | A white lacy umbrella of flowers on top of each stem, often a single purple/red flower in the center, umbel densely arranged. | Several white lacy umbrella-like clusters of flowers off each stem, umbel loosely arranged so it looks sparser and individual “umbrellas” are more distinct. |

| Root | Spreading rhizomes. | Cream-colored taproot, woody, hairy, smells like carrots. | White fleshy taproot, smooth, purple mottling. Smells like carrots/parsnips. |

| Compiled from Hanson (2011) and Thayer (2010). | |||

Start Building your Materia Medica with these free pages!

Looking for great resources for your own materia medica research? Check out The Herbarium, our online database of plant monographs!

REFERENCES

Berger, J. (1998). Herbal rituals. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

Hanson, W. (2011). Hanson’s Northwest native plant database. http://www.nwplants.com/information/white_flowers/white_comparison.html

Hoffmann, D. (2003). Medical herbalism. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

Konca, C., Kahramaner, Z., Bosnak, M., & Kocamaz, H. (2014). Hemlock (Conium Maculatum) poisoning in a child. Turkish Journal of Emergency Medicine, 14(1), 34–36. http://doi.org/10.5505/1304.7361.2013.23500

Mills, S. & Bone, K. (2005). The essential guide to herbal safety. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Moerman, D. (1998). Native American ethnobotany. Portland, OR: Timber Arts Press.

Mohammadhosseini, M., Sarker, S., & Akbarzadeh, A. (2017). Chemical composition of the essential oils and extracts of Achillea species and their biological activities: A review. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 199, 257-315. 10.1016/j.jep.2017.02.010.

Thayer, S. (2010). Nature’s garden: A guide to identifying, harvesting, and preparing edible wild plants. Birchwood, WI: Forager’s Harvest Press.

Wood, M. (2009). The earthwise herbal: A complete guide to new world medicinal plants. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books.