The Virtues of Violets – Health Benefits of Violets

A few weeks ago, I looked around our 5 acres to see what may be sprouting after a long, cold winter. Soon I saw that my first little escaped and self-sown flowering plant had emerged. Guess which one. Violet! Perhaps cultivated for hardiness as well as beauty, the little johnny jump-up violets (Viola tricolor) had popped up after self-sowing the year before. They beat the dandelions! Now that’s pretty tough for a little violet. The many violets in eastern North America love to cross breed, making their identification difficult (Erichsen-Brown, 1979) with over 40-50 species depending on how you count. “Phew!” “That’s a relief,” I say. Why? When it comes to their medicinal properties, they are, for the most part, interchangeable. So, let’s pick just a few, and we’ll explore the health benefits of violets.

Getting to Know the Violets

The best known violets for medicinal purposes are the European varieties. The most popular is the sweet violet or Viola odorata. It is one of the violets native to Europe and it has been widely cultivated into many forms over the years (Gleason, and Cronquist, 1963). The petals are deep violet and vary to white. The flowers are quite fragrant. V. odorata is best known as a cough remedy especially for bronchitis (Hoffman, 2003).

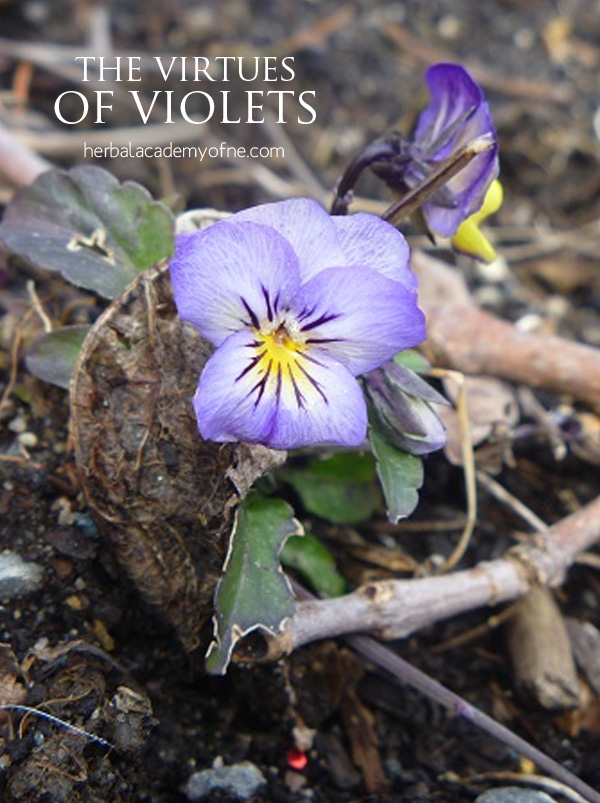

Sweet violet’s sister is Viola tricolor which is better known by her common name: pansy. She is also a native of the Old World and has been widely cultivated and still is. Like her relatives, V. tricolor has been used as an expectorant, diuretic, and anti-inflammatory. Used both internally and topically, this violet is helpful for cystitis, rheumatic complaints, eczema, psoriasis, acne, and topically for babies with cradle cap (Hoffman, 2003).

Viola tricolor

Just for the record, who are our native violets? One is Viola papilionacea, and, the other is V.sororia. Both are called the common blue violet. There is also the lesser known V. pedata, the birds foot violet, that should be mentioned. Why? This species was the native plant species widely collected, and provided through the Shaker herbal medicine catalogues published between 1830-1895 (Miller, 1998). Now, this violet is on the threatened species list for New Hampshire and endangered list for New York from its over-harvesting. (USDA Plants Database). It differs by having a bird’s claw shape to its leaves, instead of heart-shaped. If you find this species, don’t pick it! (Instead, please, tell me!)

The common blue violets have deep purple blooms and heart-shaped leaves. These are the little blue violets that we may find in our lawns, (if we allow the grass to grow), and also in meadows and damp woodlands. Both species mentioned above; Viola papilionacea and V. sororia, have the same characteristics as their more popular relatives, as a remedy for coughs, colds and sore throats. These we may wild-harvest, mindfully. (That is, if you find more than 10 plants, then you may harvest 3-4 plants.)

Common Blue Violet

More on Violet Lore and Science

The accounts of their uses abound for all the violets. As far back as 1885, a study compared violet leaf vitamin C content to that of oranges and vitamin A content to that of spinach. From the basal leaves, if collected in spring, this early research reported that violets contain twice as much vitamin C as the same weight of orange and more than twice the amount of vitamin A, gram for gram, when compared with spinach! (Erichsen-Brown, 1979).

Early European recipes made syrup of the blossoms and traditionally it was used as a laxative for infants and children (Grieve, 1996). Sweet violet, also, has a long history of use as a cough remedy, especially bronchitis, and functions as an expectorant, as well as an anti-inflammatory (Hoffman, 2003).

Many of the older European-based herbalists, such as Grieve, who first published A Modern Herbal in 1931, and De Bairacli Levy (1973), note that violet has been used, historically, for the treatment of cancer. In America, there are accounts of Native Americans utilizing violet for cancer treatment (Erichsen-Brown, 1979). To my surprise, the American National Cancer Institute has been made aware of the folk uses of violets for cancer since at least the 1950s. (Erichson-Brown, 1979).

Have we studied this herb for further evidence of violet’s potential effects on cancer? Yes! One recent study concluded that an aqueous Viola extract (i.e. tincture) inhibited the proliferation of activated lymphocytes (Hellinger, 2014) as well as negatively affecting other hyper-responsive immune functions. This indicates that violets may be useful in the therapy of disorders related to an overactive immune system (Hellinger, 2014). This little powerhouse-plant is right here, in our back yards!

Violet Blossoms Are to Eat. Violet Leaves Are to Drink.

On the lighter side, violet flowers have been long used as “sweat meats,” by dipping whole flowers in a mixture of melted cane sugar, lemon juice, and egg-white and then dropping them into cold water to “set hard” the sugar coating (Grieve, 1996).

Seasonally-minded local food restaurants that I have visited use violet blossoms to garnish a fresh spring greens salad or a fresh French Sorrel soup. Their petite deep purple blooms draw our attention to look at them mindfully.

Better still, Juliette writes that violet (blossoms and leaves) have been known to have a relaxing effect by “calming deranged nerves, improving weak memory and soothing restlessness” (De Bairacli Levy, 1973). See below for suggestions for herbal combinations for tea.

Violets are virtuous, vivacious, and valuable! Violets are unassuming but oh, so powerful! They herald our early spring blooms in the wild and garden. Their long history of medicinal use begs that we give them more crucial attention and recognition.

How to Use Violets

You can start with making tea! Fresh herbs or dried may be used. A little can go a long way. I usually use 1 teaspoon of dried herbs for a cup of tea or 1 tablespoon per pint or 16 ounces of water. The easiest but less elegant way to brew tea is to put your loose tea into a canning jar, add boiling water and allow it to steep to your desired strength, then strain the herbs. Usually 5-10 minutes of steeping is enough.

Violet Leaf Tea

1 tablespoon of loose tea steeped in 16 ounces of boiling water for about 10 minutes. Strained loose leaves from the jar.

Violet Leaf Tea

A Spring Tonic Tea with Violet

Try combining equal amounts of the dried leaves of dandelion, nettle, red clover, violet and mint (peppermint or spearmint). This is a highly nutritious tea.

A Calming Tea with Violet

Combine violet leaves with blue vervain, linden leaf and flower and elderflower. (Garland, 1979) This won’t be sedating but instead will give you an “ahhh” feeling.

Mineral Rich Tea with Violet

Combine violet leaves with alfalfa, horsetail, oatstraw, red clover, hawthorn leaf and flower, chamomile, and raspberry leaves (Soule, 1998). This tea is packed with vitamin C, vitamin A, iron, and calcium.

No side effects or drug interactions have been reported for violets. There are no reported risks for pregnancy or lactation that are noted (Brinker, 2010). Enjoy your violet tea!

Violets are best used as decorative garnishes when it comes to cooking as mentioned above. You may collect a few wild plant blossoms to decorate a salad or garnish a soup. Their blossoms are a beautiful bit of spring to find on your plate or in your bowl.

In the garden, you may want to plant a patch of perennial violets near your entry or add to a perennial border with other plants. Use pansies to circle a small tree in your yard. Or, keep your violets in pots on your sill or deck to admire. They’ll need some shade in the full heat of summer. Keep them watered, and you’ll be able to enjoy them for a good part of the season!

This post was written by Rachel Ross of Hillside Herbals. Rachel grew up between two nature sanctuaries and received a degree in biology and a Masters in Botany. Later, she acquired an RN, and MSN, and is now a practicing Certified Nurse-Midwife. She sees the plants as powerful allies to nourish, strengthen, calm, and heal. Her humble hope is to share this knowing with you.

Photos in this article are provided and copyrighted by Rachel Ross.

REFERENCES

Brinker, Francis. (2010) Herbal Contraindications and Drug Interactions plus Herbal Adjuncts with Medicines. Fourth Edition. Eclectic Medical Publications, Sandy, Oregon.

De Bairacli Levy, Juliette. (1973) Common Herbs for Natural Health. Schocken Books. New York.

Erichsen-Brown, Charlotte. (1979) Medicinal and Other Uses of North American Plants; a Historical Survey with Special Reference to the Eastern Indian Tribes. Dover Publications. New York.

Garland, Sarah. (1979) The Complete Book of Herbs and spices. Frances Lincoln Publishers Limited. London.

Gleason, Henry, A., and Cronquist, Arthur. (1963) Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada. D. Van Nostrand Company. New York.

Grieve, M. (1996) A Modern Herbal. Barnes and Noble Books. New York.

Hellinger, R., Koehbach, J., Fedchuck, H., Sauer, B., Huber, R., Gruber, CW., and Grundemann, C., ( 2014) Immunosuppressive activity of an aqueous Viola tricolor herbal extract. J. Ethnopharmacol. Jan 10;151(1):299-306.

Hoffman, David. (2003) Medical Herbalism; The Science and Practice of Herbal Medicine. Healing Arts Press. Rochester, Vermont.

Miller, Amy Bess. (1998) Shaker Medicinal Herbs; A compendium of history, lore, and uses. Storey Books. Schoolhouse Rd., Pownal, Vermont 05261.

http://plants.usda.gov/core/profile?symbol=VIPE