Undercover Women: Historic Botanical Illustrators

In the modern age, the title of “artist” is an acceptable profession for both male and female persons, but it wasn’t always this way.

Historically, the art world was a male-dominated one. This was most likely due to the fact that men were considered the “breadwinners” of the family while women tended to more domestic tasks at home. This meant that men were better trained and educated in years past than most women.

While there are a lot of worthy male contributions to art, specifically in the field of botanical art, today, in celebration of International Women’s Day, we want to open your eyes to a few noteworthy historical women who made their mark on the art world as botanical illustrators during a time when it was less acceptable.

These women pushed through cultural, societal, and gendered walls to do what they loved, to support their family, and sometimes, simply to survive. While most of them led privileged lives in the eyes of many, they did break away from the traditional female roles of their time, which took considerable strength and determination.

3 Female Botanical Illustrators of the Past

Ch’en Shu (1660-1736)

Ch’en Shu was born in eastern China to an elite family of the gentry. At that time, most females were educated and instructed in matters that would help them later in their married life. However, some upper-class women were given the opportunity to receive an education, and Ch’en Shu chose this path rather than the typical female interests, strictly going against her mother’s wishes for a time. It is written that Ch’en Shu was a strong-minded child and was more interested in what her brothers were learning than learning about domestic skills.

Ch’en Shu’s father was a painter, and he doted upon her. This allowed her the opportunity to self-study painting as a young girl. She was also eventually taught to read and was educated in many classic books of the time.

Ch’en Shu later married and had a son, but after the early death of her husband, she was left to raise her son by herself. Not much is known about her life during this period, but in her son’s biography of her, he praises his mother’s virtue and her commitment to family and community as well as her artistic ability and how she used it to add to her family’s wealth and to teach future generations about art as well.

Ch’en Shu is considered the first female painter of the Qing dynasty as well as the first artist to introduce the Xiushui School painting style. She contributed many botanical illustrations during her lifetime, many of which are a part of the imperial collection and on display in both the Palace Museum in Beijing and the National Palace Museum in Taipei.

You can get an even more detailed look at Ch’en Shu’s life and story in the book, Flowering in the Shadows: Women in the History of Chinese and Japanese Painting.

Elizabeth Blackwell (1699-1758)

Elizabeth Blackwell was raised by an artist father and trained as an artist in Scotland, but her adult life wasn’t an easy one. She secretly married Alexander Blackwell when she was 27, and her husband had a knack for partaking in careers, like practicing as a physician and then later as a publisher, without the proper credentials.

His misadventures eventually landed him in debtor’s prison, and with no way of paying for his release, Elizabeth had to put her artistry skills to use to support her family and pay for her husband’s freedom – a rare predicament for females of that time.

At this time in history, there were no herbal materia medicas available in England for physicians to reference that contained both the medicinal qualities of plants and herbs as well as botanical illustrations so the plants could be identified. This led Elizabeth, along with her husband’s help, to create one in which she called, A Curious Herbal.

While Elizabeth was the botanical illustrator for the book, her imprisoned husband provided the scientific nomenclature and common names of the plants in various languages as well as information regarding what the plants could be used for.

Elizabeth studied and drew plants contained in the Chelsea Physic Gardens to include in the book. To save money she etched and engraved each image herself and then hand-colored them when they were printed. It was during this time, when she was working on the botanical illustration for the book, that both of her children died. Still, she continued on.

Creating this book with little to no money was not an easy task, but thankfully, she had many people come to her aid and help her along the way. Finally, after six long years of work, A Curious Herbal was finished. The book was popular with physicians of the time and, eventually, a second revised edition was published. With profits from the book, Elizabeth was able to pay off her husband’s debts.

Unfortunately, her husband did not change his ways after being released. He eventually was imprisoned again in Sweden, tried and sentenced for conspiracy, and was executed in 1747.

Not much is known about Elizabeth Blackwell’s life after her husband’s death, but her book, A Curious Herbal, continued to be printed and is considered a classic of botanical illustration. Carl Linnaeus even gave her the nickname Botanica Blackwellia, and there is a genus of plants named after her, Blackwellia of the class Dodecandria Pentagynia.

You can read even more about Elizabeth Blackwell’s story in the British Library and the Wiley Online Library.

Anne Kingsbury Wollistonecraft (1791-1828)

Anne Kingsbury Wollstonecraft was a North American botanist, naturalist, botanical illustrator, and women’s rights advocate. While not much is known about her early life, she is best known for her lost work of botanical illustrations as well as being the aunt of Frankenstein author, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley.

Anne was born and raised in New Hampshire, but after the death of her husband in 1817, she made a brave move to colonial Cuba where she studied the flora of the region. She published several articles about her botanical discoveries, but many of these were attributed to D’Anville, a pseudonym she often used when writing articles about women’s rights and the lack of education available to young girls in the United States during the colonial period.

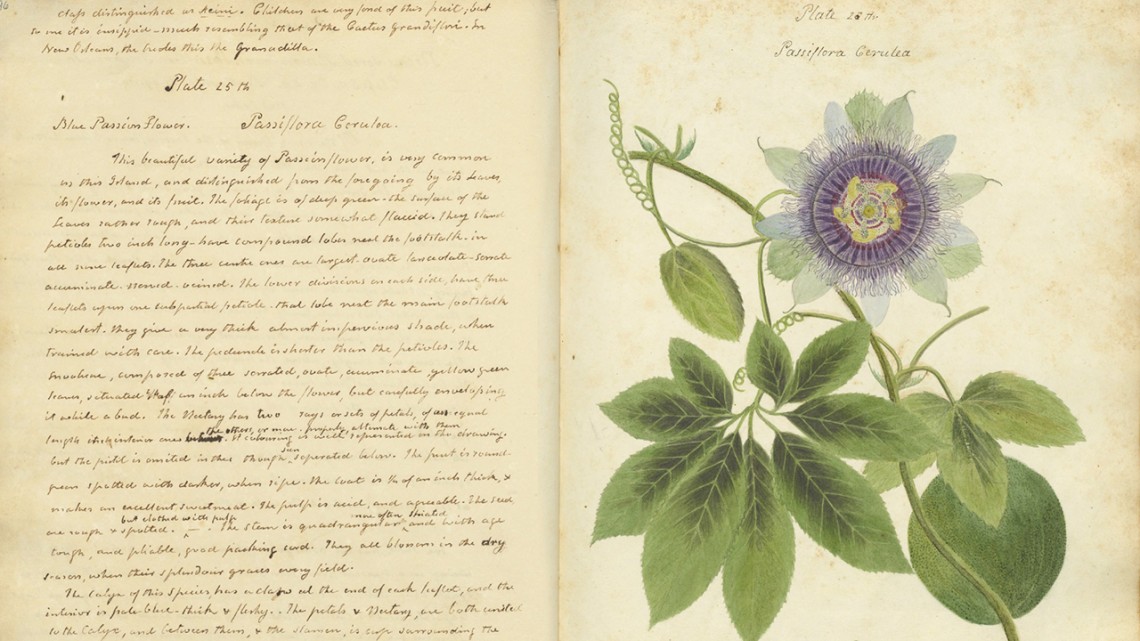

In addition to her botanical and women’s rights publications in various papers and magazines, she eventually created an extensive three-volume body of work called, Specimens of the Plants and Fruits of the Island of Cuba that included her watercolor botanical illustrations and descriptions of the plants of Cuba as well as their indigenous uses. It is believed to be one of the earliest documented records of Cuba’s plant life and contains 124 of the 145 botanical illustrations of Cuban plants documented at this point in history.

Anne sent the almost completed manuscript to her publisher, using her real name this time, but unfortunately died in 1828 before it was completed. The unfinished portion was never published and somehow went missing!

While there were mentions of a body of work about the plants of Cuba, no one had seen it until a descendant of Anne Kingsbury Wollstonecraft did some digging and eventually located it in 2018. The unpublished manuscript had been donated to the Cornell University Library and had been there for years. It was “lost” because early references to the book had misidentified Wollstonecraft’s name, therefore, the book was not associated with her due to that early error.

After it was discovered, it was digitized and properly attributed to her. Anne Kingsbury Wollstonecraft’s almost 200-year “lost work” is now available on the HathiTrust Digital Library courtesy of Cornell University.

You can read more about Anne’s “lost book” on the Atlas Obscura website as well as in an article in National Geographic magazine.

Are You Interested in Learning More About Botanical Illustration?

We hope that the stories of these three historic women botanical illustrators have inspired you in some way.

If you are interested in learning more about botanical illustration, we’d like to invite you to join our new Botanical Drawing for Herbalists course.

Now, before you ask, no, this course isn’t only for artists — it’s for herbalists! If you dream of filling your materia medica with beautiful, accurate botanical illustrations, then the Botanical Drawing for Herbalists course is for you!

This new Botanical Drawing mini-course includes an introduction to botany and plant parts, more than a dozen drawing exercises, and in-depth explanations of drawing techniques — all the information you need to start creating your own beautiful botanical illustrations today.

For as little as $57, you’ll get access to 5 lessons, in-depth tutorials, instructional videos, example sketches, supply recommendations, and more.

Learn how to cultivate a practice of drawing as well as the skills to slow down, focus, and see plants in our new Botanical Drawing for Herbalists course!