De Materia Medica: The Ancient Text that Changed the World

There is a grand mystery and pleasure in reading ancient texts that can still fulfill our curiosities about the human experience. Writings about herbalism are no exception, as they give us a sense of how our ancestors lived, survived, and interacted with the natural world around them. De Materia Medica, Latin for “On Medical Material” is a surviving text from the first century written by Pedanius Dioscorides (c. 40-90 CE), a Greek medical botanist and physician who served in the Roman army. His five-volume manuscript describes approximately 600 plants for more than 1,000 traditional medicines. Centuries after it was written, Dioscorides’ celebrated herbal reference would become the basis of European and Western pharmacopeia.

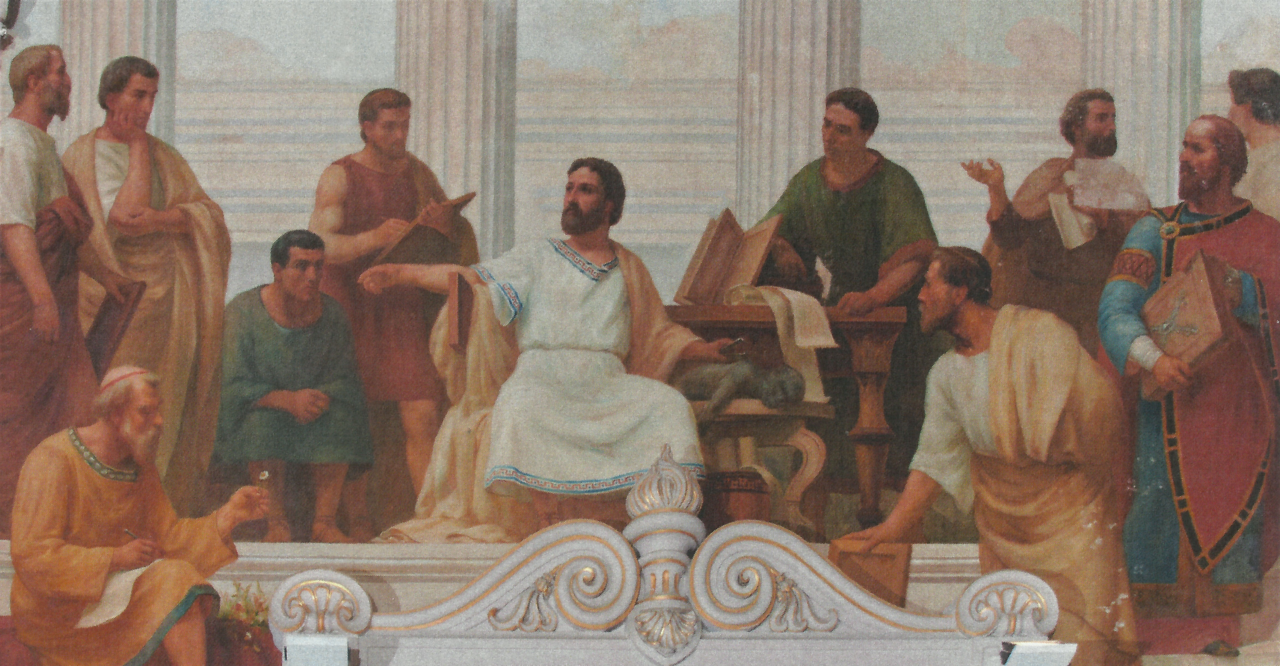

Dioscorides is seated in the bottom left of this painting. He is shown examining a flower while he takes notes. (“Medicine in the Middle Ages” (1906), by Veloso Salgado.) NOVA Medical School, Public Domain.

Spreading Herbal Knowledge

As an army surgeon, Dioscorides traveled throughout the ancient world and observed, collected, and applied hundreds of plants to his medical practice. Because of his detailed descriptions of plant remedies from many different regions, Dioscorides became a trusted source of knowledge applicable to many. His textbook, originally written in ancient Greek with the title Περὶ ὕλης ἰατρικῆς, was subsequently translated, most often by religious monks, into Latin, Arabic, Italian, German, Spanish, and French as it gained increasing popularity across the European and African continents. For the first time in known history, information about medicinal plants and remedies were more easily documented and distributed across diverse cultures and languages. His De Materia Medica, hand-copied and edited countless times, would be extensively referenced by physicians and herbalists for the following 1,500 years.

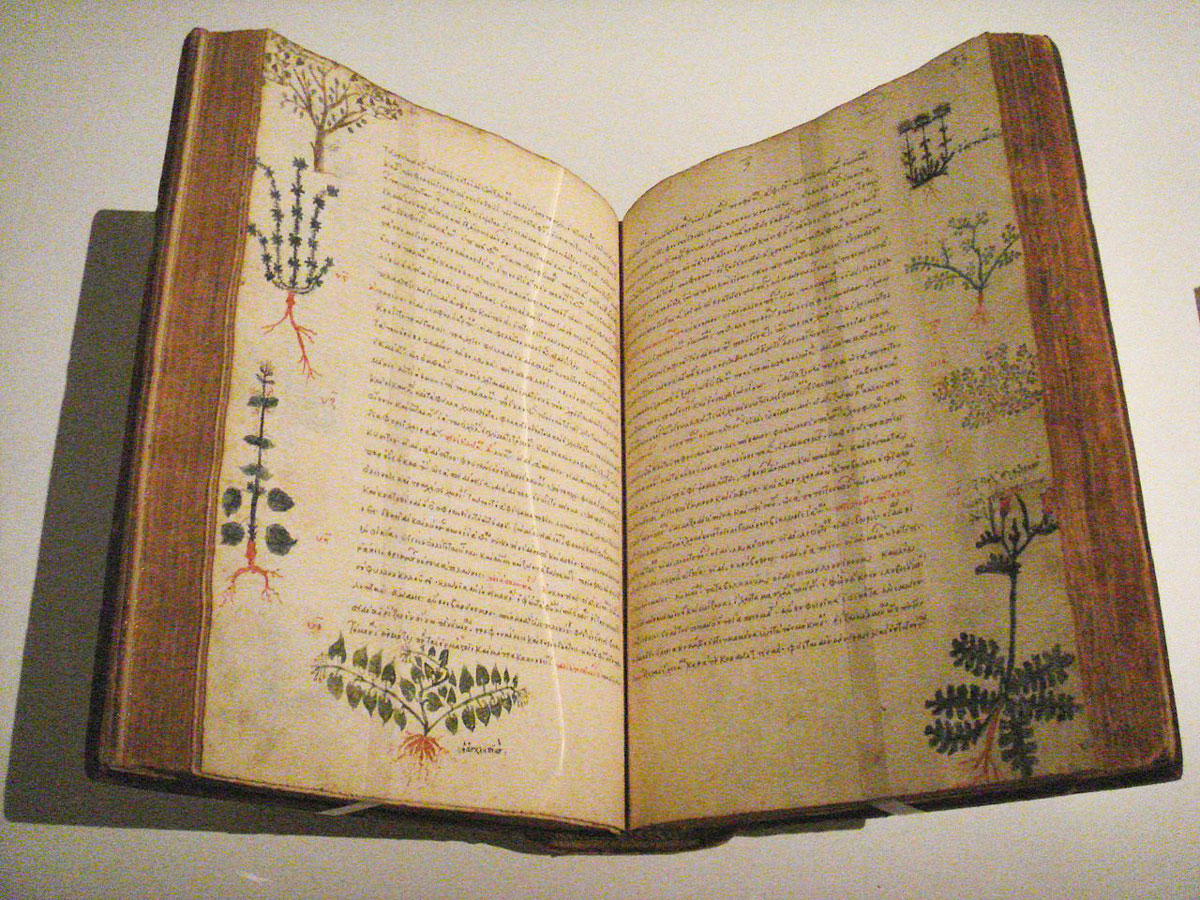

The original manuscript was written almost two thousand years ago and has never been found; however, the oldest known copy, named the “Vienna Dioscorides” or Codex Vindobonensis Medicus Graecus 1 (ca. 512 CE), is currently in the Austrian National Library in Vienna. This special-ordered copy, written in the original Greek and adorned with beautifully hand-painted illustrations, was created as a royal gift for the Roman imperial princess Juliana Anicia, who was a well-known patron of the arts. The manuscript, a “masterpiece of book art,” is registered with the Memory of the World Programme established by UNESCO, which describes the volume as “the most important pharmaceutical source of the Ancient World” (UNESCO Memory of the World, n.d.).

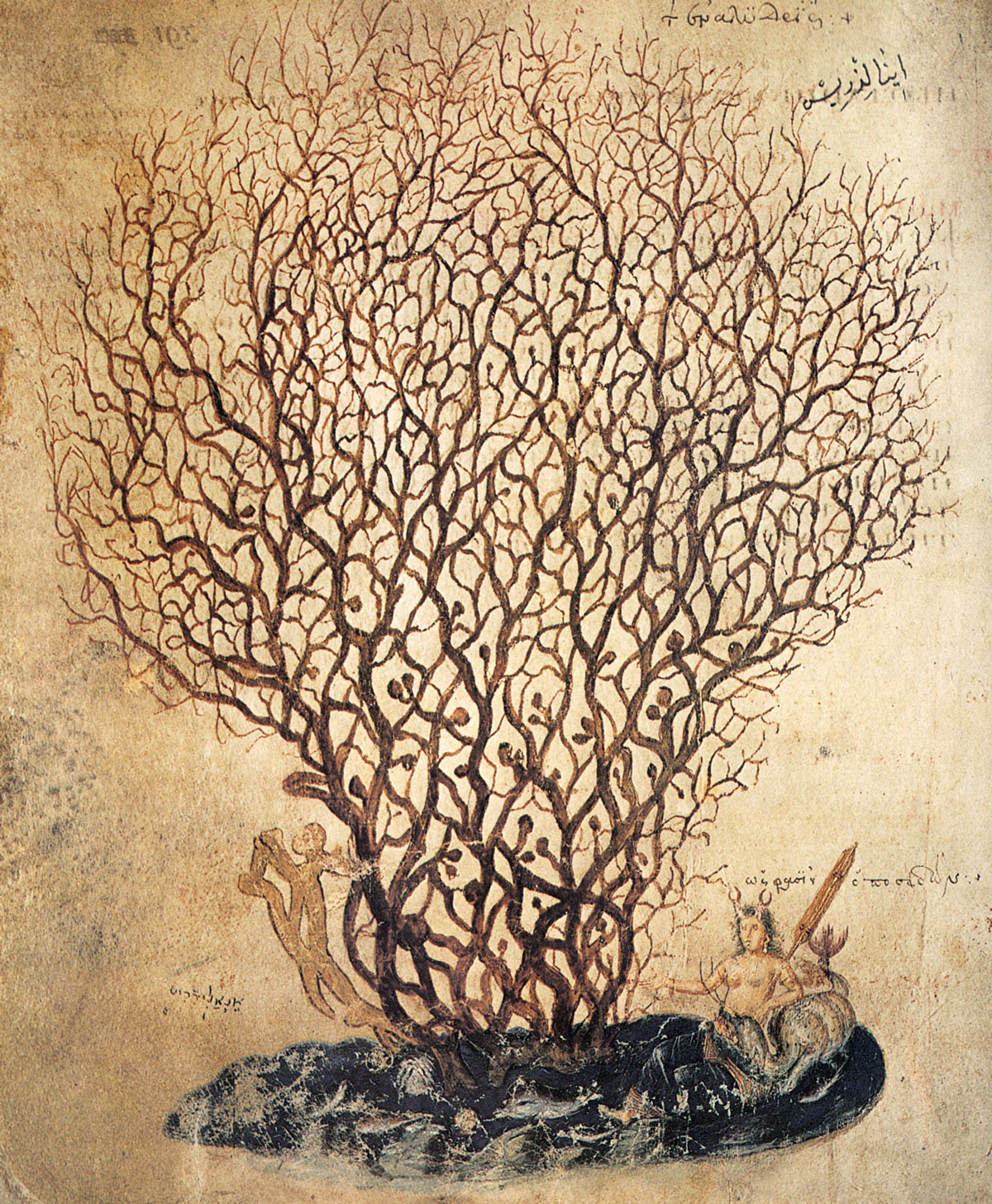

Illustration of coral from the Vienna Dioscurides (Public Domain).

Other celebrated copies can be found in the national libraries of Greece, Spain, Italy, France, and Britain, as well as in the sacred monastery of Mount Athos, Greece, and the Morgan Library and Museum in New York City, obtained from a 1920s auction. Single pages from manuscripts can also be found in many museums, many of which have been digitized and are available to view online, including in the Smithsonian Institution, the Harvard Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Walters Art Museum, among many others.

For English-language readers, the first and only translation from the original Greek to English was surprisingly not completed until 1655. This copy consisted of more than 4,000 pages and took John Goodyer, a distinguished English botanist, roughly 3 years to complete, during which he consulted at least eighteen editions of the manuscript. An edited version of Goodyer’s medieval English translation was completed centuries later, in 1933, by R.T. Gunther, founder of the Oxford Museum of the History of Science (Magdalen College at University of Oxford, 2014). Most recently, a modern English translation from Goodyer’s edition was completed in 2000 by Tess Anne Osbaldeston and R.P. Wood, who created a 1,000-page text complete with vivid images borrowed from well-preserved 16th-century editions (Cilliers & Retief, 2001). This newest publication finally allows modern English readers the ability to access and fully appreciate the breadth and depth of Dioscorides’ outstanding feat. In addition to purchasing it, it is also available for free online.

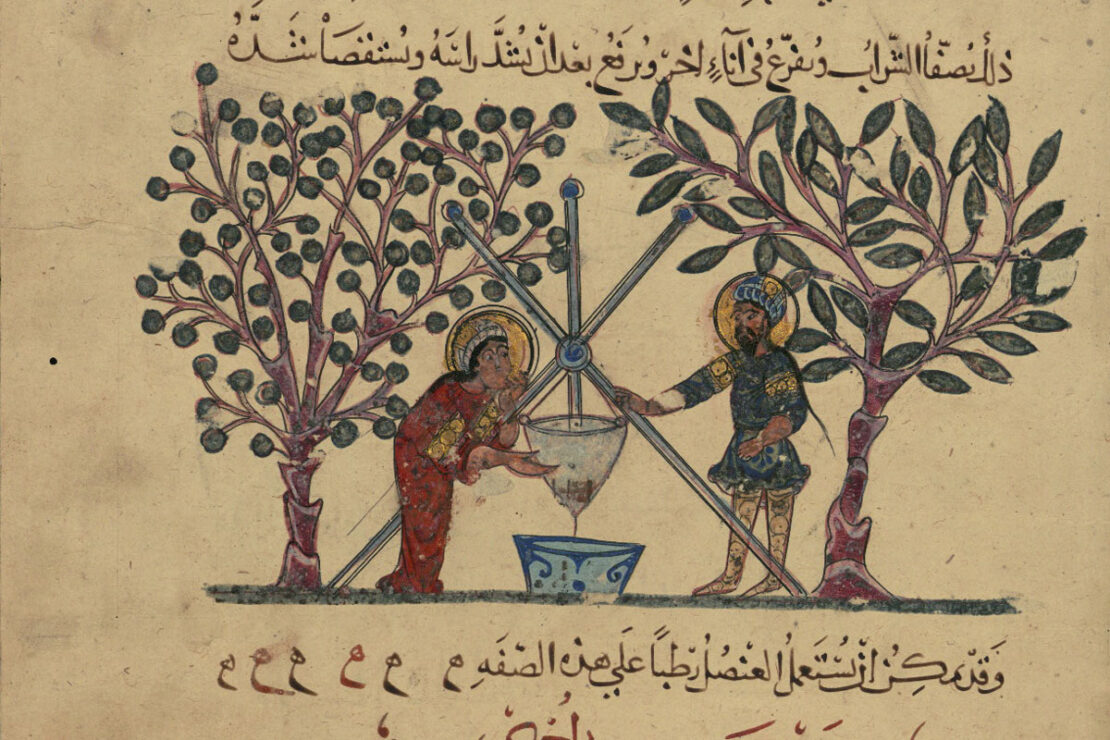

A folio from the De Materia Medica of Dioscorides – 13th Century watercolor on paper. (Metropolitan Museum of Art – Public Domain.)

The Bounty of De Materia Medica

What makes De Materia Medica significant in the history of medicine is how well-referenced it is by medical practitioners and herbalists throughout the centuries and in multiple languages. Undoubtedly, the ancient medical texts from Chinese, ayurvedic, and Arabic traditions also contributed invaluable knowledge. For Western and European herbalism, specifically, De Materia Medica helped educate physicians on natural medicines and elevate the importance of using plants native to Europe and the Mediterranean in a healing capacity. Both the knowledge and the plants had become more accessible than ever before.

Dioscorides documented everything he learned about plants, animals, and minerals from his travels. To organize his information, he divided his book into five parts:

- Volume I: Aromatics

- Volume II: Animals to herbs

- Volume III: Roots, seeds, and herbs

- Volume IV: Roots and herbs

- Volume V: Vines, wines, and minerals

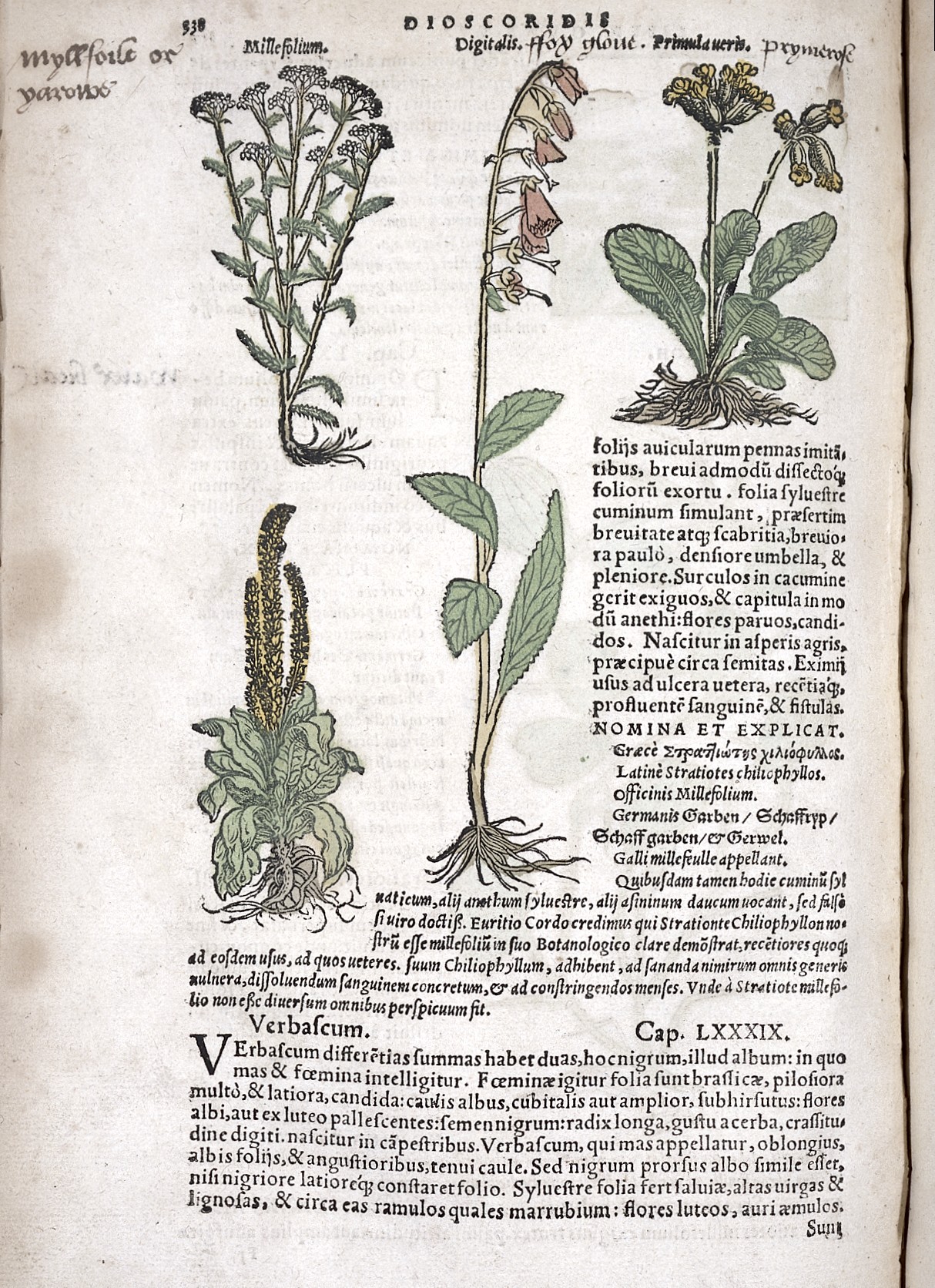

Yarrow, foxglove, and primrose pictured in De Materia Medica. (Credit: Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images images@wellcome.ac.uk http://wellcomeimages.org.)

Each section provides a bounty of information about where the herbs grow, how and what to use them for, and other interesting tidbits that we can use to infer about life in ancient times. From potions using mandrake and hellebore to herbs “effective against things that darken the pupils,” (Dioscorides, Osbaldeston, & Wood, 2000, p. 319) some of these are worth noting only for their unique applications (such as cow dung!) and some remain applicable for use in the Western pharmacopeia. A sampling of information from the 1,000 pages of De Materia Medica translated by Osbaldeston and Wood includes:

Celandine (Greek: Chelidonion mikron, Latin: Chelidonia minor) “grows around waters and marshy places. It is sharp like anemone, ulcerating to the outside of the skin.” Suggested remedies included juicing the roots and inserting “into the nostrils with honey for purging the head. Similarly, a decoction of it gargled with honey powerfully purges the head and purges all things out of the chest” (Dioscorides, Osbaldeston, & Wood, 2000, p. 355).

Fresh cow dung (Greek: Apopatos), when wrapped in leaves and heated above hot ashes, “lessens the inflammation of wounds” and “serves as a warm pack for lessening sciatica.” When “applied with vinegar it dissolves hardness, [goiters], and bone inflammation” (Dioscorides, Osbaldeston, & Wood, 2000, p. 222).

Garlic (Greek: Skorodon), among its many uses, was “rubbed on for loss of hair but for this it must be used with ointment of nard.” It can also be combined “with salt and oil [to] heal erupted pimples.” (Dioscorides, Osbaldeston, & Wood, 2000, p. 319)

Gentian, the “most bitter plant material known,” was named for Gentius, the last king of Illyria who, according to Dioscorides, was first to find it. “A teaspoonful of extracted juice is good for disorders of the sides, falls from heights, hernia, and convulsions. It also helps liver ailments and gastritis taken as a drink with water. The root, especially the juice applied as a suppository, is an abortifacient. It is juiced by being bruised and steeped in water for five days, then afterwards boiled in the water until the roots appear on top. When the water is cold it is strained through a linen cloth, boiled until it becomes like honey in consistency, and stored in a ceramic jar” (Dioscorides, Osbaldeston, & Wood, 2000, p. 367).

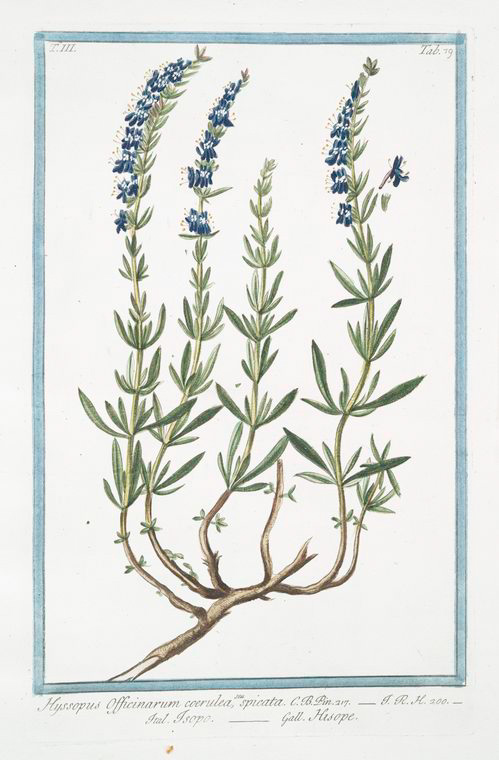

Hyssop (Greek: Ussopos, Latin: Hyssopus hortensis or Hyssopus officinalis or Origanum syriacum) “boiled with figs, water, honey, and rue and taken as a drink it helps pneumonia, asthma, internal coughs, mucus, and orthopnoea [type of asthma], and kills worms” (Dioscorides, Osbaldeston, & Wood, 2000, p. 399).

Licorice (Greek: Glukoriza, meaning “sweet root,” Latin: Glycyrrhiza) helps with “burning of the stomach, disorders in the chest and liver, parasitic skin diseases, and bladder or kidney disorders. Taken with a drink of passum [raisin wine] and melted in the mouth it quenches thirst. Rubbed on, it heals wounds; and chewed, it is good for the stomach” (Dioscorides, Osbaldeston, & Wood, 2000, p. 371).

Wormwood (Greek: Apsinthion, Latin: Absinthium vulgare or Seriphium absinthium, or Artemisia absinthium), which was banned for its narcotic properties in the U.S. until 2007, was well-known in ancient times, with the best kind growing in Pontus and on Mount Taurus in Cappadocia (current-day southern Turkey). “It is warming, astringent, and digestive, and takes away bilious matter sticking in the stomach and bowels” (Dioscorides, Osbaldeston, & Wood, 2000, p. 392).

To this day, there are herbs from the ancient world that we have yet to identify, including Acanthium (Greek: Akanthion), which grew a soft web at its tip, similar to silk, that was gathered and spun. The leaves and roots were prepared as a drink to help alleviate a stiff neck (Dioscorides, Osbaldeston, & Wood, 2000, p. 384).

In Closing,

Fortunately, there are many pages of De Materia Medica to read that can give us insight into our own herbal practice. Additionally, these records continue to provide an exciting and comprehensive resource not only for practitioners interested in the traditional and folk use of plants, but also for botanists, environmentalists, archaeologists, historians, and those whose ancestors wove these practices into their family customs. The beauty of it is that the pages and possibilities are endless.

REFERENCES

Cilliers, L., & Retief, F. (2001). Reviewed work: Dioscorides De Materia Medica by Tessa A. Osbaldeston, R.P. Wood. Acta Classica, 44, 253-257.

Dioscorides, P., Osbaldeston, T. A., & Wood, R. P. (2000). De materia medica: Being an herbal with many other medicinal materials: written in Greek in the first century of the common era: a new indexed version in modern English. Johannesburg: IBIDIS.

Magdalen College at University of Oxford. (2014). The John Goodyer collection of botanical books. [Online article]. Retrieved from https://www.magd.ox.ac.uk/libraries-and-archives/illuminating-magdalen/news/john-goodyer/

UNESCO Memory of the World. (n.d.). Vienna Dioscorides [Online Database]. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/new/en/communication-and-information/memory-of-the-world/register/full-list-of-registered-heritage/registered-heritage-page-9/vienna-dioscurides/