Introductory Herbal Course Lesson Preview

This preview lesson has been taken from the Online Introductory Herbal Course. The Introductory Herbal Course is made up of 6 Units and over 34 Lessons, dozens of charts and visuals, videos, and herbal monographs. To learn more about the Introductory Herbal Course, please visit the course registration page. We’d love to have you join our Herbal Academy family!

Learn More

UNIT 2, LESSON 2: KITCHEN MATERIA MEDICA

INTRODUCTION

In this section, we will explore the use of kitchen herbs used by herbalists for specific indications including digestion, infection, and inflammation. Keep in mind that herbs typically have multiple actions, which often overlap in helpful ways. Ginger (Zingiber officinale), for example, can fall into all three of these categories: it is used as a digestive aid, to help fight infections, and as an anti-inflammatory.

Often, the line between food and herb is blurred: food can be used in herbalism, and herbs can be used as food. What we know for sure is that the food and herbs we choose to prepare can be a source of important phytochemicals to help us live long and vital lives!

KITCHEN HERBS USED FOR DIGESTION

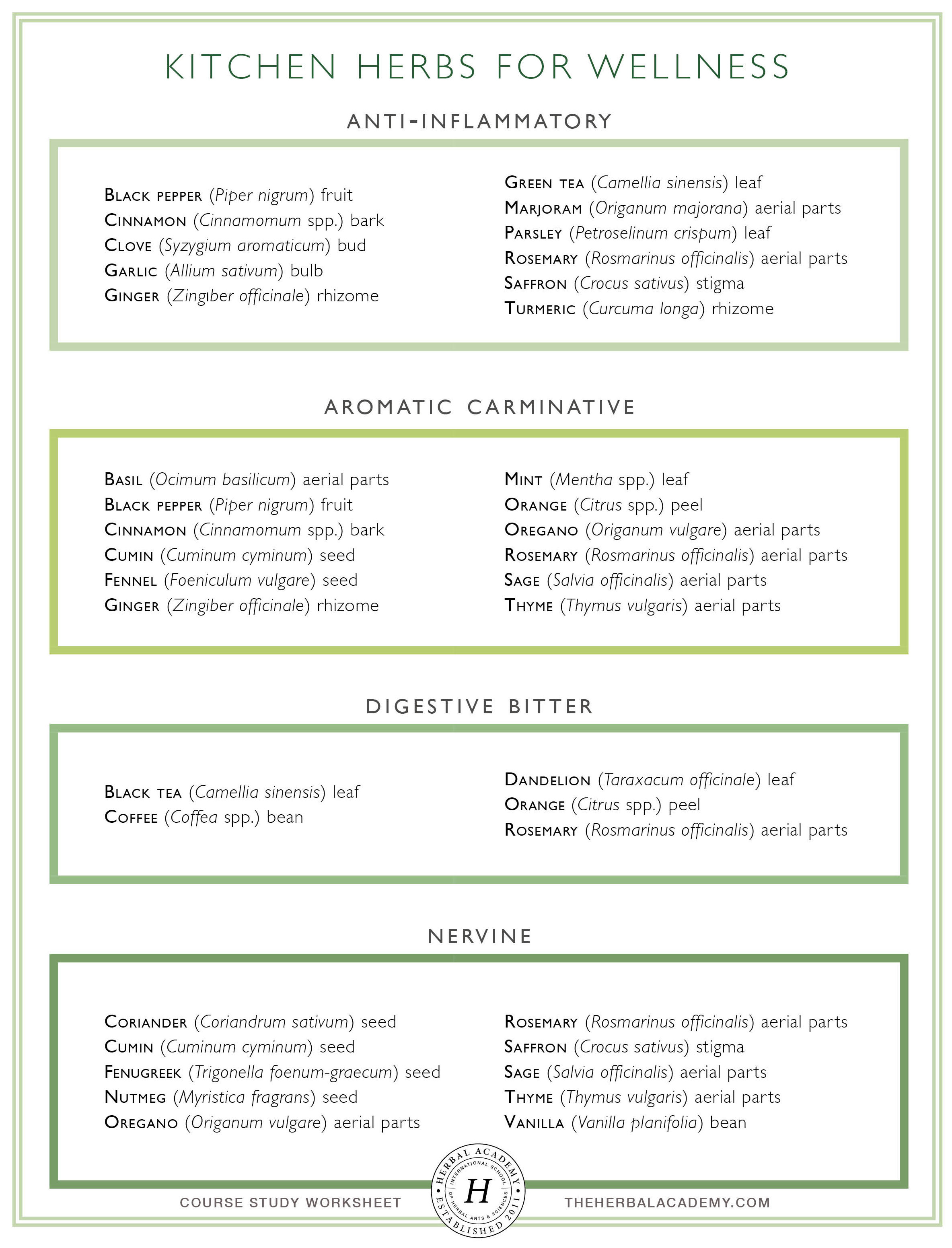

Cultures around the world have long combined certain herbs and spices with hard-to-digest foods and this practice is still used, sometimes unconsciously, by most people today. Herbs and spices that aid digestion typically fall into two categories: aromatics and bitters.

Aromatics

Aromatics, as the name implies, are highly fragrant herbs with a high volatile oil content. Volatile oils relax smooth muscles and ease our nervous system into rest-and-digest mode, which helps improve our ability to digest and assimilate food. Common aromatic kitchen herbs include basil (Ocimum basilicum), thyme (Thymus vulgaris), oregano (Origanum vulgare), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), ginger (Zingiber officinale), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.), black pepper (Piper nigrum), sage (Salvia officinalis), and mint (Mentha spp.). Aromatics are often paired with heavy, fatty foods like cheese, oils, and animal protein, to help lighten them up and improve their digestibility.

Bitters

Bitter herbs help us digest and assimilate nutrients by increasing digestive secretions throughout the gastrointestinal tract. The very taste of bitter on the tongue triggers salivation, with a subsequent chain reaction all the way down to the intestines. In particular, the bitter flavor stimulates bile flow from the liver and gallbladder, which plays a key role in digesting fats. Ever wonder why salads are traditionally eaten at the beginning of a meal? A nice bitter salad of fresh spring dandelion greens prepares the digestive system for the meal ahead! Common kitchen bitters include rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), orange peel (Citrus spp.), chicory (Cichorium intybus), endive, radicchio, dandelion greens, some lettuces, coffee, and tea.

Dandy Chamomile Bitters

Bitters are used to stimulate digestion through the action of the bitter taste, which stimulates digestive secretions. When taken before a meal, herbal bitters ready the digestive system and stimulate appetite. To experience the effect of an herbal bitter, wait 15 minutes or so after taking it and you may find that you start to feel hungry and ready to eat!

2 tbsp dandelion (Taraxacum officinale) root

2 tbsp chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) flower

2 tbsp orange (Citrus spp.) peel

1 tbsp fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) seed

1 cup vodka or brandy

- Follow instructions for making a tincture in Unit 1.

- Take 3-5 drops directly on the tongue before meals to stimulate digestion.

Join Guido Masé, RH (AHG) for a video tutorial on crafting an herbal bitters blend!

Download the making bitters video transcript as a PDF

Common Kitchen Herbs That Aid Digestion

Fennel – Foeniculum vulgare (Apiaceae) – Seed

Fennel is an easy annual to grow in the garden. Start it early so it has plenty of time to mature its seeds! Wild fennel isn’t quite as graceful as its garden cousin—less uniform, and bearing an unkempt appearance reflecting its wildness, it typically grows in disturbed areas along roadsides and in abandoned lots. In places that enjoy a Mediterranean climate, wild fennel grows so prolifically that it’s often considered an invasive weed. To harvest fennel seeds, look for mature flower heads on a warm afternoon. Wild seeds will be smaller, darker, and more irregular than seeds from cultivated varieties of fennel. Clip off the flower head and pinch off seeds while still green.

Actions: Antiemetic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antispasmodic, aperient, carminative, diuretic, galactagogue

Energetics: Warming and drying

Use: Have you ever noticed the bowl of fennel seeds at the door of many Indian restaurants? Sweet, slightly bitter, and pungent fennel seeds are readily available and make a perfect pre- or post-meal nibble to ward off digestive symptoms and support digestion. Fennel seed tea is another traditional way to support digestion in both Mediterranean and Indian traditions.

Fennel is an aromatic herb and a valuable carminative. Fennel helps to ease nausea, moves gas down and out of the digestive system, stimulates appetite and digestion, and is useful for colic and constipation—try making fennel seeds into a delicious cordial!

Fennel’s antiemetic, antispasmodic, and carminative actions are attributed primarily to its volatile oils, which are also responsible for its strong licorice-like aroma. The aromatic volatile oils relax the gastrointestinal tract to reduce muscular pain and symptoms caused from tension in the gut (Bone & Mills, 2013).

Safety: Hypersensitivity can occur from consuming fennel, especially in individuals who are sensitive to other plants in the Apiaceae (parsley) family (Mills & Bone, 2005).

Dose: Infusion/Decoction: 1-2 g dried seed/day divided into 1-3 doses (Mills & Bone, 2005); Tincture: 1-2 mL (1:5, 40%) 3x/day (Hoffmann, 2003).

Rosemary – Rosmarinus officinalis (Lamiaceae) – Aerial parts

Ah, Rosmarinus, the beautiful “dew of the sea,” a fragrant, oceanside, Mediterranean evergreen mint with aromatic pine needle-like branches. Associated with the Virgin Mary, rosemary’s affinity with the feminine is also illustrated by the medieval belief that rosemary growing in door yards signified that a woman ruled the roost in that household (Grieve, 1931)!

Actions: Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antispasmodic, astringent, bitter, carminative, cholagogue, circulatory stimulant, diaphoretic, emmenagogue, nervine

Energetics: Warming, drying, and stimulating

Use: Rosemary is an uplifting digestive tonic that helps to relax and tone the stomach and is especially good for digestive upset resulting from mental tension, anxiety, and worry due to its nervine action. As a cholagogue, rosemary stimulates the production of bile and its flow from the liver, thus stimulating digestion and aiding in detoxification (Hoffmann, 2003).

The volatile oils in rosemary are antimicrobial and diaphoretic, making rosemary an important ally for colds, sore throats, the flu, and coughs. It can also help clear congestion when infection does take hold, and rosemary has a long history of use “to dispel the foul air of disease and death” in homes, hospitals, and streets (McIntyre, 1996).

A friend not only to the digestive system, but also the nervous and circulatory systems, rosemary has long been used to increase circulation to the brain, improving focus and memory. In this way, it can also be helpful for headaches caused by nervous tension (Hoffmann, 2003).

Try adding rosemary to a cup of tea, craft a rosemary vinegar for salad dressings and marinades, or add it to soup, stew, and roasted vegetable recipes. Rosemary can be grown indoors in a pot year round.

Safety: Use only culinary amounts during pregnancy.

Dose: Infusion: 6-12 g dried herb/day divided into 1-3 doses (Mills & Bone, 2005); Tincture: 1-2 mL (1:5 in 40%) 3x/day (Hoffmann, 2003).

Cumin – Cuminum cyminum (Apiaceae) – Seed

Native to Egypt, cumin is a warm- and dry-weather loving annual plant used for its seeds, which are gathered in late summer. Cumin is commonly used in ayurvedic medicine and its Sanskrit name, jira, translates to “promoting digestion.”

Actions: Alterative, antibacterial, anticatarrhal, antiemetic, anti-inflammatory, antispasmodic, carminative, diuretic, emmenagogue, expectorant, galactagogue

Energetics: Warming to cooling, drying

Use: Like so many kitchen herbs, cumin is an ally for the digestive system, and is particularly helpful for lack of appetite, flatulence, bloating, slow transit time, and other signs of sluggish digestion. It can also be helpful for nausea and diarrhea. In India, roasted cumin seeds are often eaten after meals to ease the digestive process (Pole, 2012).

A popular ayurvedic tea formula for improving digestion and assisting the body in the excretion of metabolic waste contains cumin seed, coriander (Coriandrum sativum) seed, and fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) seed and is commonly referred to as CCF tea (Lad, 2009).

In addition to its digestive uses, cumin can be used as an anticatarrhal and expectorant when there is excess mucus in the chest or sinuses. It is also traditionally used for the constriction associated with asthma. For these purposes, cumin works best as a tea. In the same way, it can also be useful for excess vaginal discharge and irritation (McIntyre & Boudin, 2012).

Safety: Allergic reactions to cumin are known to occur. Large doses of cumin should be avoided by individuals with kidney disease (Gardner & McGuffin, 2013).

Dose: Infusion/decoction: 0.5-5 g dried seed/day divided into 1-4 doses; Tincture: 1-5 mL (1:3, 45%) 3x/day (Pole, 2012).

Orange – Citrus spp. (Rutaceae) – Peel

Orange peel is an easy herb to add to your home apothecary and as a fragrant addition to potpourri. Just save the peels from the organically grown oranges you buy at the grocery store. To prepare dried orange peel, shave off the white pith on the underside of the peel, lay them in a basket or even a plate to dry, and store in an airtight jar in a cool, dark place. If you live in a humid environment, the peels can be placed in a 150 degrees F oven for 45-60 minutes to complete the drying process. They can also be purchased dried in bulk.

Actions: Antimicrobial, bitter, carminative, choleretic, orexigenic

Energetics: Warming and drying

Use: Orange peel is a great addition to a carminative tea or tincture formula. Mildly bitter, orange peel strengthens digestive function and is useful for gas, nausea, diarrhea, and bloating and to stimulate the appetite (McBride, 2010). Orange peel is perfect for moist, stagnant digestion, as it removes phlegm from both the digestive and respiratory tracts.

Orange peel is high in vitamin C and has been used to enhance immune function in general as well as during colds and the flu (Grosso et al., 2013). It has substantial volatile oil content (evident if you’ve ever been squirted in the eye while peeling an orange!), which has antibacterial properties. Alcohol extract of orange peel has demonstrated activity against cavity-causing oral bacteria (Shetty et al., 2016)—consider adding it to an herbal mouthwash blend!

Safety: In human studies, the fruit juice of bitter orange (C. x aurantium) has been shown to interact with the drug metabolizing enzyme CYP3A4, so caution is advised when using orange peel with prescription drugs that are metabolized by CYP3A4 (Gardner & McGuffin, 2013).

Dose: Infusion: 0.25-0.5 g dried peel/day divided into 1-3 doses; Tincture: 0.5-1 mL (1:5, 70%) 3x/day (Alexander & Straub-Bruce, 2014).

After Dinner Tea

Kitchen spices are combined with garden herbs in this after dinner tea that encourages digestion.

2 tsp chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla) flower

1 tsp bee balm (Monarda spp.) aerial parts

1 tsp orange (Citrus spp.) peel

1 tsp fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) seed, anise (Pimpinella anisum) seed, or cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum) seed

2 cups water

- Follow instructions for making an herbal infusion in Unit 1.

KITCHEN HERBS USED FOR RESPIRATORY INFECTION

Garlic (Allium sativum) and many other kitchen herbs with high volatile oil content are highly antimicrobial, while helping to bring blood (and warmth) from the core of the body to the periphery, thereby helping to “break” a fever and shorten the duration of an infection. Other antimicrobial kitchen herbs include cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.), thyme (Thymus vulgaris), oregano (Origanum vulgare), horseradish (Armoracia rusticana), fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum), black pepper (Piper nigrum), ginger (Zingiber officinale), sage (Salvia officinalis), cumin (Cuminum cyminum), and cayenne (Capsicum annuum).

Antimicrobial kitchen herbs can be taken as tea or added to soup. After a little experimentation, you may find that you prefer some in a soup stock rather than a tea, such as garlic, ginger, horseradish, and cayenne, but any of these aromatic herbs can be used to enhance your favorite broth, whether it is chicken, miso, bone, mushroom, or vegetable based. Generally, it is recommended to add these herbs at the end of cooking to preserve their delicate volatile oils.

Herbs should not be relied on for serious infections as a substitute for immediate medical attention. Serious infections, such as sepsis, can progress rapidly to multiple organ failure and fatality if untreated.

Common Antimicrobial Kitchen Herbs

Garlic – Allium sativum (Amaryllidaceae) – Bulb

Used for at least 5,000 years as a food and an herb, an ancient Chinese proverb states of this member of the Allium (onion) genus: “Garlic is as good as ten mothers” (Ryther, 2013). Known as “the stinking rose,” garlic’s strong odor and pungency were believed to ward off evil spirits, werewolves, vampires, and hungry tigers, and the bulbs were even used as currency in ancient Egypt (Rupp, 2014). These days, its qualities are undisputed.

Actions: Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, cholagogue, diaphoretic, diuretic, expectorant, hypolipidemic, hypotensive

Energetics: Warming

Use: An immune system stimulant, diaphoretic, expectorant, and antimicrobial, the raw cloves of garlic are used to support the body’s response to respiratory conditions in the winter months. Garlic can ease some of the discomforts of a cold through its anti-inflammatory action, as well as shorten its duration by stimulating the immune system, thinning mucus, and breaking a fever.

Garlic cloves can be used on athlete’s foot and other skin infections (try garlic infused honey for these purposes!) and in oil infusion ear drops with mullein (Verbascum thapsus) flower for ear infection.

To retain garlic’s beneficial properties it should not be heated at a high temperature or for too long. Spread on toast or add to tea towards the end of steeping time and add plenty of sweetener and lemon! To avoid stomach irritation, take garlic with honey, olive oil, or food.

Safety: Those with gastrointestinal sensitivities or ulcers may find that garlic aggravates their condition. Use only culinary amounts if on blood thinners and during pregnancy, in the postpartum period, and during lactation. Avoid 2 weeks before and after surgical procedures (Mills & Bone, 2005).

Dose: A clove of garlic can be eaten daily for general support or 1 clove of garlic can be taken 3x/day during acute infections (Hoffmann, 2003).

Oregano – Origanum vulgare (Lamiaceae) – Aerial parts

Though oregano is a vigorous grower in Europe and throughout the Mediterranean, worldwide demand for the herb has threatened wild populations. Thankfully, oregano can be grown in the home garden or in a pot and spreads readily once established. Harvest oregano leaves and stem tips, just as the plant begins to flower. Avoid harvesting oregano during cold, wet spells, since the volatile oil content diminishes under these conditions. Cut stems about five inches from the ground, bundle, and hang them to dry in a warm, shaded place.

Actions: Anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antioxidant, carminative, diaphoretic, expectorant, emmenagogue, nervine

Energetics: Warming and drying

Use: Though oregano is perhaps most often associated with pizza, it has surprising therapeutic applications. Oregano contains important vitamins and minerals including iron, calcium, magnesium, potassium, omega-3 fatty acids, and vitamins A, C, K, and E (United States Department of Agriculture, 2015).

Historically, oregano was often associated with good luck and happiness. In Greek and Roman wedding ceremonies, brides and grooms often wore crowns fashioned from oregano branches and oregano growing on a loved-one’s grave signified a happy afterlife for the deceased (Grieve, 1931).

In herbalism, oregano’s first documented use dates back 50,000 years to Iraq where archeologists discovered the grave of an apparent noble woman who had a small bag of oregano tied around her neck. Researchers have also found oregano-infused olive oil in an ancient Grecian ship in the Aegean Sea and theorize that it was most likely used as a therapeutic rub and as a food preservative (Bagchi et al., 2016).

Today, oregano is used for its expectorant, diaphoretic, and antimicrobial properties, which make it very helpful for respiratory conditions, such as colds and the flu. Oregano also makes a relaxing after-dinner carminative tea, perhaps tempered with some peppermint, chamomile, or lemon balm for those who feel that the taste is too pungent.

Oregano can be added to a respiratory sinus steam and used as an anti-inflammatory leaf poultice, infused in oil, or made into tea or tincture. Of course, it can be used with abandon in cooking, as well!

Safety: Allergic sensitivity to oregano has been reported (Gardner & McGuffin, 2013).

Dose: Infusion: 6-8 g dried aerial parts/day, divided into 2-3 doses. Tincture: 1-3 mL (1:3; 45%) 3x/day (Holmes, 1989).

Ginger – Zingiber officinale (Zingiberaceae) – Rhizome

Tongue-tingling and pungent, this tropical rhizome’s culinary and herbal uses are detailed extensively in early Chinese and Indian medical texts as well as ancient Roman, Greek, and Arabic traditions.

Actions: Anodyne, antiemetic, anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, antispasmodic, carminative, choleretic, circulatory stimulant, diaphoretic, expectorant, orexigenic

Energetics: Warming and drying

Use: Ginger is well known for its use in nausea, but it is also a potent antimicrobial and has many helpful applications for colds and the flu. Ginger’s volatile oils stimulate the immune system to fight both bacterial and viral infections (McIntyre, 1996) and ginger is an all-around warming immune stimulant that is delicious and useful in cold and flu season beverages. Many herbalists use it at the first signs of viral infection and find that it can abort the onset of upper respiratory infections (Holmes, 1997). Ginger’s antiviral actions include stimulating macrophage activity, preventing viruses from attaching to cell walls, and acting as a virucide (Buhner, 2013).

Ginger also possesses other actions that make it useful as a catalyst in antimicrobial herbal formulas, helping to increase their action by dilating blood vessels and enhancing circulation.

Ginger is traditionally used fresh, as the antimicrobial action is most effective in the fresh rhizome. Herbalist Stephen Harrod Buhner (2013) states, “If you are using ginger as an antiviral, the fresh juice cannot be surpassed in its effectiveness” (p.168). Fresh ginger juice can also be applied topically to skin infections.

Safety: Avoid high doses when combined with anticoagulant medications (Mills & Bone, 2005).

Dose: Infusion: 1.5-3 g fresh herb/day divided into 1-4 doses (Mills & Bone, 2005); Tincture: 1.5-5 mL (1:5 in 40%), 3x/day (Hoffmann, 2003).

Fresh Ginger Juice Tea

Adapted from Herbal Antivirals by Stephen Harrod Buhner (Buhner, 2013).

¼ cup freshly squeezed ginger (Zingiber officinale) rhizome juice

1½ cups hot water

1 tbsp raw honey

Juice and rind of ¼ lime

⅛ tsp cayenne (Capsicum annuum) fruit powder

- Combine the ginger juice, water, honey, lime juice/rind, and cayenne in a drinking vessel.

- Drink 4-6 cups/day during acute illness.

Ginger-Cinnamon Tea

A delicious way to warm the body and keep infection at bay.

1-2 inch piece peeled and chopped ginger (Zingiber officinale) rhizome, fresh

2 cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.) sticks

Honey or maple syrup to taste (optional)

2 cups water

- Place ginger and cinnamon in a saucepan with water.

- Bring to boil then lower to a simmer and cover.

- Simmer for 20-30 minutes.

- Strain and serve. Sweeten with honey or maple syrup if desired.

Cinnamon Ginger Coconut Oil

Adapted from The Herbal Kitchen by Kami McBride (McBride, 2010).

1 cup coconut oil, melted

2 tbsp cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.) bark powder

1 tsp ginger (Zingiber officinale) rhizome powder

1 tsp anise (Pimpinella anisum) seed powder

- Place herbs into a sterilized, dry glass jar and pour the coconut oil over them. This oil will sit for 4 weeks before it’s ready, so be sure to choose a jar that won’t allow much air above the oil to avoid rancidity.

- Shake the jar occasionally; warm slightly and stir with a clean, dry spoon if it becomes solidified.

- Enjoy after 4 weeks—no straining necessary!

- This warming oil is delicious in oatmeal, baked goods, curries, and on toast with honey.

KITCHEN HERBS USED FOR INFLAMMATION

The term “inflammation” typically refers to an overactive or prolonged immune response. In the cardiovascular system, for example, inflammation occurs at the endothelial level (the inner lining of the blood vessels) and is linked to atherosclerosis. This inflammation, in addition to high cholesterol, can contribute to coronary artery disease. Other common inflammatory disorders include asthma, arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, pelvic inflammatory disease, and acne.

Diet and lifestyle can play a role in encouraging or down-regulating inflammatory processes in our bodies. Anti-inflammatory foods include whole, unprocessed plant-foods high in phytonutrients and antioxidants (most colorful fruits and vegetables are anti-inflammatory), as well as monounsaturated fats found in avocados and nuts. Foods linked to higher inflammation levels include refined carbohydrates (white bread, pastries, etc.), fried foods, sugar, soda, processed meat, and margarine (Harvard Medical School, 2017).

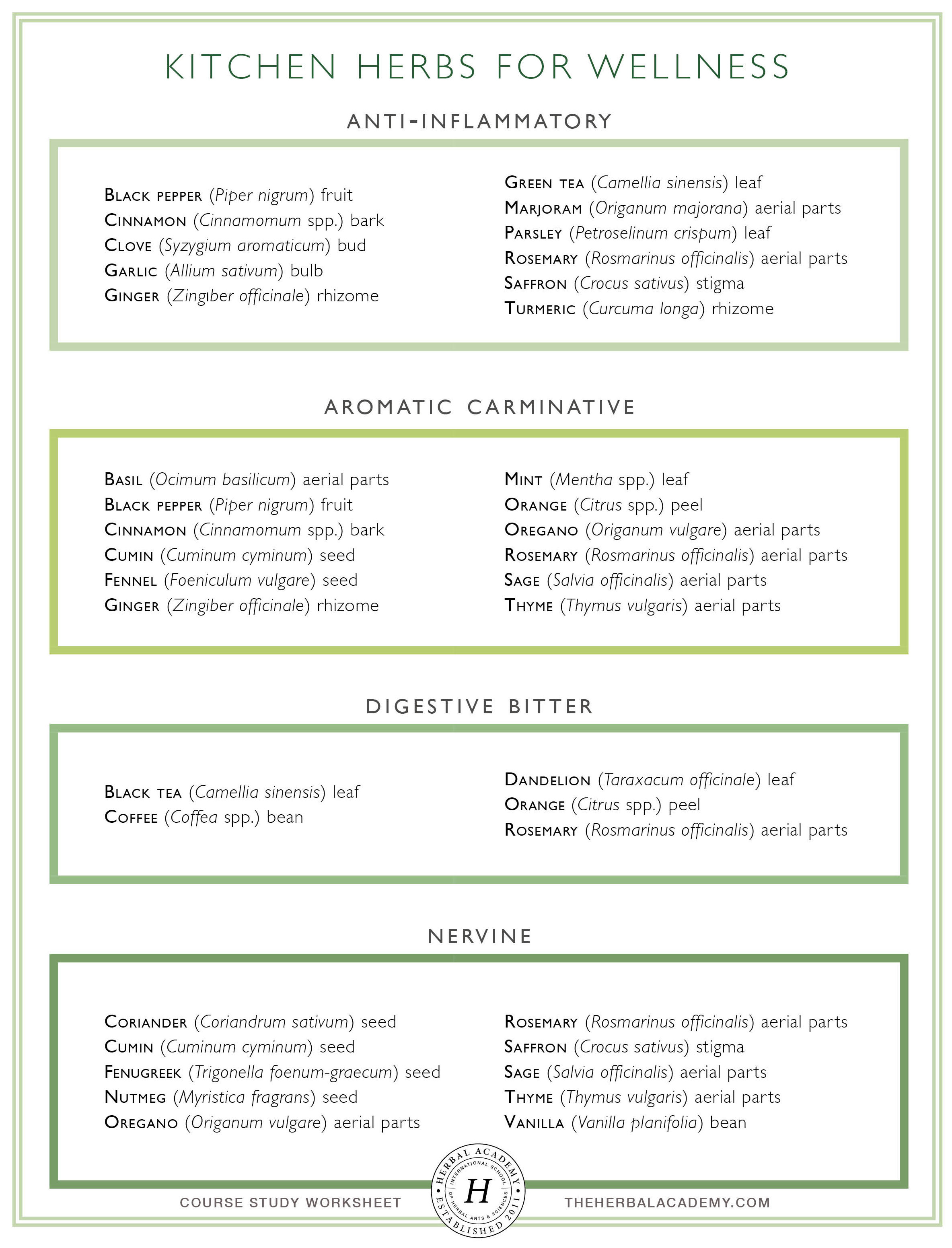

Many kitchen herbs are anti-inflammatory. These include garlic (Allium sativum), parsley (Petroselinum crispum), turmeric (Curcuma longa), cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.), black pepper (Piper nigrum), ginger (Zingiber officinale), green tea (Camellia sinensis), marjoram (Origanum majorana), clove (Syzygium aromaticum), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), and saffron (Crocus sativus).

Anti-Inflammatory Kitchen Herbs

Turmeric – Curcuma longa (Zingiberaceae) – Rhizome

Like its cousin ginger (Zingiber officinale), the part of turmeric used is the rhizome—a horizontal stem that grows underground. Turmeric root gets its vibrant yellow color from a group of polyphenolic compounds called curcuminoids. Collectively, these curcuminoids are sometimes called “curcumin.” Curcuminoids have received a substantial amount of research attention, and are sometimes considered to be the primary anti-inflammatory compound in turmeric. However, other compounds have also been shown to have bioactivity and clinical relevance (Bone & Mills, 2013) and the argument for synergy of the numerous compounds in whole-plant extract may eventually have both science and tradition on its side.

Actions: Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, carminative, cholagogue, hepatic, hypolipidemic, hypoglycemic

Energetics: Warming

Use: Turmeric is best known as a musculoskeletal anti-inflammatory; however, its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and immune-regulating effects extend throughout the body and turmeric is also used for managing inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, particularly in inflammatory bowel diseases and gastric ulcers.

Turmeric and its constituents have been demonstrated clinically to inhibit inflammatory pathways, decrease oxidative damage in the body, and lower low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol levels (Bengmark et al., 2009; Qin et al., 2017; Vera-Ramirez et al., 2013).

The human body does not assimilate the curcumin in turmeric well unless it is consumed with something that enhances its bioavailability, such as black pepper. The piperine in black pepper enhances the bioavailability of the curcumin in turmeric by up to 2000% (Dudhatra et al., 2012).

Safety: Large doses of turmeric (greater than 15 g/day) should not be taken long term by those with congestive heart failure (Mills & Bone, 2005). Individuals with bile duct obstruction should avoid the use of turmeric. Because turmeric has slight anti-platelet activity, stop using turmeric 2 weeks before surgery (Gardner & McGuffin, 2013).

Dose: Infusion/Decoction: 3-9 g dried rhizome/day divided into 1-3 doses; Powder: 1-4 g/day; Tincture: 1-4 mL (1:1, 50%) 3x/day (Bone & Mills, 2013).

Green tea – Camellia sinensis (Theaceae) – Leaf

The tea plant is an evergreen bush that naturally grows in warm, humid climates with significant rainfall. Native to China and India, most tea is now grown commercially throughout Asia, though small-scale artisanal tea farms have cropped up in the United States, Europe, and Australia. Green, white, oolong, and black tea are all derived from the same plant species, but they differ in their fermentation and aging processes, which in turn affects the concentration of some beneficial phytonutrients.

Actions: Anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, astringent, hypolipidemic, vascular tonic

Energetics: Cooling, drying, and stimulating

Use: Of all the Camellia sinensis preparations, green tea typically contains the highest amount of the anti-inflammatory and antioxidant flavonoids for which it is famous. Green tea boosts the process of detoxification that occurs in the liver, thus helps the liver do its job of keeping the level of inflammatory compounds in the body at a manageable level (Romm, n.d.).

Green tea has a number of beneficial effects on the vascular endothelium that play a role in warding off inflammation, atherosclerosis, and the formation of blood clots (Babu et al., 2008). Green tea also has a positive effect on blood lipid levels by reducing low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels, increasing high-density lipoprotein (HDL) levels, and preventing oxidation of LDL (Cooper et al., 2005).

One Japanese study of green tea drinkers followed over 40,000 adults for up to 11 years. Compared to those drinking less than 1 cup of green tea per day, the individuals consuming 5 cups a day or more showed lower risk of death from all causes, and specifically from cardiovascular disease, with women receiving notably stronger protection than men (Kuriyama et al., 2006).

Safety: Green tea contains varying amounts of caffeine; water-processed decaffeinated tea may be a better choice for those sensitive to the effects of caffeine. Green tea can be very astringent, especially if prepared with a long infusion time, and may not be appropriate for some individuals with sensitive or irritated gastrointestinal conditions or an overly dry constitution. Combining with demulcent herbs can offset this effect.

Dose: There is no clear consensus on therapeutic dosing, and the level of catechins and other polyphenols can vary widely in tea. In some observational studies, more does appear to be better, with additional health benefits conferred by drinking 10 cups as compared to 3 cups, or more than 3 cups compared to less than 1 cup (Cooper et al., 2005). However, many studies use an average of 3-5 cups/day; this is equivalent to about 300 milligrams of tea extract, or 3 grams of dry leaf (Babu et al., 2008). This may be taken as an encapsulated herb, or may be powdered and used in smoothies or other food preparations.

KITCHEN HERBS USED FOR THE NERVOUS SYSTEM

Herbs that tonify the nerves and support nervous system function are known as nervines. Some nervines are relaxing, while others are more stimulating, and plenty of nervine herbs can be found on the kitchen spice rack! (Note: The nervous system will be discussed in more depth in Unit 4.)

Kitchen herbs with nervine properties include coriander (Coriandrum sativum), cumin (Cuminum cyminum), fenugreek (Trigonella foenum-graecum), nutmeg (Myristica fragrans), oregano (Origanum vulgare), rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), sage (Salvia officinalis), saffron (Crocus sativus), thyme (Thymus vulgaris), and vanilla (Vanilla planifolia).

Coriander – Coriandrum sativum (Apiaceae) – Seed

Coriander is the seed of the same aromatic plant that produces cilantro leaf, another popular culinary herb. Coriander is easily cultivated as a garden herb or potted plant. During its earlier stages of growth, coriander requires a cool environment to prevent bolting, but prefers warm weather once established. The green leaves are harvested before the plant goes to flower, and the fruits are harvested when ripe, as they will fall to the ground once dry.

Actions: Alterative, analgesic, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antispasmodic, carminative, diaphoretic, diuretic, emmenagogue, galactagogue, hepatic, hypolipidemic, nervine

Energetics: Cooling

Use: The seeds of the coriander plant have carminative and nervine actions, helping to ease digestion and relax the nerves and are particularly useful when nervous conditions lead to digestive imbalance or vice versa.

In Iran, coriander has a tradition of use for insomnia, depression, anxiety, and epilepsy (Laribi et al., 2015; Sahib et al., 2013) and it is also a commonly employed herb in ayurvedic medicine. According to Ayurveda, coriander is unique in that unlike many aromatic spices, it has a cooling energy. Its cooling nature makes it useful for pitta type emotions (e.g., anger and irritability) and imbalances (e.g., acid reflux, intestinal spasm, and inflammatory gut disorders) (Frawley & Lad, 2001).

For culinary purposes, coriander leaves (cilantro) are best used fresh. They may also be frozen or tinctured for later use. Ground coriander seed is lovely sprinkled in soups, and in general has the ability to harmonize with a wide range of flavors from spicy hot and savory to sweet. It can also be taken as an infusion or tincture.

Safety: Allergic reactions to coriander are known to occur. Individuals on blood sugar medication should only take high doses of coriander when under the care of a qualified healthcare professional (Gardner & McGuffin, 2013).

Dose: Infusion/decoction: 1-30 g dried seed/day divided into 1-4 doses; Tincture: 1-5 mL (1:3, 45%) 3x/day (Pole, 2012).

Nutmeg – Myristica fragrans (Myristicaceae) – Seed

Native to Indonesia, nutmeg comes from a large tree that is now cultivated in many tropical regions. Both nutmeg and mace, another common kitchen spice, come from the same tree—mace is a bright red webbing, known as an aril, that surrounds the nutmeg seed. Nutmeg has a sweet, spicy flavor most frequently associated with holiday pies and eggnog. In herbalism, nutmeg is a low-dose herb the can benefit the nervous, digestive, and respiratory systems.

Actions: Analgesic, aphrodisiac, astringent, carminative, emmenagogue, expectorant, nervine, sedative

Energetics: Warming

Use: Nutmeg is a relaxing nervine indicated for pain, insomnia, low libido, and mental irritation. A cup of warm milk (dairy or non-dairy) with an ⅛ teaspoon of nutmeg is a soothing evening preparation for easing the body into sleep and quieting the mind (Pole, 2012).

Nutmeg’s astringent nature eases diarrhea and excess mucus in the lungs. Its pungent taste can help to spark appetite and calm indigestion and flatulence. Topically, powdered nutmeg can be made into a paste and applied as an analgesic to the head or joints for headaches or joint pain (McIntyre & Boudin, 2012).

In Ayurveda, nutmeg is used to enkindle the digestive fire and is mixed with buttermilk for childhood diarrhea (Pole, 2012). Though it is widely regarded in Ayurveda as a superior aphrodisiac and nervous system tonic for an agitated mind that has difficulty concentrating, it is only used for short periods of time because of its heavy nature, which can “dull” the mind (Frawley & Lad, 2001).

Safety: While culinary use is fine during pregnancy, higher than culinary amounts of nutmeg should not be taken during pregnancy. A dose of 5 g/day has been demonstrated to cause “nutmeg poisoning,” which includes symptoms such as facial flushing, tachycardia, hypertension, nausea and vomiting, blurred vision, and hallucinations. Fatalities have been reported (Gardner & McGuffin, 2013).

Dose: Decoction: 0.5-1 g unroasted seed/day, divided into 1-3 doses (Gardner & McGuffin, 2013).

Basil – Ocimum basilicum (Lamiaceae) – Aerial parts

A member of the Lamiaceae (mint) family, basil is most well known for its strong aroma and distinct flavor. It is commonly paired fresh with tomatoes in the culinary world, or used in its dried form in a variety of dishes. Easy to grow as an annual in most gardens, basil does well in a sunny, warm spot. Leaves (and flowers, if desired) can be harvested throughout the growing season.

Actions: Alterative, analgesic, anticatarrhal, antiemetic, antimicrobial, antioxidant, antispasmodic, carminative, diaphoretic, galactagogue, nervine

Energetics: Warming and drying

Use: As with most kitchen herbs, however, its uses are not limited to adding distinct flavors to food. Basil is high in antioxidants, which protect cells from the damage caused by free radicals in the body (Vlase et al., 2014), as well as vitamins A, C, and K, and folate (United States Department of Agriculture, 2015).

In herbalism, basil is used as an uplifting nervine for stress, anxiety, low mood, and poor memory and concentration (McIntyre & Boudin, 2012). As do many nervines, basil positively impacts the digestive system, where it helps to improve digestion and the absorption of nutrients (no wonder it makes such a great culinary herb!), as well as ease indigestion, nausea, and intestinal spasm (Tierra, 1998).

Basil is also used for respiratory conditions and is specifically indicated for excess mucus in the head and chest (McIntyre & Boudin, 2012). It can be an excellent addition to a tea blend for colds, the flu, and other respiratory infections.

Safety: While culinary use is fine during pregnancy, high doses of basil should not be taken during pregnancy (Gardner & McGuffin, 2013).

Dose: Infusion: 2-4 g dried aerial parts/day divided into 1-3 doses; Tincture: 2-4 mL (1:5, 75%) 3x/day (McIntyre & Boudin, 2012).

Download the Kitchen Herbs for Wellness Worksheet as a PDF

Experiential Exercise: Try New Flavors

It’s easy to fall into a rut when it comes to cooking, including the way that we incorporate herbs and spices into our meals. Some of us rely on the flavors that are familiar and that best complement our tried-and-true recipes. Or we may have limited experience with cooking in general, and rely solely on the basics of salt and pepper to season our plates.

By stepping out of our cooking comfort zones and expanding our palates, we may find something new that we love! At the same time, switching up our everyday spices by trying new flavor profiles can also be supportive to our health and wellness, because it introduces additional phytochemicals and nutrients to the body.

Begin this experiment by identifying two or three recipes that you’ve never tried and that have a different flavor profile than you are used to tasting. You might find recipes online or in a cookbook already on your shelf that you haven’t gotten around to looking at just yet.

A helpful tip: Traditional cuisines around the world tend to offer much in the way of herbs and spices, regardless of geography. If your experience of Italian food is limited to spaghetti and meatballs, try a bean soup recipe from the region. If you are already accustomed to the tastes of Italian food, you might try a Schezuan Chinese or an East African recipe. For those who already love the curries and dals of India, consider French dishes that incorporate the herbes de Provence. If you can tolerate spicy meals, but never cook them, you might try a Caribbean jerk recipe rich with allspice and peppers.

As you choose the recipes, take note of the herbs and spices included in them. Are they already familiar, or entirely new to you? You may also want to take some time to learn more about the herbs themselves—have you already come across them in your study of herbalism? If not, what can you find out about how these herbs may be used for supporting wellness?

CONCLUSION

Isn’t it exciting to discover that the kitchen spices that you’ve been using to flavor your soups and stews all along can also be used in herbalism? We think so! In this lesson and the last, we have given you a jumping off point for the gratifying exploration of the many ways that your kitchen spice jars can be put to use. In the next lesson, we’ll introduce you to a few fun ways to incorporate these spices into herbal preparations!

RECOMMENDED RESOURCES

Alchemy of Herbs by Rosalee de la Forêt

Healing Spices by Bharat B. Aggarwal and Debora Yost

Recipes from the Herbalist’s Kitchen by Brittany Wood Nickerson

The Herbal Kitchen by Kami McBride

REFERENCES

Alexander, L.M., & Straub-Bruce, L.A. (2014). Dental herbalism: Natural therapies for the mouth. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Babu, A., Pon, V., & Liu, D. (2008). Green tea catechins and cardiovascular health: An update. Current Medicinal Chemistry, 15(18), 1840-1850.

Bagchi, D., Preuss, H.G., & Swaroop, A. (2016). Nutraceuticals and functional foods in human health and disease prevention. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Bengmark, S., Mesa, M.D., & Gil, A. (2009). Plant-derived health: The effects of turmeric and curcuminoids. Nutricion Hospitalaria, 24(3), 273-281.

Bone, K., & Mills, S. (2013). Principles and practice of phytotherapy. St. Louis, MO: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier.

Buhner, S.H. (2013). Herbal antivirals. North Adams, MA: Storey Publishing.

Cooper, R., Morré, D.J., & Morré, D.M. (2005). Medicinal benefits of green tea: Part I. Review of noncancer health benefits. Journal of Alternative & Complementary Medicine, 11(3), 521-528. http://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2005.11.521

Dudhatra, G.B., Modey, S.K., Awale, M.M., Patel, H.B., Modi, C.M., Kumar, A., … Chauhan, B.N. (2012). A comprehensive review on pharmacotherapeutics of herbal bioenhancers. The Scientific World Journal, 2012, 637953. http://doi.org/10.1100/2012/637953

Frawley, D., & Lad, V. (2001). The yoga of herbs. Twin Lakes, WI: Lotus Press.

Gardner, Z., & McGuffin, M. (2013). American Herbal Products Association’s botanical safety handbook. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Grieve, M. (1931). A modern herbal. Retrieved from https://botanical.com/botanical/mgmh/mgmh.html

Grosso, G., Galvano, F., Mistretta, A., Marventano, S., Nolfo, F., Calabrese, G., … Scuderi, A. (2013). Red orange: Experimental models and epidemiological evidence of its benefits on human health. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity, 2013, 11 pages. http://doi.org/10.1155/2013/157240

Harvard Medical School. (2017). Foods that fight inflammation. Retrieved from https://www.health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/foods-that-fight-inflammation

Hoffmann, D. (2003). Medical herbalism: The science and practice of herbal medicine. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press.

Holmes, P. (1989). The energetics of Western herbs (Vol. 2). Boulder, CO: Snow Lotus Press.

Holmes, P. (1997). The energetics of Western herbs: Treatment strategies integrating Western and Oriental herbal medicine. Boulder, CO: Snow Lotus Press.

Kuriyama, S., Shimazu, T., Ohmori, K., Kikuchi, N., Nakaya, N., Nishino, Y., … Tsuji, I. (2006). Green tea consumption and mortality due to cardiovascular disease, cancer, and all causes in Japan: The Ohsaki study. JAMA, 296(10), 1255-1265. http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.10.1255

Lad, V. (2009). Ayurveda: The science of self healing. Twin Lakes, WI: Lotus Press.

Laribi, B., Kouki, K., M’Hamdi, M., & Bettaieb, T. (2015). Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.) and its bioactive constituents. Fitoterapia, 103, 9-26. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.fitote.2015.03.012

McBride, K. (2010). The herbal kitchen. San Francisco, CA: Conari Press.

McIntyre, A. (1996). Flower power. New York, NY: Henry Holt and Company, Inc.

McIntyre, A., & Boudin, M. (2012). Dispensing with tradition: A practitioner’s guide to using Indian and Western herbs the Ayurvedic way. Great Rissington, UK: Artemis House.

Mills, S., & Bone, K. (2005). The essential guide to herbal safety. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

Pole, S. (2012). Ayurvedic medicine: The principles of traditional practice. Philadelphia, PA: Singing Dragon.

Qin, S., Huang, L., Gong, J., Shen, S., Huang, J., Ren, H., & Hu, H. (2017). Efficacy and safety of turmeric and curcumin in lowering blood lipid levels in patients with cardiovascular risk factors: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrition Journal, 16(1), 68. http://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-017-0293-y

Romm, A. (n.d.). The adrenal thyroid revolution supplement guide. Retrieved from https://avivaromm.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/aviva_supplement_tables.pdf

Rupp, R. (2014). How garlic may save the world. National Geographic. Retrieved from https://www.nationalgeographic.com/people-and-culture/food/the-plate/2014/04/24/how-garlic-may-save-the-world/

Ryther, M.B. (2013). Garlic solutions: A guide to choosing, using and growing nature’s superfood. M.B. Ryther.

Sahib, N.G., Anwar, F., Gilani, A.H., Hamid, A.A., Saari, N., & Alkharfy, K.M. (2013). Coriander (Coriandrum sativum L.): A potential source of high‐value components for functional foods and nutraceuticals – a review. Phytotherapy Research, 27(10), 1439-1456. http://doi.org/10.1002/ptr.4897

Shetty, S.B., Mahin-Syed-Ismail, P., Varghese, S., Thomas-George, B., Kandathil-Thajuraj, P., Baby, D., … Devang-Divakar, D. (2016). Antimicrobial effects of Citrus sinensis peel extracts against dental caries bacteria: An in vitro study. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Dentistry, 8(1), e71–e77. http://doi.org/10.4317/jced.52493

Tierra, M. (1998). Planetary herbology. Santa Fe, NM: Lotus Press.

United States Department of Agriculture. (2015). Nutrient database for standard reference. Retrieved from https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/

Vera-Ramirez, L., Perez-Lopez, P., Varela-Lopez, A., Ramirez-Tortosa, M., Battino, M., Quiles, J.L. (2013). Curcumin and liver disease. Biofactors, 39(1), 88-100. https://doi.org/10.1002/biof.1057

Vlase, L., Benedec, D., Hanganu, D., Damian, G., Csillag, I., Sevastre, B., … Tilea, I. (2014). Evaluation of antioxidant and antimicrobial activities and phenolic profile for Hyssopus officinalis, Ocimum basilicum and Teucrium chamaedrys. Molecules, 19(5), 5490-5507. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules19055490