The Majestic Honey Bee in Ancient Greece + 3 Recipes with Greek Honey to Try at Home

The majestic honey bee (Apis spp.) has been celebrated for thousands of years by civilizations across the world. In ancient Greece, the honey bee was a symbol of birth, death, and rebirth—transformational themes connected to the mysterious and supernatural realms. As the creator of honey, the first known sweetener in Greek antiquity, the honey bee was highly revered. Honey itself was a symbol of the honey bees’ power to transform the sugary secretions of plants into a delicious substance for human and animal enjoyment. The ancient Greeks incorporated this bee-made sweetness in religious ceremonies, kitchen recipes, and healing remedies.

Evidence of the symbolism of the honey bee and the sacred and practical uses of honey can be found in abundance in the ancient texts and depicted in archaeological discoveries. This plethora of evidence is fascinating to explore for it reveals the ingenuity of the ancient Greeks to transform the image of the honey bee itself from a seemingly simple insect into a sacred creature with divine powers.

We will explore the remarkable history of the honey bee in ancient Greece and learn about delicious honey recipes to try at home. Perhaps learning about and tasting the wisdom of the honey bee can bring eternal sweetness to your own life.

The History of the Honey Bee in Greece

Hold your peace! The beekeepers are at hand to open the house of Artemis.

– Aristophanes, 405 BCE/1995

Symbolism of the Honey Bee

The ancient and modern Greek word for honey bee is mélissa (Greek: μέλισσα). The same term was also used to describe the priestesses, or melissae, who served at the temples of certain goddesses. Demeter, goddess of agriculture and the harvest, was a strong feminine figure in Greek mythology who was connected to both the earthly realm and the underworld. In a tragic myth, her daughter Persephone was abducted by Hades, the god of the underworld who deceived the young woman into living with him and becoming his wife. Persephone subsequently became queen of the underworld and lived there for six months of the year. In response to this arrangement, Demeter grieved for the loss of her daughter during those months and her grief was so profound that the goddess produced no harvest on the land and made those months bleak, thus creating winter.

The honey bee was a symbol of life and death, as reflected in the seasons of the year. Persephone, referred to as the “honied” one, embodied this cycle when she crossed the boundary from the land of the living to the land of the dead (Porphyry, 270/1917, 8.24). Her honey-referenced name was also an indicator of her youthful beauty, as embodied by the season of spring when nature bloomed once again. The melissae were chaste young women who served their mother, the goddess, as a representation of the purity and chastity of this natural cycle.

The melissae also served at the temples of Artemis, goddess of the hunt, the moon, wild animals, nature, vegetation, childbirth, and chastity. The ancient Greeks believed that souls were conceived and brought down from the moon-goddess herself in the form of bees (Ransome, 1937). Temples in honor of Artemis have been found at Ephesus (now in modern-day Turkey) and on the island of Rhodes, where worship for the great mother-goddess attracted worshippers from remote regions in search of healing, culture, and prayer (Kampen, 2003). Male “entertainers” at the temple were called essenes, meaning “king bee” (Seltman, 1952, p. 48). These men were bound to chastity for one year, as a symbol of their devotion to the goddess of chastity.

Archaeological evidence of how the honey bee was affiliated with Artemis indicates a strong sense of worship. Gold plaques were found at her sanctuary on Rhodes and similar ones on Santorini, which depict Artemis with wings and the body of a bee, indicating her role as the bee goddess (Ransome, 1937). At her temple in Ephesus, rosettes with depictions of headless bees were found, indicating that they may have been an amulet for worship and possibly used as a talisman for averting evil (Ransome, 1937). Coins found at Ephesus depicted bees and date palms, both sources of sweetness prevalent throughout the region, and carvings on marble statues, gold pins, plaques, and ritual tokens all had the motif of the honey bee, some dating as early as ca. 700 BCE (Seltman, 1952; Dashu, 2009).

The honey bee, to the ancient Greeks, encompassed a symbol of duality: of life and death, as demonstrated by the worship to Demeter, and a symbol of purity and regeneration, as associated with the chastity goddess, Artemis. Honey bees lived in the mountainsides of Greece—in rock crevices and caves, which were thought to be entrances to the underworld. As a symbol of the dead, honey bees represented the souls of the deceased, and the incarnation of the deceased into a honey bee was described as “bee-souls” (Ransome, 1937, p. 106). A swarm of honey bees was likened to both the gathering and dispersing of souls, as if the new souls and newly deceased entered and exited the earthly realm in this way. These ideas did not escape the minds of those writing about how to lead a virtuous life. The philosopher Plato is said to have believed that “the souls of quiet and sober men came to life as bees and ants” (Ransome, 1937, p. 77).

Bees also held prophetic powers. Well-known ancient philosophers, including Aristotle, Vergil, and Pliny, described bees as weather prophets and relied upon them to predict rain (Ransome, 1937). During times of drought, honey was offered to the goddesses, and prayers were sung to invoke the power of the bee and of the skies to produce much-needed rain.

Honey in Religion, Food, and Medicine

In swarms while wandering, from the dead,

A humming sound is heard. – Porphyry, 270/1917, 7.23

While the honey bee served as a sacred symbol of powerful goddesses and the theme of transformation, honey played a central role in sacred rituals surrounding food, and in medicine. In Greek, honey is called méli (Greek: μέλι), which is the root of the Greek word for honey bee (mentioned above). Honey was considered the nectar of the gods and in sacred contexts, honey represented the sweetness and pleasures of life. It was believed that the sweetness of honey was what attracted souls to be born so that they could experience the delights of being mortal.

This same sweetness helped the deceased descend into the underworld. A libation of honey, paired with milk, oil, and/or water, was offered to the chthonian gods, those relating to the underworld, and to the newly deceased, a practice that continued for thousands of years up until the 2nd century CE. A noteworthy example is during the funeral of Patrocles, a beloved friend of Achilles, the great warrior of the Trojan War. Jugs of honey and olive oil were burned alongside his body. The belief was that by burning the foods he enjoyed during life, he could also enjoy them in the afterlife (Ransome, 1937). And those who led a righteous life would return to heaven, just as the bee returned to the hive: “all souls … who will live in it justly and who, after having performed such things as are acceptable to the Gods, will again return (to their kindred stars)” (Porphyry, 270/1917, 8.24).

Honey was a common ingredient in food and especially in beverages. Before the production of wine, mead was the beverage of choice, still made today by fermenting honey mixed with water (Ransome, 1937). For breakfast, fried dough was made with wheat flour, olive oil, milk, and honey, while for dessert, honey was drizzled on cheese, figs, or olives. During the highly secretive Eleusinian Mysteries to honor Demeter, a drink called kykeon was made by blending honey with barley, mint, or pennyroyal.

Honey was also a very useful medicine and there are many primary sources of medical texts from ancient Greece, Rome, Egypt, and Persia that describe its healing powers. Honey was used both topically and internally for wounds, burns, menstrual complications, digestive complaints, respiratory issues, and even bites of venomous creatures. Honey’s efficacy in soothing wounds and burns, in particular, was noted historically and has been confirmed by modern scientific studies as well (Wallner et al., 2020). In his five-volume textbook De Materia Medica, Dioscorides uses honey, mixed with pine pitch (Pinus spp.) and raisins, as the treatment of choice for infected boils, malignant skin tumors, and “rotten ulcers with scars” (2000, 97), while iris (Iris germanica) chewed and blended with honey can “fill up bare bones with flesh” (2000, 1). Modern science confirms honey’s antibacterial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and regenerative properties. Studies have identified the phytoconstituents of glucose oxidase, methylglyoxal, and bee defensin-1 to be helpful in accelerating healing and reducing infections on burns(Wallner et al., 2020).

It was not without the dedicated work of beekeepers that a steady supply of honey was made available for the population. Beekeeping was a serious profession in ancient Greece and during the reign of Solon (c. 639-599 BCE), strict rules were enacted to enforce a distance of at least 300 feet between each hive. This helped prevent new beekeepers from taking advantage of existing honey-flower locations already claimed by someone else. In Athens, beekeepers vied for a fragrant spot for their hives on nearby Mount Hymettus, where the scent of thyme (Thymus spp.) wafted through the air and attracted the honey bees to make the most favorable honey of the region (Ransome, 1937). In modern Greece, beekeeping continues to be a popular profession and dedicated hobby, and the same desire for access to fragrant mountainsides covered in wild thyme, pine, heather, fir, chestnut, and citrus—endures.

Recipes with Greek Honey

… Also ask for Attic Honey, the feast’s crowning dish—

For that it is which makes a banquet noble. – Athenaeus, 180 BCE/1854, 3.59

There are countless recipes with honey to explore, ranging from the dessert table to the herbal cabinet. Below are a few sweet examples to try at home, each providing the opportunity to savor the ancient goodness gifted by the sacred honey bee.

Kykeon (ancient Greek: κυκεών, kykeȏn)

Kykeon

Meaning “to stir,” this was a sacred beverage of ancient Greece enjoyed during the Eleusinian Mysteries in honor of Demeter. This modern version is adapted from Tokev (n.d.).

½ cup spelt flour

Water

1 ½ cups ricotta cheese

1 egg, beaten

¼ tsp cinnamon (Cinnamomum spp.)

2 ½ tablespoons Greek honey (or local honey)

1 tbsp fresh lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) aerial parts, roughly chopped

1 sprig of fresh lemon balm

Oxymel (ancient Greek: ὀξύς ‘acid’, and μέλι ‘honey’)

Oxymel

“You will find the drink, called oxymel, often very useful in these complaints, for it promotes expectoration and freedom of breathing.” – Hippocrates, 400 BCE/1886, 16

This blend of vinegar, honey, and herbs has been described as “an intangible cultural heritage of Western and near Asian civilizations,” including those in Greece, Egypt, and Persia (Orhan et al, 2022, 3). This is a must-have for your herbal toolkit. There are many ways in which to prepare an oxymel, but the main formula is equal parts vinegar and honey with selected herbs. Hippocrates goes into much detail on the healing properties of an oxymel for a variety of ailments. Today, it is useful as a daily tonic in the winter or in higher doses during illness. Here is a recipe adapted from the Herbal Academy (2018) and Mountain Rose Herbs (2020).

Dried herbs of choice, such as: elderberries (Sambucus nigra), rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus), thyme (Thymus vulgaris), ginger (Zingiber officinale), cinnamon (Cinnamomum verum), cloves (Syzygium aromaticum), and/or rosehips (Rosa canina)

1 part apple cider vinegar, preferably organic

1 part raw Greek honey (or local honey)

To Use:

Use as often as necessary for up to 6 months.

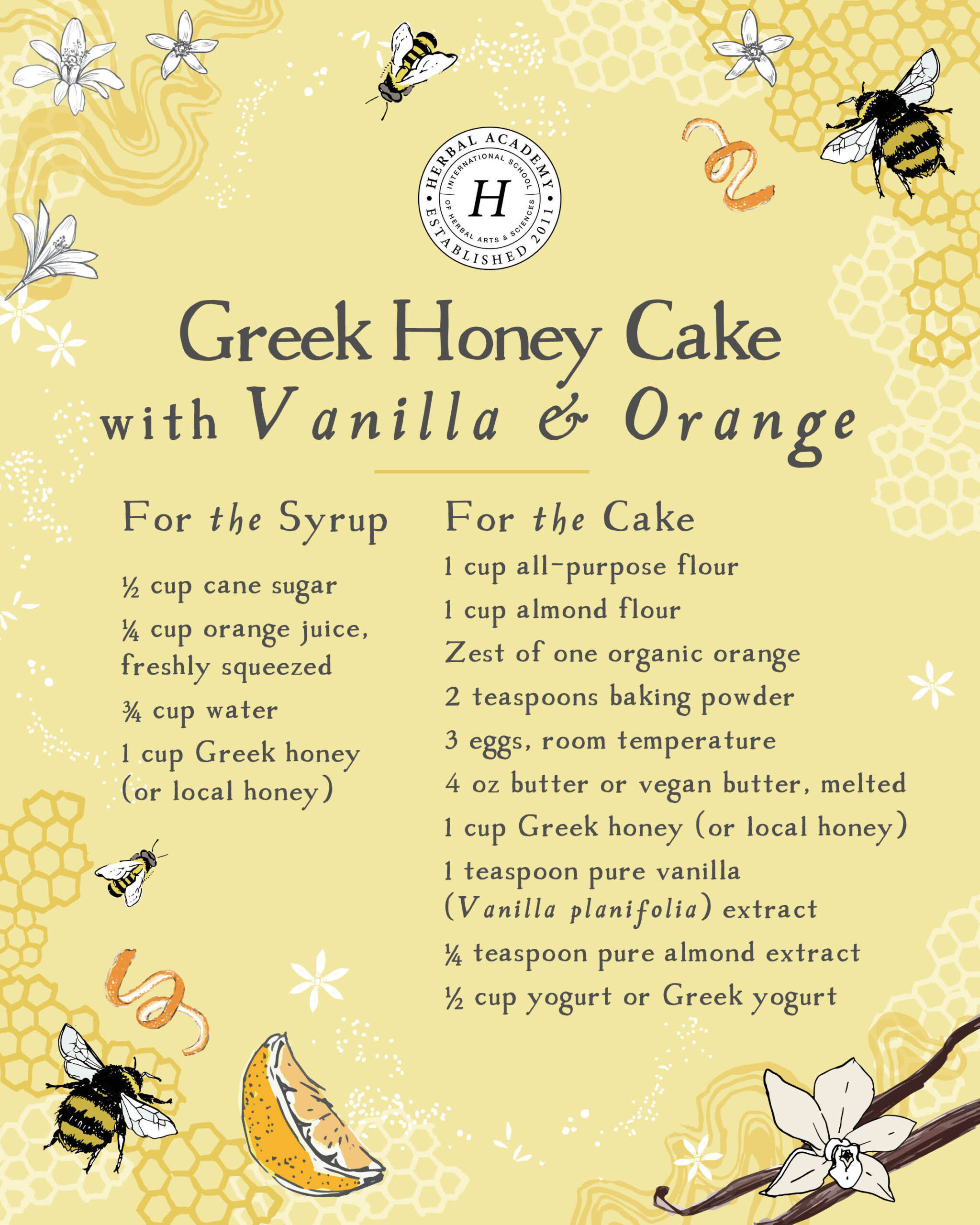

The ancient Greeks used honey-cakes as a special feature in many prayers, festivals, and sacred rites. For personal prayer, a worshipper would visit a cave where snakes lived and offer them a honey-cake for goodwill towards the gods. Honey-cakes were also a feature of the Thesmophoria, an annual fall festival for women. The ancient Greek version was called enkhytoi and was a flat, molded cake made from honey, fine flour, and eggs (Athenaeus, 180 BCE/1854). This modern version is adapted from Dimitra’s Dishes (2022) and is a delightful cake to enjoy for special occasions.

For the syrup For the cake

1 cup all-purpose flour To Use:

Transfer the cake to a serving platter and serve topped with ice cream or with homemade whipped cream. Enjoy!

The honey bee in ancient Greece was a sacred symbol known for its powers to connect humans with mythological goddesses associated with the earthly and underworld realms. The honeybee was also a divine embodiment of the transformations experienced during a human lifetime. Honey bees produced a delight that we can still enjoy today in our food and herbal preparations. These gifts from a humble insect are as honey-sweet as ever and can remind us of the challenges we experience in life—and how honey can help sweeten the way.

For more reading on the amazing honey bee, see: Aristophanes. (1995). Frogs. (M. Dillon, Trans.) Perseus Digital Library. (Original work published 405 BCE)

Athenaeus. (1854). The deipnosophists. (C.D. Yonge, Trans.) London: Henry G. Bohn. (Original work published 180 BCE)

Dimitra’s Dishes. (2022). Greek honey cake. https://www.dimitrasdishes.com/greek-honey-cake/

Dashu, M. (2009). The pythias and other oracular women. Retrieved from https://www.suppressedhistories.net/secrethistory/Pythia.pdf

Dioscorides, P., Osbaldeston, T. A., & Wood, R. P. (2000). De materia medica: Being an herbal with many other medicinal materials: Written in Greek in the first century of the common era: A new indexed version in modern English. IBIDIS.

Hippocrates. (400 B.C.E.). On regimen in acute diseases. (F. Adams, Trans.) . Classics.mit.edu. http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/acutedis.16.16.html

Kampen, J. (2003). The cult of Artemis and the essenes in Syro-Palestine. Dead Sea Discoveries, 10(2), 205–220. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4193273

Mountain Rose Herbs. (2020, March 15). Herbal oxymel recipes & benefits. Mountain Rose Herbs. https://blog.mountainroseherbs.com/herbal-oxymels

Orhan, H., Yılmaz, İ., & Tekiner, İ.H. (2022). Maulana and sekanjabin (oxymel): A ceremonial relationship with gastronomic and health perspectives. Journal of Ethnic Food, 9, 12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-022-00127-6

Porphyry. (1917). On the cave of the nymphs. (T. Taylor, Trans.) London, England: Neill and Co. LTD. (Original work published ca. 270 AD). Retrieved from https://www.tertullian.org/fathers/porphyry_cave_of_nymphs_02_translation.htm

Ransome, H. (1937). The sacred bee in ancient times and folklore. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications.

Saba, H. (2018, September 28). How to make an oxymel. Herbal Academy. https://theherbalacademy.com/how-to-make-an-oxymel/

Seltman, C. (1952). The wardrobe of Artemis. The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of the Royal Numismatic Society, 12(42), 33–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42662998

Tokev, A. (n.d.). Kykeon – The ancient smoothie. Chef’s Pencil. https://www.chefspencil.com/recipe/kykeon-the-ancient-smoothie/

Wallner, C., Moormann, E., Lulof, P., Drysch, M., Lehnhardt, M., & Behr, B. (2020). Burn care in the Greek and Roman antiquity. Medicina (Kaunas), 56(12): 657. doi: 10.3390/medicina56120657

Greek Honey Cake

½ cup cane sugar

¼ cup orange juice, freshly squeezed

¾ cup water

1 cup Greek honey (or local honey)

1 cup almond flour

Zest of one organic orange

2 teaspoons baking powder

3 eggs, room temperature

4 oz butter or vegan butter, melted

1 cup Greek honey (or local honey)

1 teaspoon pure vanilla (Vanilla planifolia) extract

¼ teaspoon pure almond extract

½ cup yogurt or Greek yogurt

In Closing,

Bee Propolis: The Honey Bee’s Secret To Hive Health

REFERENCES