How to Grow Echinacea

Echinacea (Echinacea spp.) is an herbaceous, flowering perennial native to North America. This plant has a long history of use and is still a popular herbal supplement today. Unfortunately, over-harvesting and the destruction of its native habitat have affected wild echinacea populations, and it’s now included on United Plant Savers’ list of “at-risk” plants. Learning how to grow echinacea is an ecologically responsible decision. Plus, it will help you develop an even deeper relationship with a fantastic herbal ally.

Echinacea, also called coneflower or purple coneflower, is a prickly beauty of the Asteraceae family. Its compound flowers consist of pink or purple sterile ray flowers, or petals, and a tough spiny mound of fertile disk flowers in the center (Hobbs, 1994). A few wild species are even light purplish white (E. pallida) or yellow (E. paradoxa). The foliage is dark green, sturdy, and rough. It blooms in summer, and the striking flowers attract all kinds of pollinators to the garden. There are three different types of echinacea grown for herbal preparation: Echinacea angustifolia, E. purpurea, and E. pallida (Foster, 2009). While these three types of echinacea are used in herbal formulation interchangeably, and often in conjunction, E. angustifolia, or E. purpurea are the species that most herbalists prefer.

Echinacea is a popular immune support herb. People all over the world use it to shorten the duration and intensity of symptoms related to colds and the flu. The constituent profile of echinacea seems to upregulate the body’s ability to rid itself of harmful intruders through a process called phagocytosis. Both the aerial portions as well as the roots have this action in the body (Bone, 1997).

Choosing the Right Spot

When inviting a wild plant into your garden, consider where it lives in nature. This study helps to understand what conditions the gardener must cultivate to allow the plant to feel at home, and ultimately thrive (Cech & Cech, 2009). Echinacea grows in wide-open spaces, like prairies or fields, in areas that the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) has labeled as Hardiness Zones 3-9 (Martin, 2020). This observation leads to the understanding that echinacea wants to be in full sun in its natural range. In sunnier western states, choose a spot where the plant is shaded for a portion of the day (Cornell University, 2006).

Any of these species will grow in the ground or a pot provided that the pot is large enough to accommodate the broad root system. E. angustifolia and E. pallida both prefer a well-drained soil of poorer quality. E. purpurea likes to sink its roots into a rich, moist, loamy soil (Hartung, 2011). Consider which environment is easier to replicate in your space when buying seeds or starters.

There are many decorative cultivars of echinacea that are beautiful to behold; however, only the three discussed in this article are appropriate for herbal preparation. Verify the species when purchasing seeds and starters. This may take some detective work especially if presented with only commonly stocked nursery cultivars. For example, Echinancea magnus (or E. purpurea x Magnus) is one cultivar of E. purpurea that may be the closest you can find to a wild type in many nurseries. This one is useful! Companies dedicated to cultivating traditional or heirloom varieties of seeds and starters are the best choice.

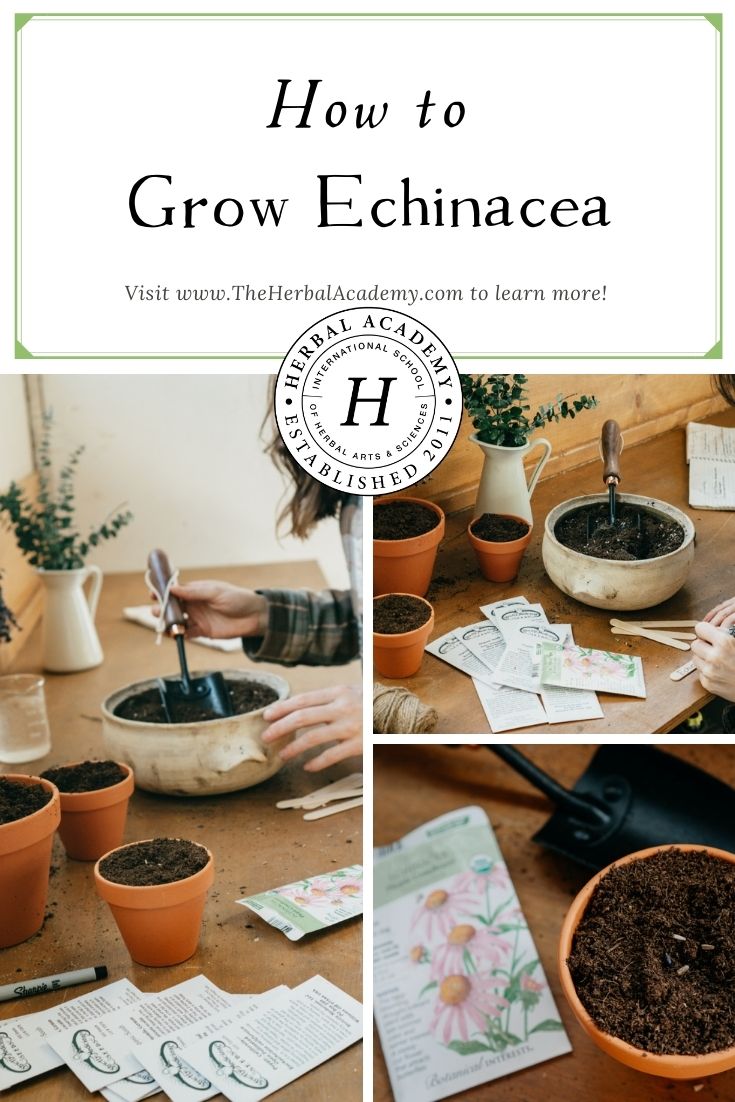

Seeds and Transplants

Learning how to grow echinacea is an exercise in patience, and growing it from seed will take forethought as well. To ensure successful germination, buy echinacea seeds in the fall. Place them in a labeled plastic baggie with a few drops of water, and place it in the freezer for three months. Remove the seeds from the freezer once a month, allow them to thaw on the counter, and then place them back in the freezer. This process is called “ cold-moist stratification” and it mimics the long cold winter these seeds would experience in nature (Hartung, 2011). For more on this topic, see “Starting Your Own Seeds: Time for Cold Stratification.”

Sow seeds directly outdoors after the soil temperature reaches the mid-sixties (The Old Farmer’s Almanac, n.d.). Or, for best results, start seeds indoors a month before the last freeze in your area. (To find your average last frost date, type your Zip code in here.)

Whether you start your seeds indoors or purchase established starts, they should be transplanted outdoors when the threat of frost has passed. Before you transplant them, however, it’s best to harden them off. Hardening off is an important process for preventing shock when introducing a plant to its new home. Direct sunlight, wind, and chilly temperatures can be rough for a seedling that’s spent its entire lift sheltered indoors. To harden them off, take the plant outside each morning and bring it back inside each night for a week, starting it off in the shade, and gradually increasing the amount of sun exposure the plant gets each day (University of Maryland, n.d.). Keep the soil moist throughout the process to prevent wilt.

Dig in!

If cultivating your echinacea in a pot, choose a two or three-gallon container with holes in the bottom. Line the bottom with gravel to allow for drainage, and fill halfway with soil. Gently loosen the roots, and place the plant so the root ball is an inch below the container’s rim. Slowly add dirt around the sides, pressing it down as you go, covering the root ball entirely (The Old Farmer’s Almanac, n.d.). Give it a nice, thorough watering when you’re done.

If planting in the earth, dig the hole twice the size of the root ball in width and depth. Gently loosen the roots, and place the starter in the hole. Add dirt around the sides evenly, tamping down as you go. After the plant is in its new home, water thoroughly.

A perennial, echinacea retreats to its roots, rests for the winter, and then reappears in the same spot the following spring (USDA, n.d.). Mark echinacea’s spot in the garden with a stone or sign. Knowing the placement of perennials helps to avoid disturbance of the roots when working and planting the beds.

Maintaining Your Echinacea Patch

E. pallida and E. angustifolia will only require light watering on a regular basis. E. purpurea requires moderate watering to keep the soil moist (Hartung, 2011).

Echinacea self seeds, so it is unnecessary to collect seeds at the end of each growth cycle (Martin, 2020). Leaving the seeds in the seed head allows nature to do the work of overwintering them for you. Self-seeding means echinacea can quickly spread and take up more space than intended (Cornell University, 2006). Keep this spreading behavior in check by weeding out new seedlings regularly or co-plant echinacea with other competitive species, such as mint (Mentha x piperita) and yarrow (Achillea millefolium). To prevent self-seeding, snip the flowers from the plant when they lose their luster. This will also encourage continuous blooming (Plant Index, n.d.).

Beyond watering, the only regular maintenance echinacea requires is trimming and cleaning last year’s plant debris when green growth appears each spring. This might seem trivial but may reduce the amount of ‘rusts’ or natural plant pathogens that can slightly affect echinacea’s health, particularly in wet climates.

Root division can be done about every 4 years to keep the plants healthy (Plant Index, n.d.), however selectively harvesting and dividing the roots as you go will achieve this effect. Roots also need to grow and mature for at least 4 years before harvesting (Chevallier, 2000). The root division and harvesting processes are one and the same.

Harvesting Echinacea’s Above Ground Parts

The leaves, stems, and blooms are the aboveground parts of the plant. In the spring and summer, the energy of the plant is concentrated above ground in the effort to produce foliage and flowers, making it the ideal time to collect these parts of the plant. Harvest the outer leaves and fully bloomed flowers by clipping the stalk down at the root crown.

If the plant hasn’t flowered yet, you can still collect the outer leaves of the plant for use. This plant grows up from the center, so if you take the inner leaves, before the plant flowers you can stunt the growth and flowering of the plant. Leavin the center of the plant intact allows the plant to continually regenerate.

Begin to harvest the aerial parts of echinacea in the second year of the plant and beyond (Hartung, 2011). Allowing uninhibited growth the first year helps the plant to establish itself without becoming stressed by harvesting. This also allows the plant to self-seed over a cold winter and expand its populations before you begin to harvest any for use. Harvesting the aerial parts of echinacea is less invasive and stressful to the plant, and the plant can withstand continual harvesting after it has reached its second year.

The aerial portions of the plant can be juiced and preserved with alcohol to create a succus. This succus can be administered at the first signs of a cold or flu to decrease the severity and duration of symptoms. There are companies that market this kind of echinacea supplement in Germany, where this preparation and delivery have received much attention in clinical studies (American Botanical Council, 2000).

To preserve the aerial portions of echinacea for later use, lay them out to dry in an area with good air circulation and low light. Lining a cardboard flat with paper towels will make a fine surface for plant drying. Flip and rotate the aerial parts on your drying surface throughout the process to ensure that they dry evenly and to prevent mold from forming. The leaves should dry in about a week, but the densely clustered flower heads may take a couple of weeks or more to fully dry out.

Once the aerial portions of the plant are dry, store them in an airtight container away from direct sunlight, labeled with the common and binomial name. Store the aerial portions and the roots in your apothecary separately; they can always be mixed for preparation, but they may benefit from different extraction methods. For example, the aerial portion of plants are more delicate and benefit from extraction by infusion, and the tougher roots generally benefit from extraction by decoction. Aerial portions of echinacea are also used to make herbal honeys, lozenges, infusions, tinctures, syrups, and salves (Hartung, 2011).

Harvesting and Dividing Echinacea Roots

Dig up echinacea in the fall, when the energy of the plant is in the roots. You can tell that the energy of the plant has moved when the above-ground portion turns withered and lifeless, a stage called senescence. After unearthing the roots, shake off excess soil, and remove the aerial parts from the root crown. Turn the root cluster to the side, and using a sharp knife or pruners divide the root cluster into smaller sections. Any cluster used for replanting should have at least two root clumps attached to the crown (Hartung, 2011).

Through the process of root division, there is the opportunity to increase your echinacea population by replanting multiple root divisions, instead of just one. To replant, place root clusters in the ground, cover, and keep the soil evenly moist. The portion that is not replanted is your harvest to use in herbal preparations. Before using echinacea, it is important to wash the roots thoroughly.

Echinacea roots are used fresh or dried and stored for later use. To dry, cut clean roots into thin strips using a sharp knife. Lay the strips out, in a single layer, on a screen or a surface lined with clean tea towels, away from light. Bring a fan into the room to increase airflow. Flip the pieces of root every few days until they are dry. Roots can take a couple of weeks to dry completely, and the strips should become brittle. (Hartung, 2011)

After all the moisture is gone from the roots, store them in a cool dark place. Always choose an airtight container for storing herbs. Mark the container with the common and binomial name of the herb, and the year of harvest. These roots are used to make teas, syrups, tinctures, lozenges, and honeys (Green, 2002).

In Closing,

Beyond the ecological and preservationist reasons for learning how to grow echinacea, there are also energetic reasons for cultivating your own herbal resources. From seed to final preparation, you create and hold the energetic space in which you interact with the plant. Cultivation teaches us how to give before we take. When we cultivate our own plants, we create a bond of reciprocity with our herbal allies.

RESOURCES

American Botanical Council. (2000). Echinacea purpurea root. Herbal Medicine: Expanded Commission E. Retrieved from http://cms.herbalgram.org/expandedE/EchinaceaPurpurearoot.html

Bone, K. (1997). Echinacea: What makes it work? [PDF]. http://www.anaturalhealingcenter.com/documents/Thorne/articles/Echinaeca.pdf

Cech, R., & Cech, S. (2009). The medicinal herb grower v. 1: A guide for cultivating plants that heal. Williams, OR: Horizon Herbs.

Chevallier, A. (2000). Encyclopedia of herbal medicine: The definitive home reference guide to 550 key herbs with all their uses as remedies for common ailments). London, England: Dorling Kindersley.

Cornell University. (2006). Coneflower, purple [Growing Guide]. Retrieved from http://www.gardening.cornell.edu/homegardening/scene1d08.html

Foster, S. (2009). Echinacea monograph [Article]. Retrieved from http://www.stevenfoster.com/education/monograph/echinacea1.html

Green, J. (2002). The herbal medicine-makers’ handbook: A home manual. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press.

Hartung, T. (2011). Homegrown herbs: A complete guide to growing, using, and enjoying more than 100 herbs. North Adams, MA: Storey Pub.

Hobbs, C. (1994). Echinacea: A literature review; Botany, history, chemistry, pharmacology, toxicology, and clinical uses. HerbalGram the Journal of the American Botanical Council, (30) Retrieved from http://cms.herbalgram.org/herbalgram/issue30/article702.html?ts=1602021075

Martin, S. (2020). Echinacea – Americana in the Garden. The Garden Shed Newsletter, 6. [Newsletter] Retrieved from https://piedmontmastergardeners.org/article/echinacea-americana-in-the-garden/

The Old Farmer’s Almanac. (n.d.). Coneflowers. [Growing Guide] Retrieved from https://www.almanac.com/plant/coneflowers

University of California Marin Master Gardeners. (n.d.). Plant guide: Echinacea purpurea ‘big sky series’. [Database] Retrieved from http://marinmg.ucanr.edu/Choose_Plants/Plant_Guide/Plants_by_Type/?uid=30

University of Maryland Extension. (n.d.). Hardening Off Vegetable Seedlings. [Website] University of Maryland. Retrieved from https://extension.umd.edu/hgic/hardening-vegetable-seedlings

United States Department of Agriculture (n.d.). [Map of Echinacea pallida native habitat range]. PLANTS Database. Retrieved from https://plants.sc.egov.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=ECPA