Bee Warm: Wintering Honey Bees

This time of year, I get a lot of questions about wintering honey bees. Most people are under the misconception that bees hibernate, which is simply not true. Honey bees (Apis mellifera) are eusocial insects. Eusocial insects share three characteristics:

A. Cooperative care of their young

B. Overlapping generations

C. Reproductive division of labor

For more cool information about bees, see my article Five Fun and Fascinating Facts About Honey Bees.

So, rather than die off as winter approaches, honey bees cluster around their Queen to keep her warm and fed. The Queen, sensing summer has waned, gradually stops laying eggs in the late fall and winter. Drones are kicked out of the hive to die. The worker bee’s primary objective is to hunker down, keep the queen alive, and ensure the survival of any brood. In the presence of brood, the hive’s internal temperature must remain around 94 degrees. When the external temperature drops below 57 degrees, the bees begin to cluster to provide warmth and ultimately the survival of the hive.

Clustering is not a passive activity but rather a constant vibration of the honey bee’s wings using their arm and leg muscles. This continuous motion is not uniform. The outermost layer of the cluster is the densest point. The inner layer of the cluster allows for the work of the hive to continue, with the workers going about their designated tasks. As you can imagine, all this energy requires calories — calories obtained by the honey stored in the brood chambers. A healthy hive will require about 100-150 pounds of honey to survive the winter.

Honey and natural pollen are the preferred food for bees. The difference in the pH of sugar versus honey may affect the reproductive genetics of the bees long term. Many beekeepers practice natural beekeeping and do not advocate the supplemental feeding of bees with artificial choices.

If my hive has not managed to store the required amount of honey in the hive, I feed the bees a simple syrup solution of 2:1 concentration. Feeding is started in the early fall and continues until the bees either obtain the required amount of honey needed to cluster or once the temperature reaches the point where the syrup freezes and the bees no longer feed on it.

My hives were particularly low on honey stores this year due to the late spring and mild summer, so I have instituted a feeding program this fall.

Hives with low populations will not have the ability to maintain hive temperatures throughout the winter and will probably not survive.

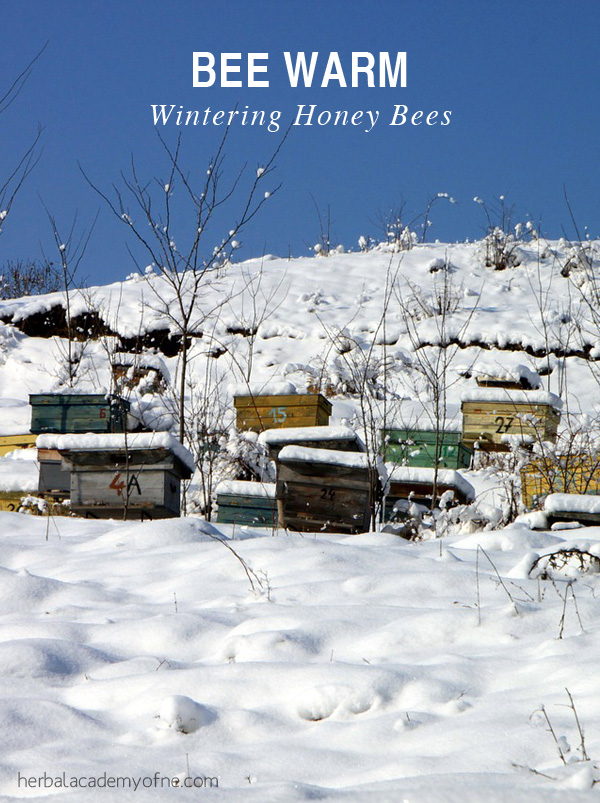

Wind breaks and hive wraps are used in many parts of the country to help honey bees survive the winter. Here in the Midwest, when wintering honey bees, we build wind breaks but do not completely wrap hives due to the volatile temperature changes. Humidity within the hive can lead to the development of disease and kill off a hive quickly. It is a challenge to know when or when not to interfere in the natural cycle of the honey bee. I try to ensure a healthy hive leading up to the winter season, but sometimes, Mother Nature takes a toil despite my best efforts.

I encourage you to plant a variety of pollinator friendly plants and flowers with staggered blooming times to provide a continuous source of natural foraging sources for honey bees.

Flowers like aster, alyssum, borage, calendula, goldenrod, and zinnia bloom late into the fall. Late-blooming herbs like chives, basil, lavender, mint, and oregano are good choices. Dandelions are a primary source of nectar throughout the year. More tips for helping bees.

Remember our pollinators depend on us to make wise choices to ensure their survival, so they, in turn, can ensure ours! Bee-the-Change!

Second photo by Rebecca O’Bea, used with permission for this article.

Rebecca O’Bea is a beekeeper and avid gardener from Kansas. A budding herbalist and student at HANE, she can be found most days knee-deep in compost and blogging about her daily life at The Bee Queen.