Queen Anne’s Lace Part I: Folklore and Identification

Do you ever look at herbs growing around your home or in your local area and think to yourself, “I should really learn more about that plant,” or “I wonder how that herb can be used?” I do it all the time.

There are so many plants right outside our front door that can be useful to us, but if we don’t take the time to pay attention to them, learn about them, and use them, we’ll never know what we’re missing.

This very thing happened to me this year with one plant in particular—one that isn’t used all that much these days except by folk herbalists. Some call her the queen of herbs, which is quite fitting, seeing how she’s named after a queen. Others call her wild carrot due to her edible, carrot-flavored root, and others sometimes refer to her as bird’s nest because, as her flowers age, they curl upward looking like a cupped bird’s nest.

Any ideas about which herb I’m talking about?

If you answered Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota), you’re right!

Queen Anne’s Lace

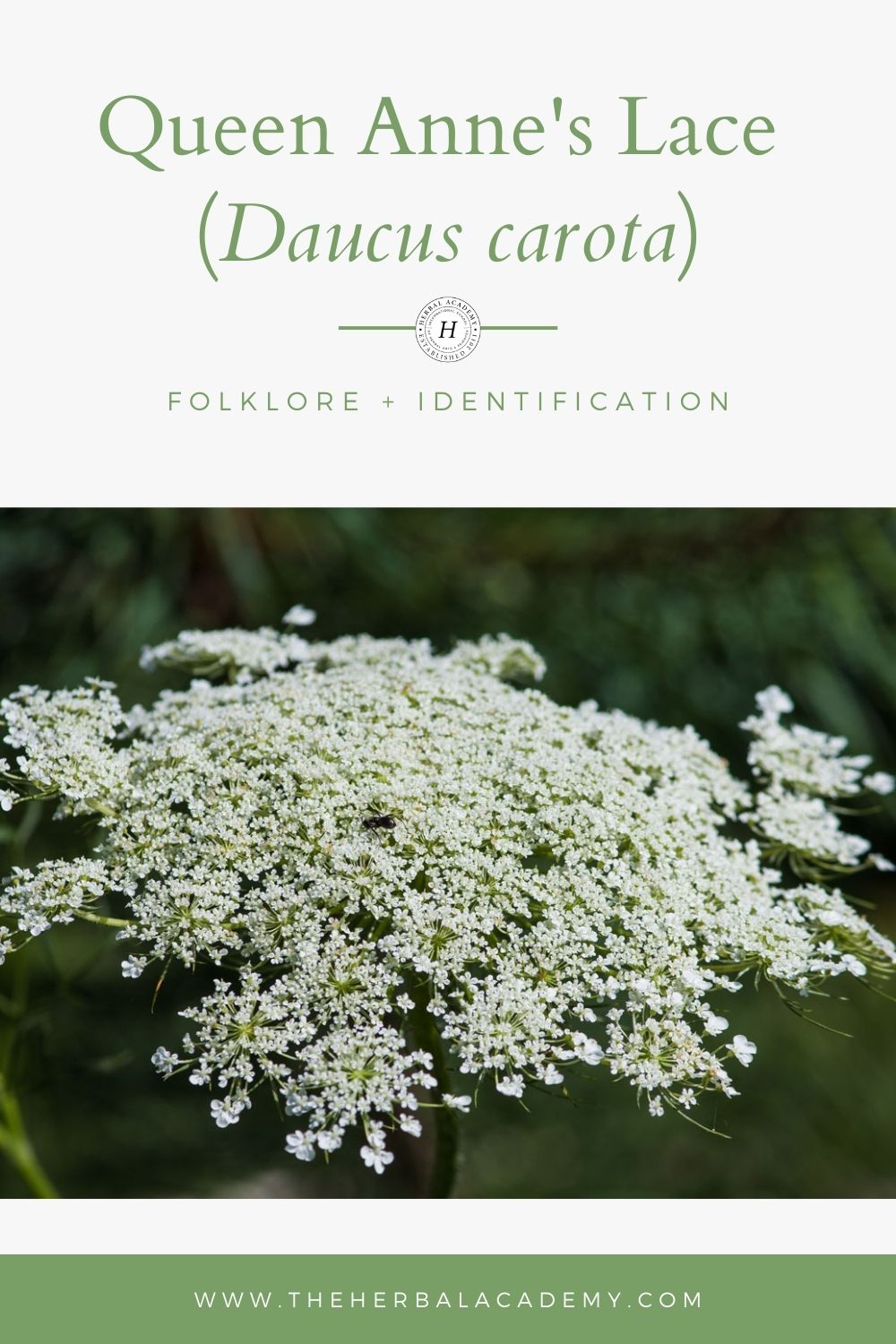

Queen Anne’s lace is quite queen-like.

She has a strong foundation (just try pulling her root out without first loosening the soil)! She has a flexible yet sturdy stem (she doesn’t easily break when strong winds blow), and she is dainty and lady-like at the same time (her delicate flowers say it all).

She is mostly found growing in poor quality soil that is dry, such as roadsides, fields, and disturbed areas.

Her small taproot has a mild carrot flavor and scent, and her branching stem is covered in tiny hairs. Her leaves have a classic fern-like appearance, and her flowers look like delicate lace-like creamy circles that appear in an umbrella shape when young, flattening out as they mature, and eventually forming a bird’s nest shape as they age.

Queen Anne’s lace is a biennial plant, which means in its first year of growth, the root and a rosette of leaves develop. In its second year of growth, its stem will shoot up and produce flowers and seeds.

Queen Anne’s lace leaves are considered toxic due to the presence of furocoumarins (Melough, Cho, & Chun, 2018). This phytochemical can cause allergic contact dermatitis in some individuals when touched, leading to photosensitivity afterward. If you have sensitive skin, it’s wise to wear gloves when harvesting this plant.

Queen Anne’s lace is also commonly used as food. The root of first-year Queen Anne’s lace plants can be harvested and eaten as any other carrot would. They need to be gathered early in the season while they are still tender. The longer they mature, the more fibrous and woody they become. You can also harvest the mature flowers when they lie flat. Simply dip them in a flour batter and fry them as fritters, similarly to dandelion fritters.

Identifying Queen Anne’s Lace

Now, before you go out looking for Queen Anne’s lace, it’s very important that you first become familiar with any look-a-like plants that have similar characteristics to the queen. No one wants to accidentally mistake the queen for someone else, right? That would be disastrous—life-threatening in some cases.

Queen Anne’s Lace Look-alike Plants

Several plants can be easily mistaken for Queen Anne’s lace, such as yarrow (Achillea millefolium), angelica (Angelica spp.), and some of the wild parsley/parsnip plants, but the ones you want to be able to distinguish are the deadly look-alikes, such as poison hemlock (Conium maculatum) and water hemlock (Cicuta spp.).

Poison hemlock is in the same plant family as Queen Anne’s lace, and it has similar looking leaves and flowers. Water hemlock, while also in the same plant family as Queen Anne’s lace, has similar-looking flowers, but the leaves are a bit different. Though both poison hemlock and water hemlock grow much taller than Queen Anne’s lace, small or immature plants can make a wildcrafter hopeful. Yarrow is in a completely different plant family (Asteraceae), but it still has feathery looking leaves and white flowers that are easily mistaken for Queen Anne’s lace. Look at some of these plants side-by-side in the photos below, and you can see why it would be easy for a beginner to mistake one for the other.

Left: Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota), Center: water hemlock (Cicuta spp.), Right: yarrow (Achillea millefolium).

When it comes to correctly identifying each of these plants, herbalist and foraging expert, Colleen Codakas (2018), has written an excellent article about the various ways to spot each of these look-alike plants. She has even included links to external sites that give more detail on the different plants she mentions as well. Learn more in her article, Poison Hemlock: How to Identify & Potential Look-alikes.

So now that you know how important it is to correctly identify this flower from other look-alike plants, let’s talk about a few of the queen’s distinguishing characteristics that will help you properly identify her from other plants.

3 Easy Ways to Identify Queen Anne’s Lace

When it comes to identification, there are some fun little stories you can remember to help you positively identify her in the wild.

First, remember that the queen has hairy legs. Back in the day, ladies didn’t shave their legs, and neither did Queen Anne. This sets her apart from some of her common look-alike herbs with white flowers, namely the two deadly hemlocks (Conium maculatum and Cicuta spp.) and yarrow (Achillea millefolium) as these plants have hairless stems. Speaking of her hairy legs, the queen’s are typically solid green color, whereas the deadly hemlock’s often have purple spotting on them.

Left: Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota), Center: water hemlock (Cicuta spp.), Right: yarrow (Achillea millefolium).

Next, don’t forget that the queen pricked her finger while making lace and left a drop of blood in the center. This is sometimes useful as queen Anne’s lace often has a black-purple colored spot in the very center of the creamy white lacy flowers. While this isn’t true of all of her flowers, you can see this characteristic on some of them.

Lastly, the queen became a bird watcher in her old age. As I mentioned before, older Queen Anne’s lace flowers tend to curl up on themselves, forming a bird’s nest shape. This is another good identifying characteristic of this plant.

If you’ve never identified Queen Anne’s lace in the wild, it’s always a good idea to use a field guide, watch plant walk videos, or take a seasoned forager along with you to help you properly learn how to spot her from other similar looking plants. As I said before, it can be deadly to mistake the queen! Once you learn to properly identify her, though, the differences between her and her look-alikes will be as clear as day and night to you, and you’ll wonder how you ever felt confused about these plants.

Now that you’re more familiar with how to identify this lovely flower, let’s move on to some fun folk stories. As you know, folklore regarding plants are stories, tales, and sayings passed down from generation to generation. Most of these are unsubstantiated, but they are fun to know about nonetheless.

Folklore

Queen Anne’s lace is named after Queen Anne of Denmark, wife to King James I (who is famously known for commissioning the 1611 translation of the Bible for the church of England). It is said that some of the queen’s friends challenged her to create lace as beautiful as a flower, and while doing so, she pricked her finger and left a drop of blood in the center of the lace (Phillips, 2012).

The lacey flowers typically bloom from late May to late August. It is said that Queen Anne often traveled in May, so when Queen Anne’s lace flowers began to appear all along the roadsides, the village people believed the roads had been decorated for her.

Another interesting thought behind Queen Anne’s lace is the symbolism of the plant. The flowers are believed to represent sanctuary. Perhaps this is in part to the umbrella and bird’s nest shapes of the flowers, and it is thought that if you find a forked root, you are lucky indeed!

Queen Anne’s lace seeds are traditionally harvested on the first windy day nearest the full moon after the bird’s nest forms. To do this, collect the flower heads and rub them gently between your hands while outdoors over a white plate. The dark seeds will fall on the plate, and the wind will blow the chaff away (Rago, 2000).

Ancient folklore also says that eating the dark-colored middle flower of Queen Anne’s lace can help reduce the occurrence of epileptic seizures, but there is no known science to back up this assumption.

Lastly, this delicate flower is also known as mother die by some, and according to superstition, if you brought it into your house, your mother would die.

In Closing,

Now that we’ve explored some interesting folklore and learned how to identify this beautiful wild plant, see our post “Queen Anne’s Lace Part II: Traditional and Modern Uses” to learn how this plant has been used for wellness purposes.

REFERENCES

Codekas, C. (2018). Poison hemlock: How to identify & potential look-alikes. [Online Article] Retrieved from https://www.growforagecookferment.com/poison-hemlock/

Melough, M.M., Cho, E., & Chun, O.K. (2018). Furocoumarins: A review of biochemical activities, dietary sources and intake, and potential health risks. Food and Chemical Toxicology, 113, 99-107.

Phillips, S. (2012). An encyclopedia of plants in myth, legend, magic & lore. London: Robert Hale Publishing.

Rago, L.O. (2000). Blackberry cove herbal. Sterling, Virginia: Capital Books, Inc.