All About Wild Cherry Bark (Printable Monograph)

Wild cherry bark has been used in a variety of ways in years past to support the health of the body. Today, we want to peel back the layers so you can learn all about wild cherry bark and how to use it in your home or your herbal practice.

Not only are we going to share this information with you, but we’ve got a free printable monograph for you so you can have this information on hand whenever you find yourself in need of it!

How Getting To Know One Herb At A Time Can Make You A Better Herbalist

In addition to enrolling in an herbal school, it can be beneficial to become familiar with herbs by studying them one at a time.

Just like people, when we spend time with one plant at a time, we are able to forge a more intimate connection. We often encourage our students to start exploring herbs as simples—drinking a tea of just one herb, or tasting a single plant tincture—for just this reason. Tea blends and herbal compounds are wonderful in their own right, but sometimes less is more. By simplifying the interaction, we can focus on the plant that is right in front of us and tune in to it more easily.

This goes for study time, too—most herbalists swoon at a stack of good herbal books, but even just one book can be an overwhelming amount of information to take in! By focusing our study lens on one plant, we are able to retain more meaningful information as we scour multiple resources.

We encourage you to take the time to dive in deeply and really get to know the characteristics of one plant at a time—and not just what you learn in books, but how you observe a plant in nature and how you experience a plant by spending time with it or taking it into your body. By doing so, you will slowly build your understanding of each plant, and over time will amass a body of deep knowledge of the plants you have chosen to include in your materia medica. We feel that it is more helpful and meaningful to get to know a handful of plants really well than dozens of plants superficially.

The Herbarium membership is a great addition or alternative to enrolling in an online program.

We include hundreds of plant monographs in our courses and The Herbarium for good reason! Not only are the plants at the heart of our study of herbalism, they are also our connection to both the ancient and modern systems of healing that herbalism embodies and to the green world that has supported us for millennia. We believe in our hearts that the plants are worthy of study and celebration and encourage all of our students to do so. It is for this reason that we are offering this course to guide our readers and students to study the plants, one by one, and begin creating your materia medica.

Two Resources To Help You Learn More About Individual Herbs

With the launch of our newest course, Herbal Materia Medica Course, we’d like to share how a membership to The Herbarium complements this course perfectly by giving you a sneak peek at one of the herbal monographs included in your Herbarium membership—wild cherry bark.

Getting To Know Wild Cherry Bark

The information below is an exact replica of the wild cherry bark monograph you’ll find in The Herbarium. We also have a free printable of this monograph that you can download and print to add to your herbal materia medica at the end of this post.

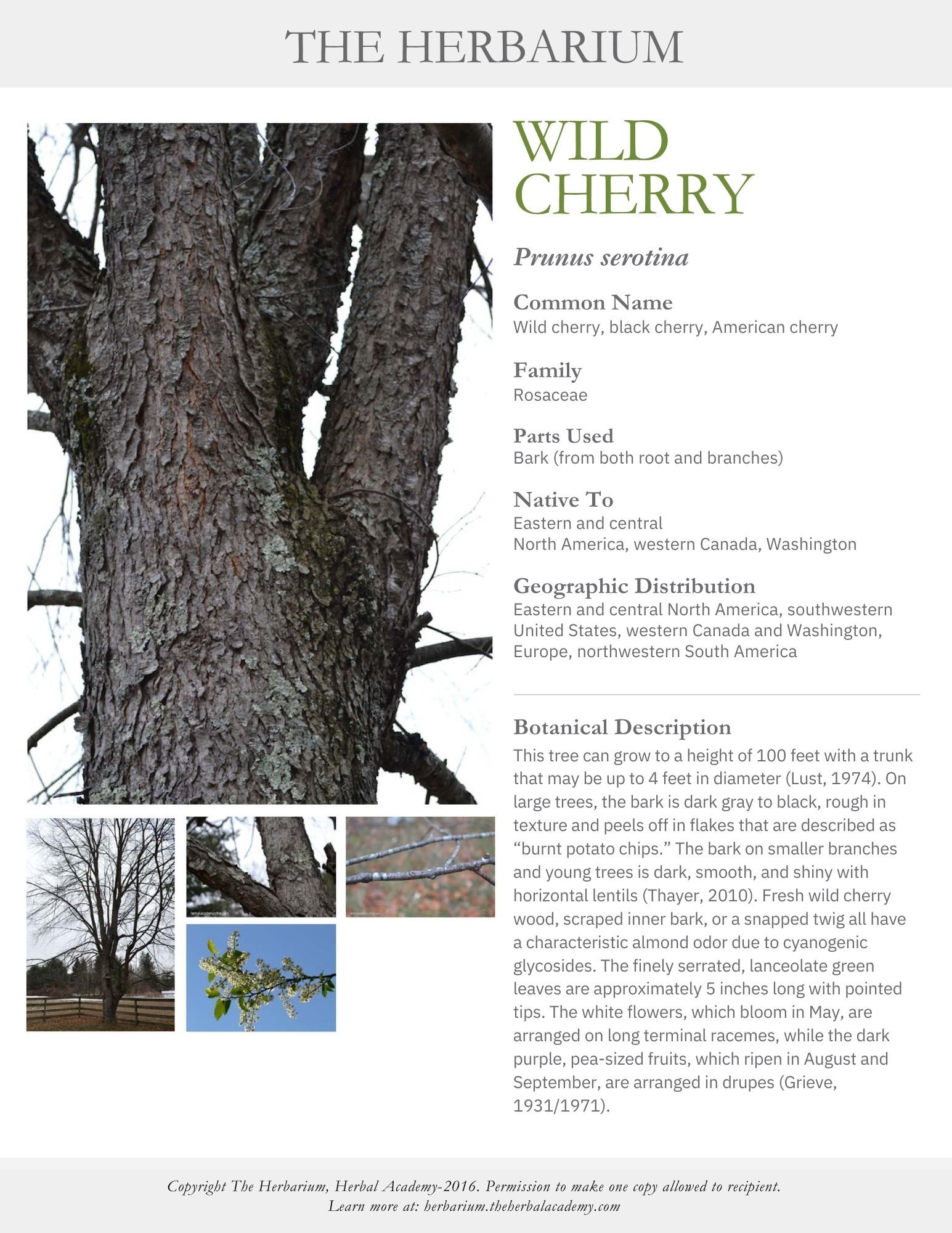

Wild Cherry (Prunus serotina)

Wild Cherry (Prunus serotina)

Common Name

Wild cherry, black cherry, American cherry

Family

Rosaceae

TCM Name

N/A

Ayurvedic Name

N/A

Parts Use

Bark (from both root and branches)

Native To

Eastern and central North America, western Canada, Washington

Geographic Distribution

Eastern and central North America, southwestern United States, western Canada and Washington, Europe, northwestern South America

Botanical Description

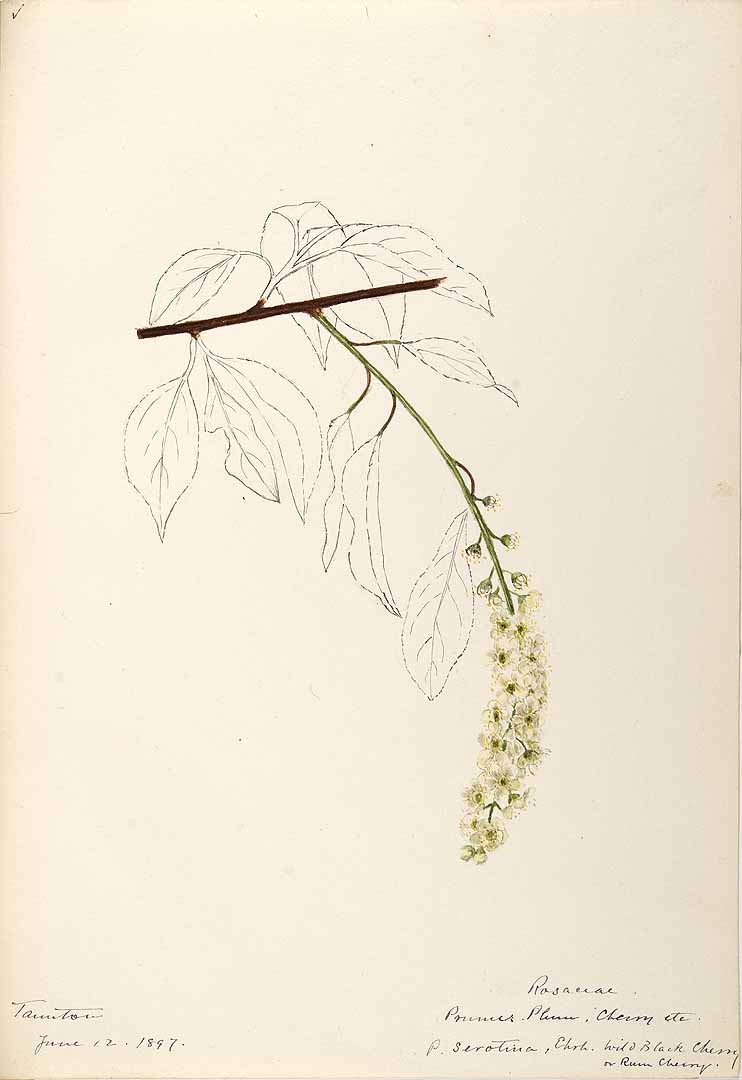

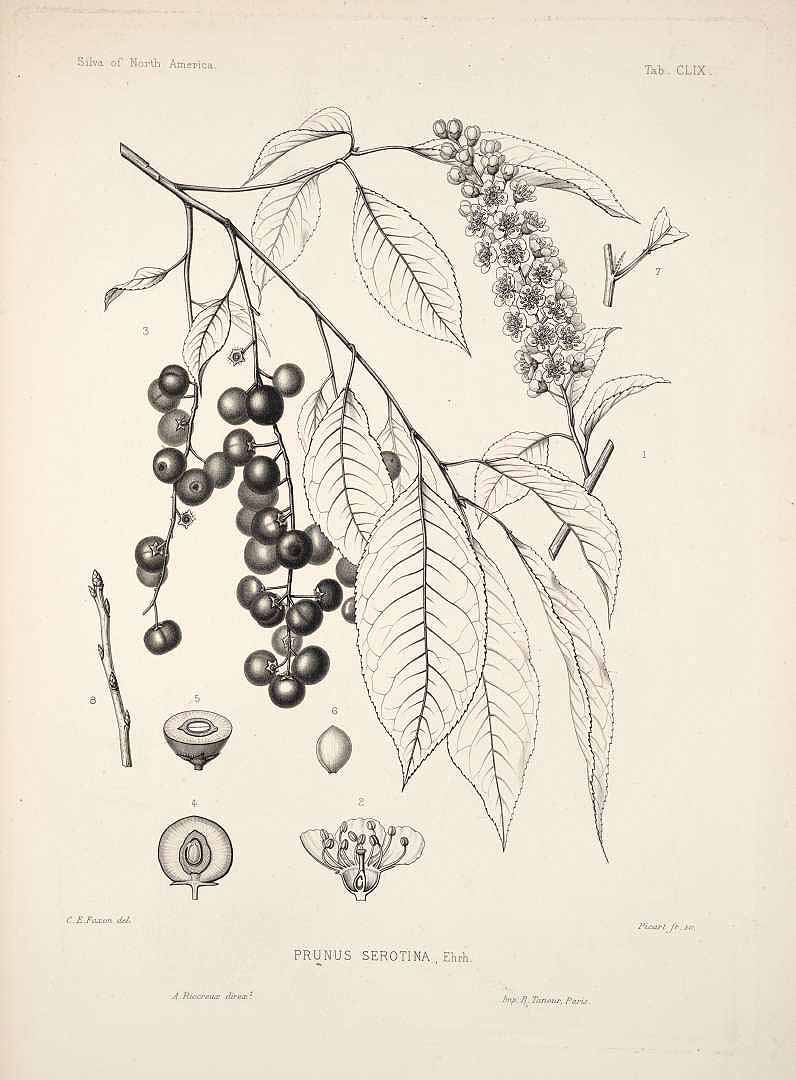

This tree can grow to a height of 100 feet with a trunk that may be up to 4 feet in diameter (Lust, 1974). On large trees, the bark is dark gray to black, rough in texture and peels off in flakes that are described as “burnt potato chips.” The bark on smaller branches and young trees is dark, smooth, and shiny with horizontal lentils (Thayer, 2010). Fresh wild cherry wood, scraped inner bark, or a snapped twig all have a characteristic almond odor due to cyanogenic glycosides. The finely serrated, lanceolate green leaves are approximately 5 inches long with pointed tips. The white flowers, which bloom in May, are arranged on long terminal racemes, while the dark purple, pea-sized fruits, which ripen in August and September, are arranged in drupes (Grieve, 1931/1971).

Key Constituents

Cyanogenic glycosides (prunasin and amygdalin), flavonoids, benzaldehyde, volatile oils, plant acids, tannins, calcium, potassium, and iron (Hoffmann, 2003; Holmes, 1997; Piorier, 2013).

Sustainability Issues

Wild cherry is considered invasive in Europe (Aerts et al., 2017). However, the plant is currently being reviewed for inclusion on the United Plant Savers “At-Risk” list (United Plant Savers, 2022), so careful and sustainable harvesting methods are especially important when harvesting from this tree in its native range.

Harvesting Guidelines

The inner bark of the branches and roots is harvested in the midsummer or fall (when the cyanogenic compounds are lower) and dried immediately for later use in teas and syrup or tincture extractions. One can harvest branches of smaller trees and use a knife or vegetable peeler to peel off the thin outer and inner bark, as opposed to harming the tree by taking the bark off its trunk. The fermented and/or wilted leaves and bark of wild cherry are toxic due to the conversion of cyanogenic glycosides into hydrocyanic acid—never harvest these from the ground. The leaves have higher levels of cyanogenic glycosides, so it is often recommended to avoid their use altogether; the bark has lower levels of these compounds and can be safely used in herbalism in normal doses, especially when dried (Ganora, 2021). However, the bark should be fully dried before use to minimize the amount of hydrocyanic acid; partially dried bark contains more hydrocyanic acid than either fully dried or even fresh bark (Gardner & McGuffin, 2013). See the safety section for more information.

Uses

Wild cherry is a large tree in the Rosaceae (rose) family. It is native to eastern and central North America and has expanded its range to the southwestern United States. It grows in hardwood forests and fields and along roadsides and fencerows, preferring rich, well-drained sandy loam (Thayer, 2010). It should be noted that chokecherry (Prunus virginiana) is sometimes confused with wild cherry, and while they are both members of the rose family and have some similar herbal actions, they are not the same tree. This monograph focuses on wild cherry (Prunus serotina).

Energetically, wild cherry is both cooling and warming as well as drying, with a sweet, bitter, and pungent taste. As a member of the rose family, wild cherry is an ally for the heart and sacral chakras, as it is sweet, loving, nurturing, and sensual. It helps open the heart, making space to lovingly communicate with and receive from others.

Wild cherry is indicated for an excited tissue state, meaning heat, redness, inflammation, and tenderness (Wood, 2008). Wild cherry is considered a general restorative in the case of chronic illness such as bronchitis or during convalescence from illness. Herbalist Peter Holmes (1997) explains that wild cherry can improve recovery time due to its ability to strengthen the heart, enkindle the appetite, clear excess heat, and restore vital energy.

Wild cherry has expectorant, antitussive, astringent, antispasmodic, anti-inflammatory, bitter, and nervine actions. Several Native American tribes have traditionally used wild cherry for a variety of ailments.

Mohegan tribe member Gladys Tantaquidgeon shares in her book that the Delaware people use the bark in a spring tonic as well as for diarrhea, even calling it “excrement tree,” and utilize the fruit in a cough syrup; while the Mohegan people of Connecticut combine the bark with boneset for colds, and ferment the berries for use with dysentery (Tantaquidgeon, 2001).

In Cherokee tradition, te ta ya or wild cherry bark is a valued part of many herbal blends as a tonic and a blood cleanser, according to Cherokee herbalist J.T. Garrett (2003). Wild cherry is used by the Cherokee people for its impact on the female reproductive system and usefulness in easing menstrual issues and even discomfort during childbirth (Garrett, 2003). The inner bark also has a reputation for supporting the bladder and urinary tract. Among its many uses in Cherokee culture, wild cherry bark is heralded as a relaxing sedative and astringent for both the nervous system, where it quells anxious nerves, and the digestive system, where it allays diarrhea (Garrett, 2003). But it is perhaps most valued in the respiratory system, where it astringes mucous membranes, eases coughs and spasms, and soothes bronchitis; the volatile oil is said to be used for asthma; in Cherokee tradition, wild cherry might be combined with wild plum (Prunus americana) to produce a cough syrup (Hamel & Chiltoskey, 1975; Garrett, 2003). In the upper respiratory system, too, wild cherry is indicated for sore throats and the common cold (Garrett & Garrett, 1996; Hamel & Chiltoskey, 1975). Topically, it is considered useful for sores on the skin (Garrett & Garrett, 1996); while the root bark makes a wash for ulcers and old sores (Hamel & Chiltoskey, 1975).

A male elder of the Potawatomi people shared that among the tribe, wild cherry bark is sometimes used as a strong purgative before entering into a ceremony (Toupal et al., 2006). Yet it is also used in formulas to cover up the flavor of disagreeable tasting preparations (Toupal et al., 2006).

Indeed, wild cherry’s most popular use is for coughs and for opening the lower respiratory system. Its sedative action is helpful for easing the cough reflex and calming irritating coughs (Hoffmann, 2003). It is a great herb for respiratory infections when there is a lot of mucus, coughing, and constricted airways that make breathing difficult. Due to its astringent, sedative, antispasmodic, and bronchodilator actions, wild cherry bark dries mucus, increases expectoration, eases coughing, and opens the airways. Also, wild cherry has a soothing effect on the respiratory tract due to its action as an expectorant (Wood, 2008). It is especially helpful for coughs that make it difficult to sleep through the night, and is nice in a cough syrup for this purpose. Wild cherry bark is used for bronchitis, whooping cough, and croup. It is also helpful for soothing unproductive, irritating coughs that linger after an infection is over (Piorier, 2013). Its cooling energy and anti-inflammatory action is helpful for inflammatory conditions such as acute and chronic sinus inflammation and allergies. As a bronchodilator, it also helps ease asthma and may be used with other herbs for this purpose (Hoffmann, 2003).

Not surprising for a member of the rose family, wild cherry is also a nourishing, tonifying, and strengthening herb for the heart, with the ability to calm cardiac irregularities and palpitations. Herbalist Matthew Wood (2008) likens wild cherry to hawthorn in that they are both part of the Rosaceae family and supportive for heart and digestive imbalances. Wild cherry’s nervine, sedative actions help slow circulation and heart rate, regulating palpitations and arrhythmia. By repairing irritation in the capillaries, the anti-inflammatory flavonoids in wild cherry ease circulatory congestion, as well as heat, redness, tenderness, and rapid heartbeat. The plant’s flavonoids also exert a noticeable cooling effect, along with cyanogens, which reduce cellular heat (Wood, 2008). This temperature regulation action can also be helpful in the case of fever. Wild cherry has a dual nature in that it can also be warming for those with cold skin and poor circulation to the extremities (Wood, 2008).

Wild cherry is also helpful for digestive upset thanks to its antispasmodic action, ability to soothe irritated mucosal tissues, and its digestion-stimulating bitter taste. Herbalist Matthew Wood (2008) emphasizes its action on the small intestine, explaining that the bark can function as a sedative for calming food sensitivities, and at the same time encourages adequate digestive secretions by way of its bitter properties. Wood (2008) indicates wild cherry for digestive conditions related to nervous irritation of the stomach and intestines, indigestion, and diarrhea. Its sedative, anti-inflammatory, and astringent actions are helpful with these conditions as well, calming the digestive tract, reducing inflammation and irritation, and reducing water volume in stool.

The cooling and anti-inflammatory actions of wild cherry also make it useful as an external wash for sores, ulcers, herpes, and shingles.

Scientific studies indicate wild cherry bark exhibits antiproliferative activity in human colorectal, pancreatic, prostate, and breast cancer cells by modulating nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug activated gene-1 (Yamaguchi et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2014). Another scientific study shows that wild cherry exhibits antibacterial action, inhibiting growth of Neisseria gonorrhoeae solates (Cybulska et al., 2011).

Wild cherry bark tea and syrup are often prepared as a cold infusion of dried bark and water, although some herbalists decoct or make a tincture of the bark. It’s worth researching the options and experimenting to determine which preparation method is most effective for you.

Ways to Use

Cold infusion, Decoction, Tincture, Syrup

Actions

Expectorant, Antitussive, Astringent, Antispasmodic, Anti-inflammatory, Cardiotonic, Bitter, Nervine, Sedative

Taste

Bitter, Slightly sweet, Pungent

Energy

Cooling, Drying

Adult Dose

- Tincture: 1-2 mL (1:5, 40%) 3x/day (Hoffmann, 2003).

- Infusion: 1.5-6 g dried bark/day divided into 1-3 doses (Mills & Bone, 2005).

Safety

Wild cherry contains prunasin and amygdalin, which are compounds known as cyanogenic glycosides (mcdonald, n.d.). David Hoffmann (2003) states “theoretically, large doses of wild cherry bark are toxic” (p. 576), presumably due to the cyanogenic glycosides, which are metabolized into hydrocyanic acid (cyanide). Cyanogenic glycosides are also present in many rose family plants, including apple seeds, peach pits, and hawthorn seeds (Piorier, 2013). Livestock animals have been poisoned by ingesting large amounts of the wilted wild cherry leaves (Ganora, 2021) and/or seeds, and there have also been reports of fatalities among children who have chewed the twigs, consumed the seeds, or drunk a tea made from the leaves of this plant (Mills & Bone, 2005). However, the body is able to detoxify low levels of hydrocyanic acid, and thus dried wild cherry bark can be used safely, even in children (Ganora, 2021; Piorier, 2013). That said, it’s important to note that the fermented and/or wilted leaves and bark of wild cherry are toxic due to the conversion of cyanogenic glycosides into hydrocyanic acid (Ganora, 2021), so never harvest these from the ground. The leaves have higher levels of cyanogenic glycosides, so it is often recommended to avoid their use altogether; the bark has lower levels of these compounds and can be safely used in herbalism in normal doses, especially when dried (Ganora, 2021). However, the bark should be fully dried before use to minimize the amount of hydrocyanic acid; partially dried bark contains more hydrocyanic acid than either fully dried or even fresh bark (Gardner & McGuffin, 2013).

References

- Aerts, R., Ewald, M., Nicolas, M., Piat, J., Skowronek, S., Lenoir, J., … & Honnay, O. (2017). Invasion by the alien tree Prunus serotina alters ecosystem functions in a temperate deciduous forest. Frontiers in Plant Science, 8, 179. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00179

- Cybulska, P., Thakur, S.D., Foster, B.C., Scott, I.M., Leduc, R.I., Arnason, J.T., & Dillon, J.R. (2011). Extracts of Canadian First Nations medicinal plants, used as natural products, inhibit neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with different antibiotic resistance profiles. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 38(7), 667-671. https://doi.org/10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31820cb166

- Ganora, L. (2021). Herbal constituents: Foundations of phytochemistry (2nd ed). HerbalChem Press.

- Gardner, Z., & McGuffin, M. (2013). American Herbal Products Association’s botanical safety handbook (2nd ed.). CRC Press.

- Garrett, J.T. (2003). The Cherokee herbal: Native plant medicine from the four directions. Inner Traditions.

- Garrett, J.T., & Garrett, M.T. (1996). Medicine of the Cherokee: The way of right relationship. Simon and Schuster.

- Grieve, M. (1971). A modern herbal. Dover Publications. (Original work published 1931). Retrieved from http://botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/c/chewil56.html

- Hamel, P.B., & Chiltoskey, M.U. (1975). Cherokee plants and their uses: A 400 year history. Herald Publishing.

- Hoffmann, D. (2003). Medical herbalism. Healing Arts Press.

- Holmes, P. (1997). The energetics of Western herbs (4th ed., Vol. 2). Snow Lotus Press.

- Lust, J. (1974). The herb book. Bantam Books.

- mcdonald, J. (n.d.). Wild cherry. https://www.herbrally.com/monographs/wild-cherry

- Mills, S., & Bone, K. (2005). The essential guide to herbal safety. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Piorier, E. (2014). Plant profile: Wild cherry bark. Retrieved from https://minnesotaherbalist.wordpress.com/2014/07/29/plant-profile-wild-cherry-bark/

- Tantaquidgeon, G. (2001). Folk medicine of the Delaware and related Algonkian Indians. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

- Thayer, S. (2010). Nature’s garden: A guide to identifying, harvesting, and preparing edible wild plants. Forager’s Harvest Press.

- Toupal, R.S., Banks, O.C., & Carroll, K.J. (2006). An ethnobotany of Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore: A baseline study emphasizing plant relationships of the Miami and Potawatomi peoples final report (vol. 1). University of Arizona. https://www.csu.edu/cerc/researchreports/documents/AnEthnobotanyIndianaDunesNationalLakeshoreVolume1.pdf

- United Plant Savers. (2022). Species at-risk list. https://unitedplantsavers.org/species-at-risk-list/

- Wood, M. (2008). The earthwise herbal: A complete guide to new world medicinal plants. North Atlantic Books.

- Yamaguchi, K., Liggett, J.L., Kim, N.C., & Baek, S.J. (2006). Anti-proliferative effect of horehound leaf and wild cherry bark extracts on human colorectal cancer cells. Oncology Reports, 15(1), 275-281. https://doi.org/10.3892/or.15.1.275Yang, M.H., Kim, J., Khan, I.A., Walker, L.A., & Khan, S.I. (2014). Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug activated gene-1 (NAG-1) modulators from natural products as anti-cancer agents. Life Sciences, 100(2), 75-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2014.01.075

Scientific Research

- Anti-proliferative effect of horehound leaf and wild cherry bark extracts on human colorectal cancer cells.

- Comparison of kinetic and molecular properties of two forms of amygdalin hydrolase from black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.) seeds.

- Development of the potential for cyanogenesis in maturing black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.) fruits.

- Evaluation of the hydroxynitrile lyase activity in cell cultures of capulin (Prunus serotina).

- Extracts of Canadian First Nations medicinal plants, used as natural products, inhibit neisseria gonorrhoeae isolates with different antibiotic resistance profiles.

- Flavonoids from Prunus serotina Ehrh.

- High-performance liquid chromatographic identification of flavonoid monoglycosides from Prunus serotina Ehrh.

- Identification of monomeric and polymeric 5,7,3’4′-tetrahydroxyflavan-3,4-diol from tannin extract of wild cherry bark USP, Prunus serotina Erhart, family Rosaceae.

- Immunocytochemical localization of mandelonitrile lyase in mature black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.) seeds.

- Immunocytochemical localization of prunasin hydrolase and mandelonitrile lyase in stems and leaves of Prunus serotina.

- Investigation of the microheterogeneity and aglycone specificity-conferring residues of black cherry prunasin hydrolases.

- Isolation and characterization of multiple forms of mandelonitrile lyase from mature black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.) seeds.

- Isolation and characterization of multiple forms of prunasin hydrolase from black cherry (Prunus serotina Ehrh.) seeds.

- Localization and catabolism of cyanogenic glycosides.

- Multiple introductions boosted genetic diversity in the invasive range of black cherry (Prunus serotina; Rosaceae).

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug activated gene-1 (NAG-1) modulators from natural products as anti-cancer agents.

- Nutraceutical value of black cherry Prunus serotina Ehrh. fruits: Antioxidant and antihypertensive properties.

- The occurrence and seasonal distribution of C50-C60-polyprenols and of C100-and similar long-chain polyprenols in leaves of plants.

- Prunus serotina amygdalin hydrolase and prunasin hydrolase: Purification, n-terminal sequencing, and antibody production.

- Prunus spp. intoxication in ruminants: A case in a goat and diagnosis by identification of leaf fragments in rumen contents.

- Quantitative analysis of amygdalin and prunasin in Prunus serotina Ehrh. using (1) H-NMR spectroscopy.

- A simple and highly sensitive spectrophotometric method for the determination of cyanide in equine blood.

- Simultaneous quantification by HPLC of the phenolic compounds for the crude drug of Prunus serotina subsp. capuli.

- Temporal and spatial expression of amygdalin hydrolase and (R)-(+)-mandelonitrile lyase in black cherry seeds.

- Tissue and subcellular localization of enzymes catabolizing (R)-amygdalin in mature Prunus serotina seeds.

- Tissue level compartmentation of (R)-amygdalin and amygdalin hydrolase prevents large-scale cyanogenesis in undamaged Prunus seeds.

- [Toxic and less toxic plants. 39. Prunus padus, Prunus serotina].

- Vasoactive and antioxidant activities of plants used in Mexican traditional medicine for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases.

Where to Buy

Free Wild Cherry Bark Monograph Printable

Now that you’ve learned about wild cherry bark, we’d like to offer you a free download and print of our wild cherry bark monograph. Simply click the link, save the monograph PDF to your computer, print it off, and add it to your herbal materia medica for future reference.

Now that you’ve learned about wild cherry bark, we’d like to offer you a free download and print of our wild cherry bark monograph. Simply click the link, save the monograph PDF to your computer, print it off, and add it to your herbal materia medica for future reference.

Download the Wild Cherry Bark Monograph as a PDF

Don’t forget to check out our Herbal Materia Media Course which is free during the month of January 2017, and if you haven’t already, check out The Herbarium and how it can make creating an herbal materia medica even easier for you!